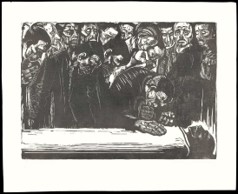

Newly restored Ghent Altarpiece reveals humanoid ‘mystic lamb’

Bettina Baumann | DW | 28th January 2020

Van Eyck’s Ghent altarpiece is hugely famous. Painted in 1432, it is regarded as the first great oil painting and the first significant Renaissance work. Both Napoleon and Hitler tried to steal it. Unexpectedly, restoration has found extensive over-painting. Now cleaned, the original reinforces Van Eyck’s genius – as well as revealing, in the centre panel, a lamb with a human-like face. “We are all shocked” says the restorer.