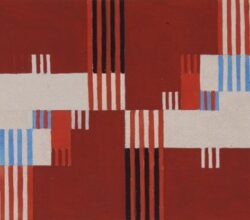

Why textiles are all the rage in the art world right now

Sebastian Smee | Texarkana Gazette | 5th May 2024

Textiles have long been discounted as craft rather than art. Two “fabulous” US shows of textiles indicate this may be changing. One reason is a greater appreciation of textiles’ role in the development of modernism. In addition, current textile artists – like the American Sheila Hicks – are wildly inventive. This writer declares that weaving is “one of the most extraordinary, sophisticated things humans have ever managed to do. It’s connected not just to survival … but also to the human capacity for abstract thought.”