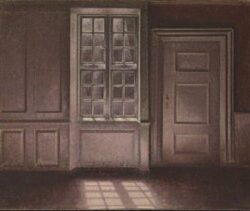

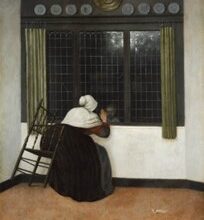

A Dutch mystery: Jacobus Vrel

Irina Diana Calu | Daily Art | 30th May 2023

Who was Jacobus Vrel? All we know is that he was probably Dutch and painted from about 1640 – 1660. His small output focused on humble street scenes and quiet, enigmatic interiors where female figures go about their tasks or just daydream. Sound familiar? Previously thought a mere follower of Vermeer, it turns out that Vrel preceded him by more than a decade. Vermeer, it seems, was not the first to paint “the act of looking”. Wow!