Taste, Figures, Images

Dean Kissick | Spike | 8th June 2022

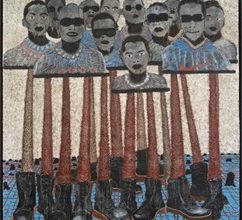

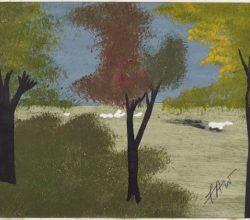

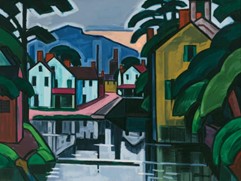

Perhaps this writer was triggered by last month’s speculation-driven art auctions. Whatever, he gradually loses some writerly cool. All art is now experienced on computer screens. Because bad taste no longer exists, “high art” blurs into general image making. And much image making is “pitched against nature, against beauty, aesthetics, against the real.” Rembrandt, he protests, “never painted a raccoon”. If you don’t know what Imagen is, you definitely should read the essay.