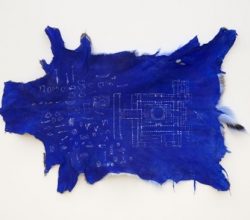

Nicholas Galanin

Aruna D’Souza | 4Columns | 3rd June 2022

Shows of contemporary indigenous art seldom receive such a full size review. Galanin’s multimedia work addresses the survival of traditional indigenous culture in the face of ghastly “assimilation” policies, as well as inappropriate handling of indigenous cultural objects. As befits an artist represented in some major public collections, this show is full of “indelible imagery”. Says the writer, “his art makes me squirm.”