Paula Rego: Yes, With A Growl

There’s a painting entitled Celestina’s House (2000-1). I count at least twenty-two figures in the painting. That’s a rough count. A few of these figures are sitting around a table, presumably eating a meal, though the only food on the table is a lobster and crab, maybe still alive. In front of the table, several figures nap awkwardly on pillows while, nearby, a tiny old woman sits on the floor, reaching up like a baby. Elsewhere, two women work, disconsolate, at a sewing machine, another woman falls down backward through the air, and a young fellow sits on a ladder with his back to us, as if he’s being punished. There is so much going on it is impossible to understand exactly what is going on. It is a scene, perhaps, showing us what would happen if the entire contents of many nights’ dreaming were smashed onto one canvas. The style is more or less realist, but not fastidiously so. We seem to be firmly in the realm of fantasy, memory, fable, and dream.

The artist is Paula Rego. Rego is originally from Portugal (b. 1935) but has lived much of her life in England. Her work has been celebrated in England and to some degree in her native Portugal, but is not as well known elsewhere. She exhibited with the so-called London Group in the 1960s, a group that included David Hockney, Barbara Hepworth, and Frank Auerbach. Recently, The Tate has mounted an exhibit billed as “the UK’s largest and most comprehensive retrospective of Paula Rego’s work to date.” Critical response to the show has been rapturous and widespread. At eighty-six years of age, Rego seems finally to be getting the recognition she deserves.

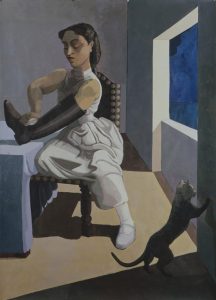

There is quite a lot of Rego’s work to look at, since she has been painting and drawing almost constantly since she was a young woman. Her art is often grouped loosely with Surrealism, though she never belonged formally to that tribe. She has, throughout her career, focused much attention on the strained circumstances of life in Portugal under the authoritarian rule of Salazar, which lasted from 1932 until 1968. Rego’s painting The Policeman’s Daughter (1987) is often referenced as a high-point. The painting depicts a young woman polishing her father’s leather boot next to an open window. The quasi-Modernist landscape of the picture has exactly the uncanny aura that one finds in a De Chirico painting. But here, the unease is more explicitly political. There is something unsettling happening here with power and repression and control.

Paula Rego, The Policeman’s Daughter (1987)

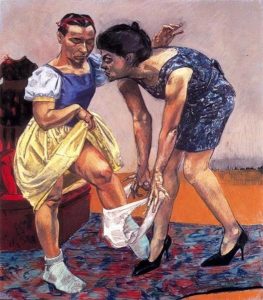

Rego has also created many drawings and paintings that take up fables and fairytales. Some of these are of Portuguese extraction. She has long been fascinated with Alice in Wonderland. A painting from 1995 is titled Snow White and Her Stepmother. In this odd and intriguing painting, a woman in a cocktail dress is helping Snow White remove a pair of white panties. Snow White is rendered as a squat woman with stocky legs and a muscular build (Lila Nunes, a model who has long worked with Rego, and who bears resemblance to Rego herself). The anger and meanness of Snow White’s stepmother takes on a different flavor than in the classic fairytale. The face of our stepmother is screwed tight with what seems to be disgust. Snow White, by contrast, maintains a stolid expression. She is not playing the same game as her stepmother. She is not simply a pretty princess being abused by a jealous stepmother. The painting is probing beneath the surface of the fairytale, beneath the classic story of beauty and competition between women over who will find the desirable mate. And yet, the painting does not reject the idea of beauty. In terms of color and pattern and design it is quite luscious. The lusciousness draws us further inside the painting, where we discover a hard-to-define sexual tension between the two women. The painting explores the beauty and the attraction to be found on surfaces — the surface of a body, the surface of a canvas. But Rego shows us the fraught complexity of beauty, beauty as confounding and creepy, an intermixing of incomprehensible desires and irresolvable feelings.

Paula Rego, Snow White And Her Stepmother (1995)

Rego has spoken frequently about being involved, for many decades, in Jungian psychoanalysis. This isn’t the place to explore the various nuances of the Jungian approach to the psyche. Yet the Jungian background helps us to understand something about the content of Rego’s work. Rego is not an abstract painter. She believes in stories and the way paintings can tell them. Rego often expresses in interviews how she loves both the style and the narrative power of comic strips. And yet, Rego’s paintings do not deliver clear-cut narratives. Her stories are coded in layers of symbol and metaphor. Most of the time, the key to this code is nowhere to be found. Deeper meanings are alluded to but questions are never resolved. Many of Rego’s canvases are thus like snapshots from a long session of analysis. A snapshot, and no more.

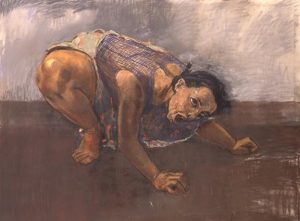

Take, for example, the painting Dog Woman from 1994. A woman in a floral skirt and loose blouse crouches on all fours on the floor. Her right hand practically claws at the ground. Her head is turned up slightly, eyes pointing toward someone above her. Her mouth is open. She is, perhaps, barking. The ground beneath the woman is muddy and brown. The wall behind her is muddy and gray. The feeling-tone here is earthy and sordid. It vaguely resembles a scene from the corner of one of Goya’s Black Paintings. Is this woman mad? Has some event or realization pushed her over the edge and into some kind of bestial regression? There are no clear answers.

Paula Rego, Dog Woman (1994)

There is, though, an interesting line in the painting. It bisects the painting horizontally about a third up the canvas from the bottom, a zone where the brown moves from a lighter to a much darker hue. And that line, I think, is a clue. This painting is not about verticality, not about transcendence. It is about getting down on the ground. It is about mucking around in the dirt like a dog. And to some degree, liking it. That’s to say, there is a lot of power in this dog woman. The horizontal line, I think, emphasizes this power along with the danger of going so low that one cannot return. There is excitement and freedom in allowing oneself to be bestial. Paula Rego once said, “To be bestial is good.” And yet, potential degradation lurks here too. The horizontal line marks a limit. Because to be a person, to be a woman, is not to be a dog. Is it? Or is it?

In 2017, Rego’s son Nick Willing made a unique and quite moving documentary about her (Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories) for the BBC. Rego explains that she painted the dog paintings (there are several depicting human-canine scenarios) as a kind of tribute to her husband, Victor Willing, who died in 1988. These paintings include Bad Dog (1994) a picture that Rego describes as “a woman being kicked out of the bed because she’s pissed the bed.” The woman is on all fours, a slip pulled down to her waist, contorted in the act of crawling down to the floor from a mattress. In another painting Sleeper (1994), one of the dog women sleeps on the floor, her “owner’s” coat lying beneath her legs and lower torso, a dish on the ground just behind. “The dog women are being told what to do by him,” Rego says matter-of-factly in the documentary. It is a disconcerting confession. Rego speaks this truth without any judgement on the matter. She missed Willing terribly after he died and so she made these paintings, paintings in which women behave as dogs. To tidy these paintings with explanations or justifications in order to make them more comfortable would miss the power of Rego’s art. The dog women are miserable and triumphant all at once. They are subservient and powerful. The dog women are unforgettable.

Paula Rego, Bad Dog (1994)

This brings us to another series of important paintings by Paula Rego. It is known as the Abortion series. The paintings were made in response to the failed legal referendum to legalize abortion in Portugal in 1998. It has often been reported that it was partly due to the Abortion series that an abortion referendum was finally passed in Portugal in 2007.

These paintings depict women in the process of getting abortions outside the established medical system. So-called “back alley” abortions. In one of the pictures, a woman lies curled in a semi-fetal position on a makeshift gurney in an otherwise nondescript room. Next to her is a chair. A black plastic bucket sits on the ground. The woman’s feet are tucked into one another as she awaits, presumably, the procedure to come. In another painting, part of a triptych with the previous painting, a woman lies on her back on a surface, perhaps a table, covered in a white cloth. Her legs are spread, though we see her only from the side. The woman grabs her legs just below the knee and has raised her head just enough to turn it in our direction. Her face projects determination.

Paula Rego, Triptych (1998)

It is especially affecting that these paintings are done in pastel. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen pastel used to such devastating emotional impact. Pastel is usually associated with the opposite, with a kind of softness, an indistinct warm glow. But in this case, Rego rips something else entirely from the medium, something direct and unforgiving. The inherent smudginess of the pastel heightens the difficulty, the psychological effort it must have taken to make these paintings. The pastel, by its nature, doesn’t want to do this. But Rego makes it do what she needs it to do. And what she needed these paintings to do was to make a very straightforward political and social point. As Rego put it in an interview with The Guardian in 2019, “[The series] highlights the fear and pain and danger of an illegal abortion, which is what desperate women have always resorted to. It’s very wrong to criminalise women on top of everything else. Making abortions illegal is forcing women to the backstreet solution.”

Indeed, the paintings are so effective at conveying fear and pain that they can be counted amongst a handful of works of art that actually influenced a political outcome, in this case the passing of the referendum making abortion legal in Portugal. But I think it is also fair to say that these paintings are not obviously political propaganda. Political points have a sort of binary clarity at their heart. One is for this and against that. There is an argument and the argument demands a specific result. In this situation, Rego did feel exactly this kind of clarity. She was unambiguously convinced that women should not be faced with a situation where they are getting abortions in such miserable and unsafe conditions. But the paintings are, in fact, shot through with all kinds of ambiguity. Speaking about the Abortion series in the aforementioned documentary, Rego said, “The physical pain and erotic bit are tied. Those girls in the pictures are in a position which could be either for penetration of some kind of abortionist’s hand, or penetration from her lover. … The two things are deeply tied in those pictures.”

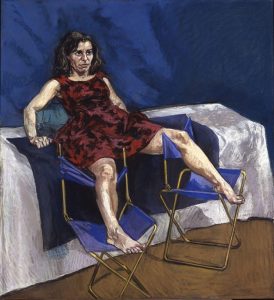

The woman in Untitled 5 from the Abortion Series, for instance, has a slightly amused expression on her face as she props her legs up awkwardly over two collapsible chairs. In another context, she could be involved in something flirtatious, even provocative. Instead, she is about to endure something painful and scary. Still, it is hard to think of this woman as a victim. She has been victimized by circumstances. But she is not reduced by those circumstances. She is fully self-possessed, even as she is abandoning an aspect of herself, even as she is acknowledging, physically, how much her body is under the control of others. There is a defiant ‘fuck you’ in the expression of the woman in this painting, a ‘fuck you’ that, like the growls and howls of the dog women, includes a full acceptance of all that is sordid and dark, as well as the desire that lurks in the crevices of all power differentials. In so frankly portraying the complex layers of desire intertwined in power relations, Rego was able actually to create paintings that helped to shift those relations politically.

Paula Rego, Untitled 5 (1998)

Which brings us back to The Policeman’s Daughter. You could see this painting as a simple allegory of facism. The policeman’s daughter labors during the midnight hour to shine the jackboot of the father. What could be simpler and clearer than that? Except that the painting doesn’t quite seem to play by these rules. It’s the way the daughter twists her face in her labor at the boot. She’s made a fetish of this boot, and in doing so she has also made it, to some degree, her own. She has, in fact, completely penetrated the boot with almost the entirety of her left arm. The sense of order and hierarchy and control that the boot represents in this painting isn’t holding up so well. The folds and ripples and undulations of the daughter’s dress are as much the organizing principle of the painting as the squares and rectangles of the window and the room. And the cat, what of the cat? This is essentially the same cat that can be found lurking in Manet’s Olympia and in countless paintings by Goya. Everyone knows at least one thing about cats. They are not to be controlled. Not completely. It’s never quite clear when it comes to cats who is the owner and who is being owned.

Showing that fascism is bad is one thing. Revealing that the dream of total control at the heart of facism can’t even survive the naughtiness of one cat is quite another. Paula Rego has commented that, after painting a picture about the Portuguese dictator António de Oliveira Salazar called Salazar Vomiting the Homeland, she started to feel sorry for him.

Paula Rego, Annunciation (2002)

An exhibit of Rego’s work at the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art from November 2019 to March 2020 was titled “Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance.” It’s a good title. Most of Rego’s greatest paintings play around in the territory between those two forces. It is a body of work that says yes to life in all its tortured complexity. But this yes is uttered as a growl. It is perhaps no surprise then, that in 2002, Rego did an annunciation painting. It is in the moment of the annunciation, after all, that Mary gets to utter her great affirmation, to say yes to the angel and to declare “be it done to me according to thy word,” even though she has no idea why this is happening to her and never asked for it. In Rego’s painting, the archangel Gabriel appears before Mother Mary on bended knee. Mary sits on a chair in contemporary dress, her short skirt giving us something dangerously close to a crotch shot. Her left foot is turned awkwardly inward. Her right hand twists the stem of a small branch or maybe feather she’s holding in her left. She is not beautiful in any conventional sense of the term. She regards the angel with an almost haughty look. “What in the world could this angel possibly be talking about?”

But there is also, in her gaze, a tentative yes. Why not? Why shouldn’t I be the mother of God? It’s sure to be a strange and wild ride.