Easel Essay Paula Rego: Yes, With A Growl

Morgan Meis | The-Easel | 2nd November 2021

Rego’s paintings tell stories. There are stories of family dramas, real or imagined, stories about the Portuguese dictator Salazar, and about Rego’s flawed husband. This is an artist with a confessed fondness for the easy-to-follow narratives one finds in comics. So, asks Contributing Editor Morgan Meis, what accounts for the pervasive sense of oddness and unease in her work?

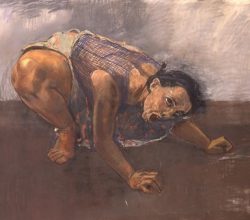

“Her stories are coded in layers of symbol and metaphor. [Dog Woman] is about mucking around in the dirt like a dog. And to some degree, liking it. That’s to say, there is a lot of power in this dog woman. Paula Rego once said, “To be bestial is good.” And yet, potential degradation lurks here too. Because to be a person, to be a woman, is not to be a dog. Is it? Or is it?”