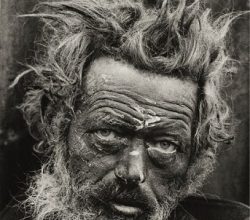

Don McCullin on the stories behind his most personally significant pictures

Don McCullin | AnOther | 5th April 2020

McCullin grew up in grinding poverty, in working class London. That experience influenced his subjects of choice – wars and social injustice – in an acclaimed career in photography. “Photography is like climbing Everest without oxygen and the weight you’re carrying is a moral, mental weight … [You think] God, I’m having such an exciting, wonderful life,’ but if you think it’s free of charge, it’s not. It’s loaded with penalty.”