Introducing: Jean Dubuffet

Camille Houzé | Barbican | 11th May 2021

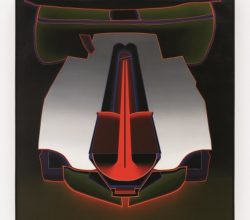

Dubuffet was rebellious, hating academic art theory and rigid art traditions. His aim was to “‘amuse and interest the man in the street”. Child-like figures in his early works, then numerous experiments with “banal” non-traditional materials and, in late career, graffiti-like abstractions. Hockney, Haring and Basquiat are among those to have sung his praises. As for the man in the street, “the success my work has had is quite contrary to the beliefs I hold”.