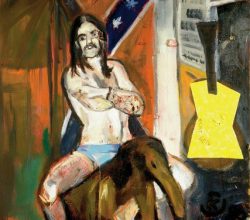

Basquiat: Boom for Real, Barbican review – the myth explored

Sarah Kent | the arts desk | 22nd September 2017

There is some skepticism about Basquiat. Snobbery, racism, envy, the wildness of his art – all perhaps play a role. In addition sky-high prices have meant that very little of his work is viewable in public collections. So what is the verdict on Basquiat’s first London retrospective? High energy art, one critic comments, “wholly fresh … jazzy and garrulous, and surprisingly visually powerful”. An interview with the curator is here.