Antony Gormley: Sculpture is ‘the Most Radical’ of Artforms

Antony Gormley | ArtReview | 27th August 2025

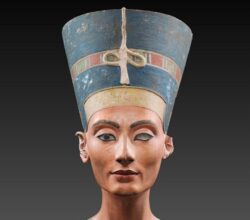

Sculpture doesn’t get nearly the column inches that painting enjoys, something that seems to rankle Gormley. The charisma of masterpieces like the Sphinx of Giza, Nefertiti’s bust, Michelangelo’s David and the Statue of Liberty comes from the inherent qualities of sculpture. It is the most radical of artforms because it “refuses the functional logic that most things in the world obey. [Further], it insists that by changing matter, it changes the world. Sculpture, rather than making a picture of a thing, is the thing.”