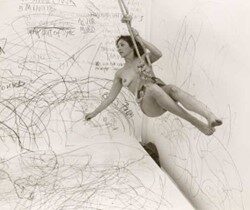

Photography trailblazer William Klein dies at 96

Claire Guillot | Le Monde | 12th September 2022

In 1954, Vogue persuaded Klein that his brash, graphic photography was just what they wanted for their fashion magazine. Shooting fashion out on the street proved influential at the magazine and beyond. More rules were broken with his book of New York street photography that focused on “all the exuberance, violence, and off-beat beauty a city contains”. Published in 1956 – in Paris, not the US – it was instantly acclaimed. Says one critic, Klein was “one of the greatest filmic artists of his age”.