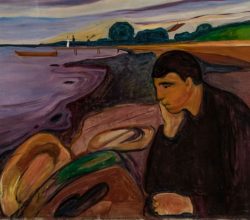

Easel Essay: Goya: Bearing true witness

Morgan Meis | The-Easel | 31st May 2022

Once he was appointed as court painter to Charles IV, Goya knew nothing but worldly success. Yet, over his career, his art became bleaker, culminating in the “Black Paintings” done on the walls of his final house. The usual explanation is that Goya, beset with ill health and appalled by war, became disillusioned. While that is true, says Morgan Meis, there is more.

“Human beings tend to clump together. It just happens. It is born of randomness and yearning, of anger or of dreaming. Goya was interested in this clumping … and perceived clumps and pyramids [everywhere]. In this sense, Goya was never a painter of The Enlightenment. He was a painter of tendencies and forces that are deeper and more fundamental. Clumping was, for Goya, a core truth not to be denied.”