Interiors: hello from the living room

Alfred Mac Adam | The Brooklyn Rail | 1st November 2020

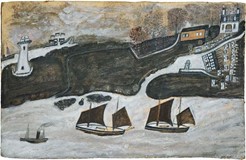

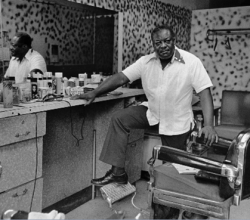

Interiors are a genre with enduring appeal. Images of a simple room with sparse adornments offer “the chaste harmony of geometry “. More often, we get entangled in a painting’s “psychology”. When everything is as it should be, do we infer a sense of security. When things seem a little odd, is it normal messiness or evidence of a crime? And, especially when darkness falls, “looking out or looking in … is charged with voyeurism.” More images are here.