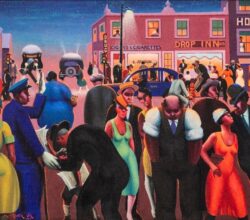

The Met is having a Black moment with the ‘Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism’ show

Ida Harris | Black Enterprise | 25th February 2024

The 1920’s Great Migration brought many Blacks to New York’s Harlem. New ideas about the “new Negro man” encouraged creativity in music and literature – the Harlem Renaissance. The visual arts, however, received scant attention, even though they produced a new “cosmopolitan Black aesthetic”. That aesthetic, says a curator, was a central force in American modernism because it “sought to portray the modern Black subject in a radically modern way.” Background on the Harlem Renaissance is here.