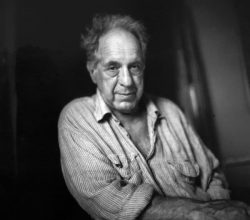

Robert Frank Revealed the Truth of Postwar America

Arthur Lubow | The New York Times | 11th September 2019

Frank was widely regarded as the “most influential living photographer “. The Americans, published in 1958 to mixed reviews, is now celebrated as a masterwork. Its sometimes rough, personally expressive images “shaped the trajectory of 20th-century photography” as well as “embedding “the snapshot aesthetic” into visual culture”. Some of his most renowned images are here.