Bauhaus: A Failed Utopia? (3)

Part 3: Last Rites

This is the last of a three-essay exploration of the history of The Bauhaus in light of the 100 year anniversary of its founding. Previous essays can be found here and here.

In the late 1950s, Marcel Breuer took on a commission to design a church in Minnesota. He was working with the engineer Pier Luigi Nervi. The result of Breuer and Nevi’s efforts is one of the most terrifying structures ever built.

Breuer, born in Hungary, was a charter member of the Bauhaus school. He started as one of the very first students at the school in Weimar. He became a star pupil under the tutelage of Walter Gropius, who made Breuer head of the carpentry shop while he was still a student. Breuer later taught at the Dessau campus. Sometime in 1925 or ‘26, he designed the hugely iconic Wassily chair (known initially as the Model B3 chair, then later renamed after Wassily Kandinsky), a design that came to be almost synonymous with the Bauhaus look, for obvious reasons.

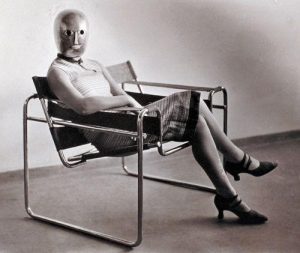

I say ‘obvious reasons’ because the Wassily chair, with its tubular metal construction and sparse look, has all the embrace of domesticated industrial design that so characterized the first decades of Bauhaus. And the damn thing works, somehow. That’s to say, it preserves a sense of comfort and an attention to the human body even in its radical minimalism. If you’ve ever sat in a Wassily Chair, or any half-decent knock-off, you probably enjoyed the experience. There is something playful, something light in the design. The simple twists in the metal tubes make it fun. ‘Fun’ in a startling and challenging way, but fun all the same. This sense of edgy playfulness is captured nicely in the famous photograph of a woman (perhaps Ise Gropius) sitting in a Wassily chair and wearing one of Oskar Schlemmer’s masks.

But looking again at the church in Minnesota that Breuer designed thirty years after the Wassily chair, the words ‘fun’ or ‘playfulness’ do not leap to the lips. Much more apt is the term ‘Brutalism’. This is, indeed, the term that came to be used for much of the monumental international architecture of the late 50s and early 60s. The term ‘Brutalism’ applies to the proposition that whatever challenges a particular building poses, that challenge can be met with concrete.

With respect to concrete, Breuer’s church is quite an interesting experiment. Making an office or apartment complex wholly out of concrete is one thing. But using concrete to make a church strains the limits of what we think of when we think of a church or, for that matter, concrete. Even the most imposing of Europe’s great old cathedrals, with their massive stones and looming towers, are fundamentally committed to decoration, adornment, to creating organic forms out of the blocks of stone. Not so with Breuer’s bell tower. It is a sheet of concrete that pretends to be nothing else. It looks more or less like a giant sidewalk lifted up and placed horizontally across the sky.

And this, to me, is the most interesting aspect of the Bauhaus legacy. Breuer, unlike many of the other students of the early Bauhaus, continued to push at the outer limits of the Bauhaus idea, which was to embrace, and potentially humanize, the new materials and techniques of the industrial revolution. Breuer’s radicalism was necessary since the early efforts by Gropius and others to maintain a balance between craft and industry did not work. Bauhaus lost its way. It was run over by the relentless push for low cost, high efficiency office accomodation. In the aftermath of this failure and attendant crisis of identity, Bauhaus architects and designers created plenty of uninteresting glass and concrete boxes, plenty of designs for kitchen items and furniture that are simply ugly and utilitarian. One branch of Bauhaus lands us at IKEA, which, for all its brilliance as a brand, is simply a watered-down, suburbanized version of the Bauhaus ideal transformed into mass consumer items palatable to all – or perhaps, more accurately, not immediately offensive to anyone.

Marcel Breuer, however, represents another path. Over time, the Breuer wing of Bauhaus got weird and dark. Breuer and other Brutalists made buildings that have the capacity to shake your soul. The stunning aspect of Breuer’s church in Minnesota is that the concrete is so very concrete, so gray, so massive, so unforgiving. It is like a monument to a new and strange God. Confronting Breuer’s church, a person must radically question previous assumptions about what is sacred, beautiful, organic. That’s to say, with Breuer’s wing of the Bauhaus we’re confronted with the proposition that half measures do not ever amount to a full truth. We’re confronted with the proposition that only by concrete fully being concrete will we learn anything about the world within which we actually live, a world of industrial materials and synthetic objects through and through. At the root of many of the buildings Breuer built in the 60s and 70s seems to be the following thought, “don’t fight alienation by resisting it, fight it by going through to the other side.”

There’s a wonderful movie that came out in 2017. It’s called Columbus and was directed by a mysterious man who goes by the name Kogonada. Kogonada was previously known for making thoughtful video essays (which can be seen on YouTube) about various directors and cinematographers and camera techniques throughout film history. Kogonada is, in fact, a fascinating enough subject to warrant a separate discussion the likes of which we don’t have the time or space for here. The interest (for us) of Columbus is that the film takes place in Columbus, Indiana, a small, otherwise-unremarkable town except for the fact that a number of important Modernist architects (Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei, etc.) were commissioned to create dozens of austere monuments to glass and steel and straight lines, from fire stations to elementary schools. The entire town is a secret mecca for super-ambitious High Modern architecture.

But here’s the other thing about the film. It is a film about real people with real problems. It is a film about love and betrayal and desire and disappointment. It is a film about the messiness of human lives in the face of trauma and tragedy. The lives of the characters in Columbus have none of the calm, imposing simplicity of the monuments to Modernist architecture that dominate their town and appear throughout the film.

The genius of the film is to show how the drama of real, complicated human lives is not cancelled out by the formal austerity of the architecture. Something more like the opposite occurs. The formal simplicity of the architectural spaces reveals an openness and generosity. They encourage and allow for the drama and chaos of human life to emerge within, precisely because they are spaces that have not predetermined how a person should think or feel. They are places of a kind of radical clearing, a clearing in which a person is encouraged to ask deep questions: Who am I, really? What do I want? What do I need from others? Of what am I most afraid?

From this, perhaps, we can extract a principle, or at least a rule of thumb. Modernist architecture and design is not meant to be considered in the abstract, for all its abstraction. It is meant to be experienced. And in the experience, surprising things can happen.

In truth, I have no idea what would happen to me inside Marcel Breuer’s great concrete church in Minnesota. I don’t know because I’ve never been inside it, I’ve never sat in the pews. I know about its startling strangeness only from photographs. I did, however, recently visit another church that Breuer built, in Norton Shores, just outside of Muskegon on the western shore of Lake Michigan. The church, opened in the mid-1960s, was constructed according to similar ideas as those that governed the construction of the church in Minnesota. Concrete is the dominant material. When you drive up to the church, making your way through a quiet suburban neighborhood, it is as if you’ve suddenly come upon a government installation for warehousing chemical weapons, or perhaps a bunker left over from paranoid days during WWII when Michiganders dreamed that German U-boats might creep into the waters of the Great Lakes. The concrete cross on the giant, imposing frontal wall is of little comfort and serves, rather, as a kind of warning. Is this some tomb to a long-forgotten tyrant of the Upper Midwest?

And yet, to enter the sanctuary of that church is to enter into a space of awe, the kind of awe that is intimately connected with the religious, the Divine. The space was designed to be vertiginous. Literally, it makes you dizzy. A monumental wall of concrete beams rises up from behind the altar and seems to teeter toward the sanctuary. The concrete beams do not remain stationary as you move about the church. They lean to the left as you move right and vice versa. These are all optical effects, of course. The building is not really leaning and looming. It is not shifting in space and threatening to topple over. It is made of tens of thousands of tons of poured concrete. It is the heaviest building in the world, sunk down into the earth with the weight of a mountain. But the curve of the side walls and the extreme nature of the angles creates a feeling of almost constant, low-level vertigo. This sounds unpleasant. In a sense, it is. But it is also powerful, moving, profound. This is a place in which to confront the central questions: What is God? What does it all mean? This is a place that has truly separated itself from everyday experience, which is, by definition, the nature and purpose of the sacred.

I walked into that church expecting to discover a space that brutally, even cruelly, asserts the incompatibility between Modernity and tradition, between the secularity of contemporary life and the possibility of sacred space. What I found, instead, was a place that had rediscovered, at the extreme end of the weirdest corner of High Modernism, what it means for a church to be a church. And let us be honest. Most churches constructed in the last couple of hundred years have no idea what a church is supposed to look like. So, we get Neo-Gothic and Neo-Medieval. We get churches that look like movie theaters or community centers or, stranger still, a mall. We get cutesy attempts at folksy buildings and all of them, in one way or another, cater primarily to the comfort and coziness of the congregation, as if going to church is supposed to be roughly the same experience as sitting in your living room watching television.

Yet with Breuer’s insane tribute to the power of concrete, we get a church that produces a genuine sense of the awesomeness, the confusion, the fear and the joy by which we confront the idea that there is a world at all, a cosmos, a self. The great mystery beating at the heart of creation. What is it? Who knows? It can’t be known. And yet, there it is.

Who would have thought that the great triumph of the Bauhaus would be to teach us, after so many years, what a church is? Who would have thought that the final steps of Bauhaus inspired architecture would be about worship? That was the last thing I expected to discover in Norton Shores, Michigan. But that is what I found, something ancient and strange at the furthest reaches of concrete.