Lucien Freud: The Self Portraits, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Without a whole lot of anagrammatical labor, “modern master,” which is a term most people in the art game apply to Lucian Freud, becomes “monster made,” which might well describe—to some, anyway—both the artist and his art. Freud might actually like that. Lucian’s Freud’s biography makes bad boy Paul Gauguin—whose life and work I just dove into in these pages—look like a choirboy, a choirboy in a dark religion, admittedly, but still…

Lucian Freud was the grandson of Sigmund Freud, the father of modern psychology and its bastard pop stepchildren: teletherapists and best-selling self-help gurus—hosts of heavily marketed oversimplified interpretations of Freud’s original investigations. Lucian, who is said to have sired somewhere in the neighborhood of forty children, might, in another age, have made an interesting sultan or emperor, a despot who also painted.

In Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud (Sigmund) wrote: “If civilization imposes such great sacrifices not only on man’s sexuality but on his aggressivity, we can understand better why it is hard for him to be happy in that civilization. In fact, primitive man was better off in knowing no restrictions of instinct.” (p. 62) In that battle between civilization and freedom, between superego and id, it’s clear where Lucian Freud falls, though unlike Gauguin, Picasso, and Matisse, who sought the primitive in the indigenous, Freud finds the beast within the confines and traditions of civilized, refined, Western Art.

Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gathers Freud’s myriad gazes at himself. Reflection with Two Children (Self-portrait), 1965, is the one painting you really need to see, epitomizing the exhibition.

“Reflection with Two Children (Self‑portrait),” 1965. Oil on canvas. Collection of Museo Nacional Thyssen‑Bornemisza Madrid. Image ©The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Sleek, mid-century modern, Mad Men in its mastery, Freud, in excellent Don Draper drapery glances down at us from the height of his masculinity, self-satisfied, virile, intimidating and supremely uninterested in us. The two children serve as ballast, balancing the composition every bit as well as a pair of cloisonné vases.

But there’s an entire exhibition around it.

When you look at a roomful of artworks of any successful artist, post, say, 1600 (maybe 1400?) you are looking at the heavy hand of the dealer, the coin purse of the patron, the whisper of the collector, the call of the museum, the shackles of the zeitgeist and the artist’s choice of medium and relationship to it and, at last, the bars of the artist’s inescapable past. By “successful” I mean artists who are known, if not to the general public, then, at least, to the art world, artists who occasionally get an exhibition, are seen at auction, etc.

When you look at a roomful of a successful artist’s self-portraits, you’re looking at a succession of images of ego.

The self-portrait is always an exercise in ego. It assumes that we are keenly interested in the artist, or, perhaps, that the artist’s art is interested in the artist. Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits convey vulnerability. We like that. Lucian Freud’s self-portraits, increasingly as he ages and finds fame and celebrity, convey mastery. They dominate, insist on distance, look down, disdain. We do not like that. And he does not care.

Stand in a roomful of Francis Bacons, or N.C. Wyeths, or Georgia O’Keeffes. Or Lucian Freuds. You will see what I mean. No wonder people turn to folk art, art of the asylum, children’s art. “But is that all there is?” to quote Peggy Lee, or if that is all there is, maybe Arthur Danto is right: meaning precedes making and the artist, who was once a conduit, a vessel for divinity, is, in actuality, merely a conduit or vessel for a tangle of cultural discourses.

The job of the art historian—or critic or reviewer—is to unpack all this and make something of it—some meaning. Structuralists and post-structuralists would say there’s nothing outside—or inside—of these conditions of art. But the truth is, if there is nothing in art that eludes these categories, if all the art you’re looking at does is express some or all of these, it is hardly more than an expression of neurosis. Peter Lorre, famously, was a disciple of Jung before asking Bogart to “Hide me!” in Casablanca. He grew tired of the psychodramas he was tasked to act out with patients, tired, as he put it, of other people’s excrement (he didn’t say excrement). So he performed parody of Hitler that got him on the Fuhrer’s list, fled Vienna, and seemed to have found Hollywood a great improvement.

And so we skip, from discourse to discourse, delighting in the connections we make like fans finding easter eggs in Marvel movies, or, better, like high end art bloggers and columnists, skipping on the skin of the world from fair to fair, gallery to gallery, museum to museum, touting the virtues of artworks that shout their meanings—issues, really—Danto’s vision of meaning preceding making has won, it seems—into a wilderness that is too busy trying to protect itself from human depredation even to take the time to make a show of characteristic indifference—all this while democracy votes itself out of office.

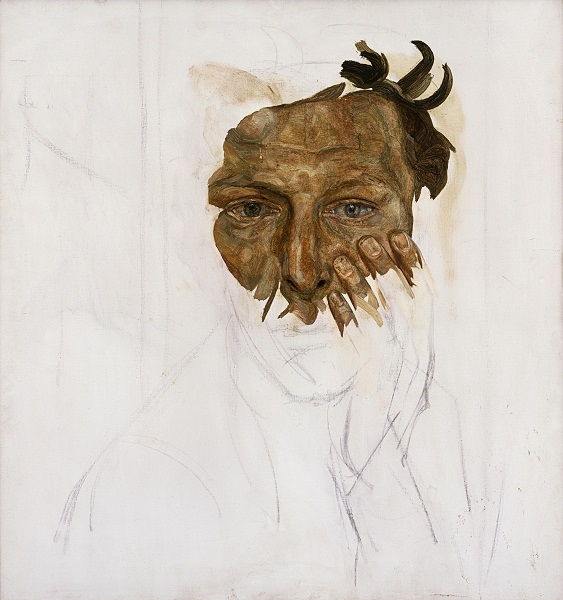

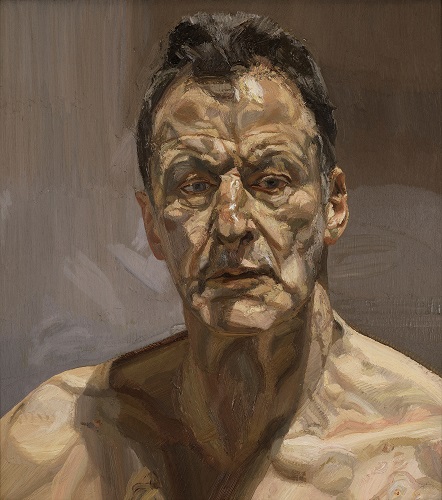

- “Self‑portrait”, circa 1956. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Image ©The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

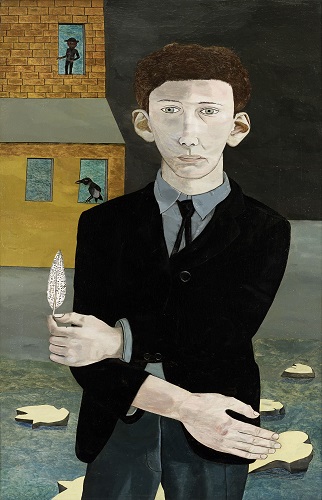

- “Man with a Feather,” 1943. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Image ©The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Adolescent to ubermensch: from the careful, hesitant pen drawing to the large, splashy blobs and claws of brown clay thrown at an otherwise anonymous model, Freud—grandpa Sigmund—would have a field—or do I mean fecal?—day with Lucian’s works.

Lucian Freud’s umbrous navel gazing is a distraction, an opportunity for us armchair Freudians to trot out some pop psychology terms and link up the artist’s bad boy persona with the sequence of his self-portraits. It’s comforting, a blast from the past, Happy Days for aesthetes and aficionados with Freud as Frankenstein’s Fonz. A summation of the inner murmur at the exhibition might go something like this: “Remember when we thought that the psychology of the individual was the last human frontier…? Remember…”

The truth is, the whole affair is sort of fun, as long as you don’t have to interview the artist. Critical distance—distance of any kind—is key. And Lucian Freud wants it that way. Wants us at arm’s length (the better to see you with, my dear).

- “Hotel Bedroom,” 1954. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, gift of the Beaverbrook Foundation. Image ©The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

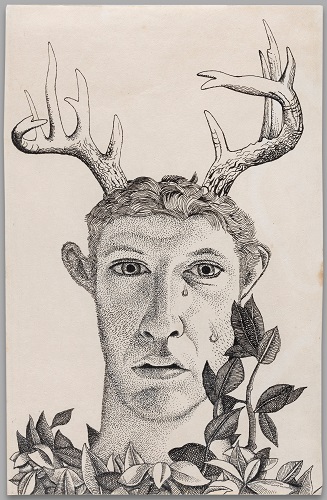

- “Self‑portrait as Actaeon”, 1949. Ink on paper. Private collection. Image ©The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Young Lucian in the 1949 work Self-Portrait as Actaeon is alone and, being the only one wearing antlers to the ball—it isn’t a costume ball—fancies himself misunderstood, looking on and in from the garden, as young Dionysus always does before and after the flesh-devouring frenzy. Or is he just the first one in his boarding school class to sprout horns, the spike buck, honest in his sexuality, exiled because he is out ahead of his peers?

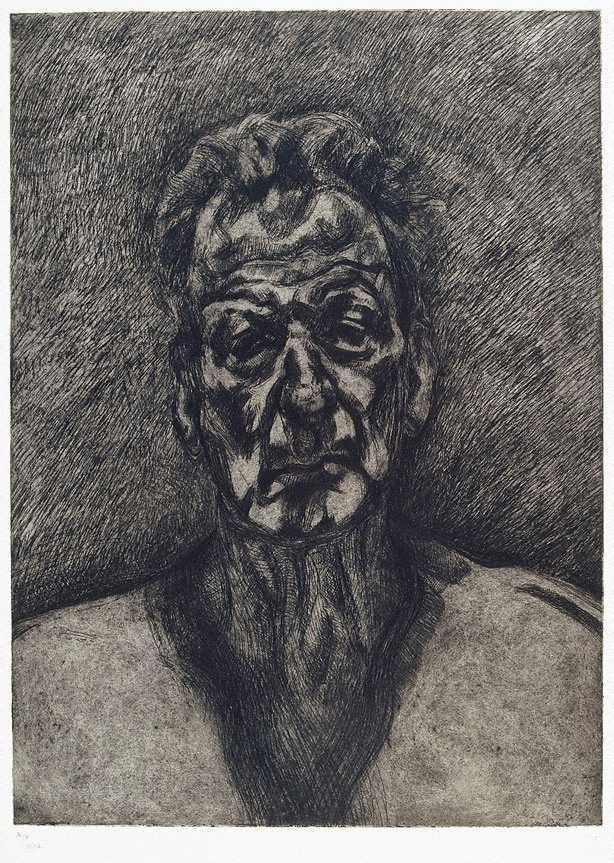

- “Self‑portrait, Reflection,” 1996. Etching print, ink on paper. Artist proof, edition of 46 with 12 artist proofs. Collection of David Dawson. Image ©The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Muse‑ um of Fine Arts, Boston.

- “Self‑portrait, Reflection,” 2002. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Image ©The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images.

Moving from work to work, chronologically, Freud is young and tentative, then virile and invincible. Then, as he ages, he begins to distance himself—from the world, from himself, from his past—watching and judging. Then, at last, in say, Self-Portrait, Reflection, 2002, the mirror stops lying and there is, perhaps, a tinge of regret and forgiveness. Yet the pictures, these songs of innocence and experience, taken together, aren’t anything we haven’t seen—don’t see, won’t see—in our own mirrors. How we live and see ourselves mostly resides in doubt, in regret, in the lashings out—the ones we keep in, that eat us alive from the inside—against fate, circumstance, roads taken and not taken. “What if you knew/you were chosen/not for triumph but for falling short?/What if you knew the wings you wait in/never would open and blot out the stars with their spreading?” the fragment (figment?) whose origins escape me goes but which leads me to another question. When we say that art shows us—or should show us—something essential about the human experience, about human nature, do we mean that it should show us something we know from a gaze and with an economy we had never considered or even thought possible, or do we mean that it should show us some essence, some deeper stuff of life that we didn’t perceive at all? If we mean the first, then Freud succeeds admirably; if we mean the second, I am far less certain. After all, at various points in our lives, as a friend of mine observes, we all look in the mirror and say to ourselves, “You again?” which, in a nutshell, is the reaction Lucian Freud inspires in his self-portraits.

In A Bronx Tale, the gangster asks the kid, “Why do you care so much about the Yankees? They don’t give a fig about you?” (he didn’t say fig). Nor would Freud care what I think about him. In life, collectors lined up to buy his paintings. In legacy, well, one of his recent nudes brought just shy of $30,000,000— at auction. So my words have the force of a gnat around a brown bear. This isn’t surprising. I mean, if Frank Rich’s scathing pan couldn’t keep Cats from running for decades, what chance does any reviewer have?

You get to the end—of the exhibition, the catalogue, the journey—and realize that it’s just possible that how I feel and what I say is exactly what Lucian Freud wants; that he is interested in my (and your) hate, keenly interested in eliciting and probing your hate. Like the Emperor in Star Wars—an analogy he would almost certainly despise—he wants us to release our anger and hate and, through this psychological transference, strip away the trappings of civilization—empathy, in particular— see the ugly, naked truth of human desire, and realize just to what extent we are with him and like him on the feral dark side. Reverse psychology 101.

Freud knows himself. That is something. There’s method in his condescending madness. And he wants us to know ourselves, warts and all, as the old saying goes. But if the people aren’t there to praise or ridicule the emperor’s new clothes because they are too busy trying to pay their bills, raise their children, and save the planet, is the emperor really an emperor at all? In the end, I leapfrog to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Amory Blaine, the protagonist in This Side of Paradise, and to the last line of the novel: “I know myself,” he cried, “but that is all.”

That is all. And it’s not enough.

This essay originally appeared in Antiques and the Arts Weekly. It is being re-published with the kind permission of the author.