Three cheers for ‘irrelevant’ art

Jed Pert in conversation with Morgan Meis

Morgan Meis (MM): Jed, your new book, Authority and Freedom*, has come out in the last few weeks. Congratulations! In it, right near the end, you give this lovely quote from WH Auden, from his poem about Yeats:

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making…

That’s a nice strong quote. Can you saying something about what you think the quote means and how it relates to the argument in your book.

Jed Perl (JP): I’m glad to. These are lines – great lines — that many people know. They were written not long after Yeats died, and they grew out of the tension that Auden felt between Yeats’s art and Yeats’s politics – and, more generally, a tension between what we look for in art and what we look for in the rest of life. Auden in the 1930’s was very much a man of the left. Yeats, who had been a socialist in his younger days, was by the time of his death a man of the right. He was very interested in a quasi-fascist organization, the Blue Shirts, that was having an impact in Yeats’s beloved Ireland. So, for Auden, there was a conflict: he admired the poet but there were things about the man that he found deeply disquieting.

It’s worth remembering that the time when Auden wrote “In Memory of W. B. Yeats” – 1939 – was in many ways very much like ours. The world was in a state of political, social, and economic crisis —people felt the need to take a stand. Out of what Auden saw as a tension between the value of art and the demands of social, political, and economic life came an idea that the poet would insist on over the years. He believed that art lives in the world in its own way. Art doesn’t live outside of life but, as Auden expressed it so beautifully, it “lives in the valley of its making”. He was talking about poetry, but I think this is true of art more generally. He was making an important distinction, which I talk a lot about in the book and which goes back to ancient times, the distinction between making and doing.

To ‘make’ and to ‘do’ can sometimes be used almost synonymously. But many philosophers distinguish between doing – which is something very active in the world – and making, which can be more inward-turning. So, you make a poem, you make music, you are a filmmaker – these people do not immediately go out into the world, but they make things that then have a place in the world. That place is what Auden calls the valley of their making. What Auden concluded was that art has a different relationship to human experience than many other forms of human conduct.

I’ve been thinking about this book for more than a decade. But in the past couple of years, I’ve come to believe that what I have to say has some urgency. Living as we are, in a time of social, political, economic, and environmental crisis, I believe we must resist the temptation to view the arts as a subsidiary or accompaniment to our social, political, and economic experiences and concerns. I believe we have to argue for what I call the freestanding value of art. This is what Auden was thinking about in the 1930’s when he was writing about Yeats.

MM: That’s helpful – the distinction between doing and making. But then, when I’ve made this thing – sculpture, poem, whatever – now it is in the world. And it should do something, shouldn’t it? What does it do then, shouldn’t it do something useful? Looking at this from the perspective of someone who wants to care about art, don’t we have to make that next step and ask what is its purpose?

JP: That is a big question! The relationship between art and the world is messy, I don’t think there is any point in saying otherwise. People have debated aspects of this for centuries. Is the Merchant of Venice an anti-Semitic play? What were Jane Austen’s politics? We care about these things and we especially like creative spirits whose views seem to align with our own. People dislike Picasso for a lot of reasons, not least his complicated relations with women. But we like Picasso because he sided with the forces of democracy in the Spanish Civil War. One of the things we like about George Eliot is that not only was she one of the greatest novelists of the 19th century, she was also a feminist. She was also deeply sympathetic to the Jewish people.

So art and life interact in all kinds of ways. But at the same time, it’s important to understand the different ways we engage with different aspects of experience. One of the questions that has troubled me over the years is exactly the one that you’re asking. If art is at a distance from so many of our social concerns, then why does it matter? My answer to this question – it’s right there in the title of the book – is that in some deep way all artists engage with a fundamental human desire to assert their freedom, their individuality. Every person seeks some measure of individual freedom within the overarching authority of a family, a community, a culture. Creative people are engaged in a parallel effort – to find some individual expression or experience within the more general parameters of a literary, musical, visual, or theatrical art.

Let’s say you’re a painter. What is the first thing you’re confronted with? Most paintings are on a rectangle. They don’t have to be, but the fact is that most are. You’re a novelist or short story writer. A basic fact of the form is that there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. You don’t have to accept those conventions. You can, for instance, write a story with an ambiguous ending – which is a way of asserting your freedom within the storytelling convention. I have come to feel that as we, as viewers, look at a painting or a sculpture, or read a book, or listen to music, we are actually witnessing at a certain remove the extraordinary process the artist has gone through, of taking the given (the authority of a tradition) and transforming it, making it personal.

There are some paintings – some of Jackson Pollock’s, for instance – that explode the rectangle. We react to that explosion as a particular kind of assertion of oneself in relation to a form. The arts are a realm where a lot of experiencing and experimenting goes on. And part of what’s marvelous about them is that it goes on at a remove from our daily experience. Much of what moves us in art has to do with the extent to which things don’t necessarily line up the way they do in many other aspects of our lives.

MM: Putting myself in the mindset of the person who’s more or less willing to go along with what you’re saying, I wonder if they will still have a nagging doubt. They might say, I like to go into a museum or a gallery. I enjoy seeing art, even though I can’t necessarily give you a great explanation as to why I enjoy it. But then I can anticipate a hesitation. If I feel a piece of art is just pure play or experimentation, then it starts to feel empty to me. It doesn’t have a kick.

It might be worth talking about a specific example. The person I’m imagining might ask, for example, why is Picasso’s Guernica such a great painting? We can think about the formal aspects of what Picasso managed to do – in terms of the rectangle, in terms of the pictorial space or the flatness of the surface of the painting, all those sorts of things. However, don’t we all agree that this painting was such a meaningful statement? We all can feel its outrage against war and against fascism. Shouldn’t art do both? Shouldn’t it be doing both things? If it’s not, it’s not doing enough, it’s not doing its job.

JP: Guernica is such a fascinating case. Picasso had accepted the commission to make a mural for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. But for a long time, he didn’t know what he was going to do; his original thought was to produce a mural on the theme of the artist in his studio. Then the Fascists bombed a Basque town, Guernica. The event was widely reported in the papers – there were photographs in the papers showing the devastation – and suddenly Picasso went to work. When the mural was exhibited in the Spanish Pavilion many of the leftists who were involved with the Republican cause in Spain didn’t like Picasso’s painting. They didn’t feel it represented what had actually happened. They found Guernica overly personal and private. And they were right. What Picasso was doing in Guernica was going into his own thought processes, his own iconography, drawing on themes of bullfights and Greek myths and so on and creating a very personal meditation on themes of suffering, death, and human cruelty.

The people who defended the painting in the 1930s argued that its power had everything to do with the indirection of Picasso’s process. He wasn’t illustrating an event; he was making a painting. And when we look at the painting now, more than 80 years later, its power has everything to do with the fact that Picasso took a precipitating event and through the process of making that Auden talks about, he created work with a deep, broad meaning. While some early observers may have found the painting insufficiently “relevant,” it was the indirection of Picasso’s approach that gives the mural its staying power – its deeper relevance.

MM: Let’s say someone is struggling to figure out how to look at Guernica. They may know that this is a great painting – and for them maybe that’s enough. Whether it had a political impact is, to them, not important. How would you suggest looking at Guernica – or talking about it or thinking about it or experiencing it – such that you allow it to be the great work of art first? What does it look like when you look at it that way

JP: Well, the decision to do it in black and white and gray, the austerity of it, I think that’s brilliant. It conveys the idea of the black and white photograph, it gives it a kind of tabloid quality. Picasso probably also realized that if he’d been working in full color he’d have had trouble controlling a work that large. And black, it’s the color of mourning. So, the formal decisions and the ‘meaning’ decisions are welded together, they are one and the same.

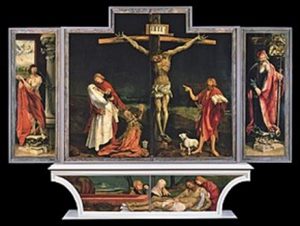

I would say that when you look at a work of art, it doesn’t all come together simultaneously in one moment. There’s a wonderful Meyer Schapiro essay in which this great art historian criticizes the idea of absolute unity in art. He says we actually look at works of art over a period of time and we look at them in different ways. So, in Guernica, you can look at the orchestration of grays and whites and blacks; you can then go through it again and think about the mother holding the dead child. At one moment you may not be thinking about the Spanish Civil War while, at another moment, you will be. The meaning of this work is not locked into the Spanish Civil War. It has become a statement about all war. On another level, Picasso was exploring the idea of the crucifixion. He was not a very religious man, but the idea of the agony, the nightmare of the crucifixion was something he had been thinking about since, some years earlier, he’d studied Grunewald’s great triptych.

MM: Perhaps you are saying that it’s wrong to ask art to intrude into other parts of life – the areas of moral or political questions, even practical questions. It seems to me that you’re saying there is a realm of human experience – you call it a valley a couple of times, using Auden’s line – and to be human is to be able to experience in that way, and art is that place. Since that’s part of being human, it doesn’t need any additional legitimacy, so why do we ask it to be something else?

JP: We ask different things of the various components of our lives. Friendship, for example. We have multiple expectations of friendship – from a casual engagement about work or ideas to something that’s very deep, emotionally sustaining. I think art has many capacities. It can provide idle distraction but also absorb all of our attention. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with wanting art to have a place in the wider social or political world. What does worry me is a tendency to see art’s purpose largely or even exclusively in terms of its social or political relevance. The danger is that we lose track of art’s ability to move us in ways unlike anything else in our experience. “Art’s relevance,” I write at one point in this book, “has everything to do with what many regard as its irrelevance.”

MM: The philosopher Kant put a great deal of effort into considering how humans are situated in the world and how we can know anything about the world or about ourselves. At some point Kant realizes there is a realm that doesn’t fit either the category of understanding or the category of judgment. That realm is where we experience beauty, the sublime, and to deny the existence of that realm is to make yourself, in some way, less human. As we talk, it seems like your argument is coming out of a similar intuition about what it means to take the full richness of human life seriously.

JP: I do believe that the arts are a unique dimension of human experience. But I don’t necessarily think that the arts always tend toward an absolutist experience of the beautiful or the sublime. The arts can also be messy, conflicted – sublimely messy, sublimely conflicted. This brings me back to the idea of authority and freedom. I talk in the book about Michelangelo, especially his later architecture, the Laurentian library in Florence. It’s a very strange structure. Things seem out of whack. The staircase seems too big for the room; the columns don’t really support the ceiling. Some of his contemporaries were up in arms about the building, feeling that Michelangelo was running roughshod over – almost mocking – the ideals of beauty. But I think he was entering into a kind of engagement with ideas of beauty. The end result is that you get a messy beauty, an anticlassical classicism. For me, that kind of ambiguity is part of the richness of the arts. There isn’t just one route. The creative spirit’s struggle between authority and freedom can have many outcomes.

This book began with some lectures I was giving maybe a dozen years ago. My original argument was that art was fundamentally liberal—a negotiation between authority and freedom. When I got down to actually writing, I realized that I, as a person who regards myself as a liberal, wanted art to have that nice liberal label. Some people to the left of me, however, wanted to regard art as radical. And then there were people – I was thinking of the neoconservatives — who wanted to push art in a conservative direction. Ultimately, I realized that all this labeling was a mistake. Art is none of these things. Radical, liberal, conservative – these are terms that come from outside of art. The arts offer an entirely different range of human experience. How can we describe the pleasure of listening to a Mozart piano concerto as radical, liberal, or conservative? It’s none of the above.

MM: The way you’re talking about art implies to me a radicalism, but not a radicalism you can put into political terms or any other terms. It is a kind of radical openness to experience. Something is happening in aesthetic experience – how we look at a work of art or have an experience with music or with a poem – something where our normal sense of our boundaries is getting disrupted. And that’s an aesthetic space where things like that happen, and it’s not something then that fits in very well with, let’s say, political experiences where we actually want to make stronger distinctions.

JP: I think that’s true. I worry – and I know I’m not alone – that all the talk about the political or social significance of art that we’re hearing right now forces works of art into a straightjacket. Are we really seeing the male gaze when we look at painting by Titian? Can this or that painting, or poem be described as Black? Is a work of art gay or feminist? I agree that these kinds of perspectives can take you a certain distance. But the works that have, I would say, real staying power confound such definitions.

MM: I wonder if those delimiting definitions arise at present because people feel the pressures of our times. You could speculate that the area of aesthetics becomes harder to defend because it seems like it’s not as important when other things feel so important. A classic example, perhaps, of what prevails in a contest between the important and the urgent.

JP: You’re right. When you feel like you’re in a state of emergency, art can seem an indulgence, an escape. But that isn’t necessarily the case. During the London Blitz concerts were regularly held in the National Gallery. It had been emptied of art, but Kenneth Clark, the Director of the Gallery, organised these afternoon concerts and people, at some risk to life and limb, would come just to hear somebody play classical music. In those times of extreme duress, the “otherness” of art became very important to people.

MM: Is it possible to acknowledge two things here. First is your point about defending the autonomy of art, defending its weird openness, in order to preserve its potential to make unexpected connections and combinations – all the things that can happen in that space precisely because it is without the boundaries associated with other realms of experience. Separate to that, don’t we also have to acknowledge the difficulties posed by an artistic canon, because that concept potentially reintroduces a lot of political and social and cultural forces. Is there a way to acknowledge both of those things?

JP: Well, I’m glad that you bring up the word canon, because that’s a word that has driven me crazy for years now. The idea of the canon has been lobbed back and forth between the neoconservatives and people on the left. The left says, ‘we have to do away with the canon’ and the conservatives at The New Criterion, where I wrote for a decade, say ‘we have to defend the canon’. Both sides make the canon seem hard and fixed, when we all know that it’s not – it’s not frozen like that. Art is this huge realm where all kinds of stuff goes on.

People get outraged by the idea that art is a system of values that’s imposed on us. What I’m trying to say in Authority and Freedom is that artists who are committed to a vocation engage in a process of making which is a very free process, a very challenging process. Nothing is being imposed on them. An artist’s work has an openness about it because it’s the work of an individual who is open to experience.

Art eludes easy categorization—and the greatest art may elude all categorization. Art can be very extreme. It can be over the top. It can be overwhelming in its ugliness or strangeness. It can shake us up. It can also calm us down. The arts – all of them, visual, musical, literary, theatrical – are a place where we can come together and experience and even understand dimensions of human experience that we wouldn’t have understood otherwise.

MM: If you go back to Kant, he has this basic idea that art is something that we know, we have strong feelings about and yet cannot categorize. We can’t defend them. There’s no proper argument for art, it eludes every category.

JP: And isn’t that very romantic?

MM: Yes, it is.

Authority and Freedom is published by Alfred A. Knopf. It is available on Amazon and elsewhere