The Empathy of John Singer Sargent’s Portraits

John Singer Sargent, Lady Agnew of Lochnaw (1892)

It was often the case in the late 19th century that if you wanted to add a little prestige to your life you had your portrait painted by a notable portrait painter. Or you had your family painted, or just your wife. This latter idea was the thought that occurred to Sir Andrew Agnew, the 9th Baronet of Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. He was proud of his wife, perhaps in the way one is proud of a horse, or an elegant piece of furniture. He wanted others to be proud too. There was a lot of pride going around.

So, Sir Andrew hired a fashionable portrait painter and, in 1892, a portrait was painted. The painting is known today by the name of its sitter, Lady Agnew of Lochnaw. The painter was a Mr. John Singer Sargent.

The portrait shows a person of great wealth and privilege engaged in the act of enjoying that wealth and privilege. To this, we might respond with complete indifference or even hostility. We’re also given, in the portrait, all the trappings of docile femininity. The soft gauzy fabrics of the chair, backdrop, and dress highlight the soft gauziness that adheres to Lady Agnew herself. The painting is staid in every possible meaning of the term.

And yet, I want to say that the painting is also exciting. I’ll admit that the excitement generated by Lady Agnew of Lochnaw is something of an enigma, since there’s nothing especially interesting about a society painting of a long-forgotten aristocrat from a bygone age. It’s a painting for historians to study, or for sociologists to deconstruct, at best. But despite this, despite every attempt to dismiss the painting and all it stands for, there is something that fascinates. The painting seems to rise above its clichés, to brush them aside in the service of something greater. But what, exactly?

There is, for one thing, Lady Agnew’s pose. The Lady is not sitting in her chair the way one might expect. She’s off to the side and almost languishing in the corner of the armchair. This gives the painting a twist and a twirl, formally speaking. That twist affects the mood of the painting and also our own position as viewers. Our gaze is skewed, a subversion of the straight-ahead story we thought we were seeing at first glance. It is strange, really, that we get to see so much of the back of Lady Agnew’s exquisite chair. The painting is as much about unoccupied spaces as it is about the inhabited ones. Or to put it another way, the painting is as much about what isn’t there as what is. As much about what can’t be shown as about what can.

And then there is the gaze of Lady Agnew. What to say about her eyes, especially her left eye, which Sargent has smeared and darkened enough to suggest blemish or bruise? What to say about her raised eyebrow (but is it really raised)? What to say about the right upward tick of her mouth that, when you concentrate on the bottom half of her face, takes on the distinct appearance of a smirk. The suggestion of a smirk? The possibility of a smirk that has not yet quite arrived? And doesn’t she also seem a little sickly, for all her glamour? A distinct torpor weighs this painting down even with all the brightness and light.

John Singer Sargent has painted a straightforward portrait that, the more one looks at it, is crooked all over the place.

+++

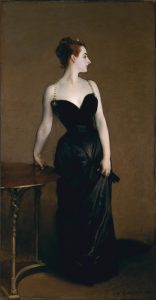

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Madame X (1883-4)

John Singer Sargent was born in Florence, Italy in 1856. He was the child of well-to-do Americans on a Grand Tour of Europe that ended up being permanent. You could say that Sargent was therefore born into expatriatude. He wore it like second skin. He was comfortable in high society no matter what the geographical location. He played a not-bad piano and read the important literature of his time. He studied at the right places and was a star protégé of one of the notable portrait painters of the era, Carolus-Duran, from whom Sargent learned the essentials of the grand style. This served Sargent well in a career that would see him paid quite a lot of money to paint the aristocrats and the super-rich of the Edwardian age.

The one incident that spices this otherwise soporific tale of easy wealth and success is the scandal around what is surely Sargent’s most famous portrait, Portrait of Madame X. There’s no doubt that this is a magnificent portrait. At the time, however, the outright sauciness of the picture caused enough of a huff and puff in Paris that Sargent thought it best to make his way across the Channel. He took London as his headquarters for more or less the rest of his life, with many excursions around and about the continent and long stints spent in Boston and New York. He became one of the most sought-after portrait painters of his, or any, era. In his later years, Sargent was rich enough and exhausted enough to put the portrait-brush down. But he continued to work on other subject matter, producing watercolors, landscapes, and a number of ambitious mural projects, many of which can be found in finer institutions throughout the city of Boston.

Here’s the thing about Sargent, though. Every single one of those society portraits, every one of them, is intriguing. This seems impossible. How could he find something interesting to show us about all these bored and tired and indolent and self-satisfied and listless and pompous and foolish and empty people? How?

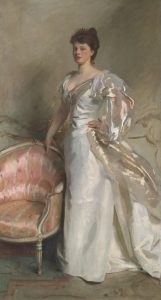

John Singer Sargent, Mrs. George Swinton (Elizabeth Ebsworth) (1897)

Take, for instance, Sargent’s portrait of Mrs. George Swinton (Elizabeth Ebsworth). Sargent painted her in 1897. She seems, from Sargent’s picture, to have been a person who held herself in some esteem. She chose, in getting together an outfit for her big moment, nothing less than a jewel-encrusted tiara, not to mention a dress with puffy iridescent chiffon that flows around her like a regal robe. There’s something so absurd about this portrait one wonders how Sargent was able to go through with it, and, by extension, how he was able to go through with so many of his portraits of the wealthy, powerful, and self-important. Sargent must often have had the desire, as Velazquez did in his famous portraits of Spanish royals, to mock these fools.

But what Sargent did in this portrait instead, as he did in essentially every portrait he ever painted, was to dredge up something from his vast reserve of painterly empathy and put it on the canvas. Neither does he ridicule Mrs. George Swinton nor does he exactly let her get away with it. And this, really, is the secret to all of Sargent’s great portraits. He lets his sitters have it their way, but so much so that the presentation of self begins to collapse. He lets each sitter create their own tragedy, their own farce. He lets them reveal the image they have of themselves, and then he lets that image waver and falter. He runs with the self image and undermines it at the same time. It is a tricky balance, which Sargent gets exactly right almost every time. The end result is not ridicule but compassion.

Let’s look at Mrs. George Swinton again. If young Elizabeth wants to see herself as a great star of the stage, let’s grant her that fantasy. Place the tiara upon your head, dear. Put that swath of glittering sparkling chiffon around your left arm and let it trail out beyond what the frame can hold. The background wall, the chair, the carpet, everything shimmers and twirls and eddies. The back wall could stand on its own as a Turner seascape it’s got so much paint going in so many directions. This painting is having a good time.

But the good time ends at Elizabeth Ebsworth’s face. Comes to a screeching halt, really. Mrs. Swinton is trying to take herself seriously. This is absurd, of course, but also completely understandable. She is trying to be Mrs. George Swinton, and a serious singer (she performed well enough to have sung professionally), and she is also just a young woman trying to make her way in late 19th century society. Read some Henry James and Edith Warton if you’re unfamiliar with the social pressures attendant upon those times.

The brilliance of Sargent’s portrait is contained in the fact that the fun is everywhere but in Elizabeth’s face. Imagine the opposite scenario. Imagine if her face glowed with the lightness and play of the rest of the canvas. That would make this a silly painting of a silly person. But that’s not what we’re given. We’re given instead a painting that contains great tension, elements of tragedy. There is a fierceness and a penetration in the gaze of Mrs. George Swinton. The pink, the tiara, the chiffon are all deadly serious. Elizabeth Ebsworth is engaged in a great battle, a struggle in which her being is at stake, since it is the very ludicrousness of her situation that must be made to work if she is going to continue to be the person that fate has chosen her to be. We are all, of course, living out some version of this predicament, which is why it is impossible simply to laugh at Mrs. George Swinton. She is absurd. But she is admirable. Staring into the eyes of this portrait for a little while makes one thing astoundingly clear: it was difficult to be Elizabeth Ebsworth. A fundamental self-doubt lingers just beneath the surface of her face just as the shadows play beneath the colors of the background wall. Even the slight twist of Elizabeth’s hand on the back of the chair takes on an element of contortion, torment. She’s holding on for dear life.

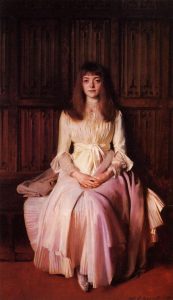

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady in White) (1890)

Another example. In 1889-90 Sargent painted the portrait of a young woman from a rich family in Colorado Springs. Her name was Elsie Palmer. Her portrait is known today as Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady in White). This must have been a very strange and singular young woman. Death obsessed, maybe? Given to long stretches of time spent alone in her room? It is often noted that this portrait seems to capture a person on the cusp. There is a little girl quality to Elsie Palmer, perhaps captured most in her uncertain hands folded at the lap and in her hair, almost frizzy at its lengths and shorn into bangs at the front, which would have read as a pre-pubescent hairstyle at the time. But she is also obviously fully grown. Grown but not necessarily happy about it. Uninterested in being an adult, perhaps a little bit scared. She was, in fact, seventeen years old at the time. She’s a late adolescent, a young adult person. There is upon her face an element of that world-weariness particular to teenagers, a weltschmerz before its time. She knows well enough that entering into adult life is more often than not to enter into what Thoreau called the realm of quiet desperation.

Her look, her gaze — there is so much in it and so little to hold on to. Elsie’s gaze has confused and intrigued viewers since the painting was completed back in 1890. There is, I think, a specific reason for this. The gaze of Miss Elsie Palmer is, in fact, not one gaze, but two. Her left eye looks directly out at the viewer. But her right eye does not. The right eye drifts down and away. Sargent painted Palmer as suffering from a slight strabismus, the technical term for what is sometimes popularly termed ‘wall-eye’.

This strabismus is subtle in the painting but unmistakable when you really concentrate on Miss Palmer’s face. A number of photographs of Elsie Palmer exist from around the time this portrait was painted. The photographs, intriguingly, do not portray anything like the same degree of strabismus that Sargent chose to show in his painting.

So why did Sargent do it? What did he see in Elsie Palmer that caused him to enhance the double aspect of her gaze? It is impossible to say for sure. But doesn’t Miss Palmer, at least as Sargent painted her, seem to be a person of both introspection and outward confrontation? She’s a bit like a ghost, isn’t she, with her layers of white dress and morose countenance? Yet there is a willfulness there too. Morose, maybe, but morose to a purpose. If she is withdrawing from the world, she is withdrawing on her terms.

Notable in the painting is her dress, outmoded by the Edwardian standards of the time. The loose fitting and unstructured fabric harkens back to another age. She sits in a wood-paneled room that could easily be the backdrop in a 16th-century Flemish painting. There is an unworldliness, an otherworldliness, here.

But the left eye confronts the viewer head on. This side of Elsie Palmer is much more firmly situated in the here and now. She takes on the self-assertive, anachronistic attitudes that were not uncommon amongst proponents of the Aesthetic movement in the late 19th century, a movement to which Singer Sargent himself felt some affinity. Think of Whistler and Wilde and Rossetti. This was a movement that chose anachronism as a kind of weapon against the rigors and rigmarole of the industrial age. Elsie’s double gaze is the double gaze of all aesthetes. She is a person who would prefer not to. Sargent’s portrait of Miss Palmer is the creation of a pictorial space where she has the room to do exactly that, to be anachronistic, to fight the seeming inexorability of the supposed progress of history. As to the potential futility of her refusal, Sargent makes no judgement. He simply records.

+++

There is a final point to be made here about Sargent’s style and technique. Sargent’s habitual conservatism as a painter has often been held against him. Impressionism had already made its mark decades before Sargent began his mature pictures. In Sargent’s day, the Post-Impressionists were going even further in non-representational directions and a general rejection of realism. Portrait painting in the grand style was, in the 1890s, looked upon by many of the most forward thinking artists and critics as a kind of crime.

Sargent, though, stuck to his guns. In doing so, he did not become, exactly, a reactionary. He wasn’t simply holding out for the old traditional ways. He was trying to hold a line, a tension, trying to package new wine in old wine bottles, if you will. It was, actually, a brave and dangerous business he was up to. Sargent did learn and master the techniques of the more radical painters of his day. And then he worked those very techniques back into the society portraits and, later, the landscapes and historical pictures of his final years.

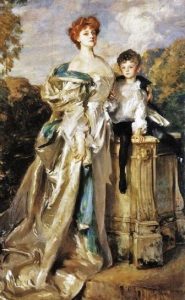

John Singer Sargent, The Countess of Warwick and her Son (1904-5)

Take a portrait like The Countess of Warwick and her Son (1904-5). Here we have another portrait of aristocratic types trying desperately to look upstanding and aristocratic. Literally in this case. The Countess is trying so hard to be a pillar of society that she looks like she’ll crumple at any moment. Her son is not helping much, cocksure and tugging at her pearls. But in typical Sargent style, it is impossible, I think, to hate these people. Their struggle is the struggle of all subjectivity. It is the ludicrousness, the tragi-comedy of putting on the show of being the person that you think you are supposed to be. Sargent’s genius was to reveal the fragility of these moments of person-being without completely dissolving the necessary illusions. Perhaps Countess Warwick loved Sargent’s portrait without ever seeing the desperation in her own face.

But the formal point to be made here is that the painting, as a work of realism, is just as unstable as its subject matter. Look at the shirt on the young boy. The wavy lines look almost finger-painted. The same thing happens up and down the dress of the countess and out into the billowy clouds. There’s even something a bit strange in the morphology of the countess vis-a-vis the pillar base upon which she and her son are posed. Sargent has positioned her so far over the pillar it verges on a defiance of physics. Where, exactly, are her legs? This is not as outright in its bold flaunting of proper perspective as, say, Manet. But that’s the point. Sargent was not Manet. He was trying to incorporate similar formal innovations into a painting that would still be acceptable to the Countess of Warwick. That’s why I call Sargent’s game dangerous. In terms of both content and form, in terms of what you can get away with in pictorial space, he’s always pushing just to the tipping point. And then pulling back. True, he always pulls back. Hate him for that if you like.

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882)

But a painting like, say, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit works precisely because it is a portrait, because it functions within the normal rules of society pictures and the basic realism of the portrait tradition. It is an exciting painting because of how strange it manages to be without completely upsetting the rules and strictures of the form. The emptiness and alienation of this painting is impossible not to feel even if one does not register the feeling consciously. The mysterious darkness out of which these children have emerged. The darkness of the interior of a giant house. The darkness, also, of the not-being from which all beings emerge. The related darkness and mystery of childhood. The darkness, the opacity of being an individual human being at all. Why is one person one person, and another person another person? How stable are these individual identities?

Notice how each of the daughters in the picture is bounded by individual rectangles within the rectangle of the painting’s frame. But each daughter also moves beyond her mini-framing. The littlest girl is on the rug and beyond the rug. The young girl on the left is on the floor and between two wall panels simultaneously. The girls in the back are both in the darkness and in the light. Something, some force of unity, pictorial and otherwise, holds the four girls together. But this same force also keeps them infinitely apart. This is a portrait of specific people, specific young girls of the Boit family. We see them each in their specificity, even the girl furthest removed, turned to the side leaning backward against a large vase, sulking to some degree at the edges of shadow. She reveals herself precisely by her avoidance. We see these young people.

But we also see the problem of personhood writ large. We feel the weirdness of childhood, the strange sense that each little creature is in the process of becoming the full adult consciousness that will one day see itself as the inevitable result of the murk of that childhood. That Sargent was able to dredge these existential moods from the project of a commissioned portrait for a rich family is testimony to the odd pathways by which true art emerges, when it emerges.

John Singer Sargent was not Monet and he certainly was not Van Gogh. He doesn’t fit comfortably into the standard story of painting and its “advances” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He is neither of the avant-garde nor of the conservative reaction. He’s neither here nor there, neither fish nor fowl. Some would consider that an insult. But John Singer Sargent would, I think, have accepted the charge. He was happiest in the ambiguous places between things. His paintings continue to intrigue because that ambiguity is part of the nature of life. It doesn’t go away. It is real. And Sargent found a way to paint it.