Smudgy areas: the art of Berthe Morisot

The painting is known as Woman in Grey Reclining. It was painted in 1879. It depicts a woman in a lovely dress reclining on a couch. Does she have a white flower on the left strap of her dress? Maybe. Probably. We cannot be completely sure. That’s because much of the detail in the painting is only hinted at by the brushwork. A few dabs of white paint here. A few daubs of grey over there. A stroke of black across the neck, giving us the sense of a choker. We’ve come to call this kind of painting impressionist. The term was originally meant as an insult. But it stuck and became a moniker of pride, as often happens with insults.

I’m interested in a very specific part of this painting. It’s an area of paint in the middle right side of the painting (from the viewer’s perspective), the smudgy area of white and grey over the top of the couch just beyond the woman’s arm. Do you see it? What is that smear doing there? It’s not part of the couch. And it’s not part of the woman’s dress. Nor does it belong to the wall. It’s quite disconcerting when you really focus on it. Notice the movement of the brushstrokes. They go more or less up and down, and angle a little bit toward the upper left side of the painting. This is in jarring contrast to the flow of the marks on the dress and the wall behind the couch, which move in the opposite direction. Something grinds to a halt in this area of grey-white smear.

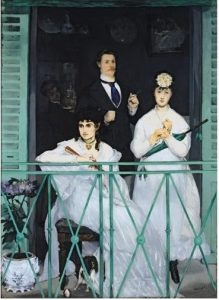

Woman in Grey Reclining was painted, I should mention, by a French woman named Berthe Morisot. Morisot was born in 1841 and died in 1895. She was of a well-to-do family and lived a comfortable life. Nothing much to discuss there. She learned to paint through a private tutor and her work was exhibited at the official yearly Salons in Paris for a number of years until she fell in with the above-mentioned Impressionists in the mid 1870s. From that time until her death she was part of the Impressionist inner circle. She counted Degas and Renoir and Monet and Pissaro among her friends. She was especially close with Édouard Manet, for whom she sat as a model countless times. You’ve seen Morisot, probably without realizing it. She is the surly, dark-haired woman staring intently at something below in Manet’s famous painting The Balcony (1868-9). Morisot and Manet became quite intimate friends, with her sitting for him countless times. In 1874, Morisot married Édouard Manet’s brother Eugène Manet.

Edouard Manet, The Balcony (1968)

For reasons mostly having to do with sexism, Morisot’s work, though highly regarded by many critics and fellow painters, never found its way into the big institutional collections. Most of her paintings are still, today, in private hands. Thus she has, like so many other woman painters, failed to get her due all these years.

That is beginning to change. A huge travelling exhibition entitled Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist took place from 2018-19 with shows at the Barnes Foundation, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie. Critical reception followed suit, with positive reassessments of Morisot’s work in major publications, scholarly journals, and monographs. Morisot is emerging from the shadows and taking the place that her fellow male Impressionist painters had already granted her back in the late nineteenth century, that of a major, first-rate painter in the movement.

—

Getting back to the smudgy area in Woman in Grey Reclining. It’s intriguing because it’s not quite like the smudginess in other Impressionist works. All Impressionist paintings are, of course, a bit smudgy to greater or lesser degrees. I mean, the whole point of Impressionism was to explore the fuzziness of visual experience, the blurring of boundaries that happens with light and color, the way that seeing dissolves and resolves at different distances, both spatially and temporally. Painters like Monet and Pissaro and Renoir — these artists were trying to get away from the painterly tradition they’d inherited in order to see with fresh eyes. If nothing else, they wanted to shake the dust from the tradition. What are we really looking at when we look at a painting, they were asking, and why does it matter? Can a painting give us deep insights into what it is like to experience the world, to be in the world? And might paintings have to jar us a little in our visual experience in order to do that? Those, I think, are the basic underlying questions of the Impressionist tradition.

Berthe Morisot is firmly within that tradition. But she went further than any of the others in some of her blurring, in the smudges like the one we’re talking about in Woman in Grey Reclining. Because the smudge in that painting doesn’t just question the boundary between woman, couch, wall, whatever; it threatens to obliterate the boundary completely. And that word ‘boundary’ is a key word in the paintings of Berthe Morisot, at least the paintings of her artistic maturity, which can be dated from the mid-to-late 1870s until her death in 1895 (though her final period takes a quite interesting, radical turn that we’ll discuss shortly). Morisot was very interested in boundaries, so interested in them that she was willing to play with the painterly possibility that the woman in Woman in Grey Reclining, for instance, might not have very precise boundaries at all. The woman has her own lines. But her lines also merge with the lines of the couch and the wall, and the smudge that is all of those things and none of them. It is as if Morisot was exploring just how ephemeral she could make the physical boundary between this woman on the couch and all the other stuff in the room yet, at the same time, still keep the sense of that boundary. The smudge is just large enough to make an impact on the viewer without being so large as to become the focus of the painting. The result is a picture that seems on the verge of falling apart in the same way that a melodic line in one of the more evanescent compositions by Debussy threatens to evaporate into a tissue of dreamy, disconnected notes that float away into the breeze.

To call this an exploration of visual experience, in the way that other Impressionist works are sometimes discussed, would miss the mark. Visual experience is rarely quite as undefined as this, unless someone just poked you, Three Stooges style, in the eyes. But we can understand, I think, how the experience of being this woman, or being in the room with this woman, might feel blurry in just this way. We can understand the mood that the painting is conveying to us. We can almost get into the specific smell and sounds of some random summer day in which nothing in particular is happening, and a woman is lounging on a couch as various thoughts pass in and out of her mind and the afternoon flits into evening like a dream. Boundaries can fade away on an afternoon like that.

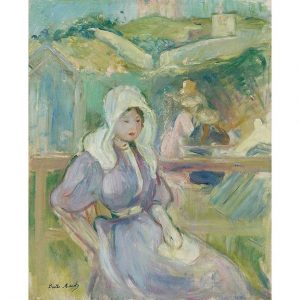

Berthe Morisot, In England (Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight) (1875)

Look at a painting like In England (Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight) (1875). Here, the boundaries are more defined, the frames within frames more obvious. But the ambiguity is there too. Not so much in the brushstrokes, which are more respectful of the lines separating objects and people and areas than they are in Woman Reclining. The ambiguity in this painting, the porousness of boundaries comes from the fact that it is not clear where anyone really is in this painting. Eugene is, of course, very clearly inside a room looking out. But he’s looking out of the window, which is wide open, and which is letting the outside in. And he’s looking at a girl, perhaps his daughter, who is standing at the water’s edge and looking out into a harbor, itself a boundary between sea and land, openness and civilization, water and earth. And we, the viewers of the painting, are looking at Eugene looking at the girl looking at the harbor. Where are we, exactly? Our viewing, our conscious probing of this painting weaves in and out of all these boundaries, boundaries that both hold us, hold our attention, and at the same time, can be skipped over and traversed as if they are nothing. (A more detailed analysis of this painting, making some similar points, was recently published by Jason Farago in The New York Times).

Berthe Morisot, Interior (1872)

Or, in case you still don’t believe me, what about a painting actually called Interior from 1872. Here, a woman sits in a dark gown absorbed by her own thoughts. Behind her, another woman and a young girl stand at the window, itself obscured by the boundary/non-boundary of muslin, a favorite fabric of Morisot and many artists interested in the thin line between that which is concealed and that which is revealed (see any Terrence Malick film). The woman in black is, physically, the person most fully in the room, but the one least there psychologically. She is somewhere else. The woman with the girl in the back is in the room both physically and mentally, but her entire attention is directed at the little girl. The little girl has half-disappeared behind the drapes and is directing all of her attention to the street outside.

Berthe Morisot, Woman at Her Toilette (1875-80)

Or, last example, Woman at Her Toilette from 1875-80. Here, the boundary between foreground, middleground, and background is being collapsed to the point where it takes a minute of looking at the painting just to establish what’s what and where’s where. But it makes perfect sense that the room would be difficult to see clearly when you further explore the situation of the painting. We aren’t seeing this room objectively, but as a result of the experience of the woman at her toilette. And she’s not really in the room, if you know what I mean. Her body is in the room but it’s the mirror version of herself that is holding all of her attention. What we would normally call her ‘real self’ has faded away, as the blurring of her face makes abundantly clear. Her real face, right now, in this moment, her real face is in the mirror. But we don’t get to see that face. We only get a hint that it is there within the boundary of the mirror, a place that has, for the purpose of this painting, sucked most of the reality of the room into itself and left only this blurry indeterminacy as a residue. This painting is the document of what a room looks like to someone whose consciousness is not actually present in that physical space.

The implication of Woman at Her Toilette, as well as the other paintings we’ve just looked at, is that boundaries are real but that they change and shift and overlap according to the situation, and the specific experience of the individuals within those boundaries. You could say that Morisot was trying to paint individual experience into the objectivity of the world. Impressionist painting techniques were a revelation to her because of how well suited they were to capturing the simultaneous existence and non-existence of all kinds of boundaries, especially as those boundaries were experienced by a French woman in the late 19th century.

Berthe Morisot, Sur la plage à Portrieux (1894)

It is intriguing, therefore, that Morisot, in the later 1880s and until her death, started experimenting with a style of painting that re-asserted a strong sense of boundaries, especially the lines that mark out the shape of an individual human being. Take a very late painting like Sur la plage à Portrieux from 1894. There’s just a very different feel to this painting, especially when you contrast it with a painting like Woman in Grey Reclining. There are also strong similarities. We have, in both paintings, a portrait of a woman in the midst of her own subjective experience. But in Woman in Grey Reclining, the nature of that subjectivity, the mood of it, is one in which the strong lines are dissolved. Thus the crucial patch of blurred paint that we discussed above. In Sur la plage à Portrieux, however, Morisot adopted a very different technique. She uses a darker paint that makes the outlines of the woman unmistakable. It’s a technique one sees more often in painters of various traditions we now label Post-Impressionist, painters like Munch or Gauguin or Van Gogh.

Berthe Morisot, Before the Mirror (1890)

Another painting, Before the Mirror from 1890, is particularly striking in this regard because of how directly it contrasts with Woman at Her Toilette. Now it is the person within the boundary of the mirror who has faded into greater indeterminacy. The woman in the room is strongly outlined. The strong outlines make sense because the woman in Before the Mirror has actually looked away from the version of herself within the mirror. Her attention is not directed at the mirror version of herself anymore since she is concentrating on doing something with the back of her hair, which requires her not to look in the mirror, but to feel her own hands and to imagine what is happening at the back of her head, the very view that the mirror cannot capture in this position. This act of feeling and imagining herself has been emphasized, by Morisot, with the strong clarification of the lines that determine her upper body, upon which she happens to be concentrating.

Berthe Morisot, Julie Manet and her Greyhound Laertes (1893)

It’s a startlingly new approach for Morisot. When you look at a painting like Julie Manet and her Greyhound Laertes (1893), with its hard color contrasts and its, let’s say, quasi-expressionistic lines, it is difficult at first to reconcile this painter with the Morisot of the mid 1870s. But I think there is a kind of philosophical continuity here. If Morisot’s constant theme was boundaries, the edges between things, people, objects, landscapes, and the way that human subjective consciousness both establishes and perfuses boundaries, then the later work is but another variation on this theme. Morisot was especially sensitive to those moments in our lives when our experience of self and others melts and drifts, when a reverie or moment of introspection gives us access to the all-pervading unity of life. But the flip side of these moments of unity are the moments when we snap back into self, when we’re called back from the indistinct flow of dreaming to the particularities of a moment. These can be experiences of sudden clarification, the clarification of self and of others.

I find it especially satisfying to know that Morisot was good friends with the Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé in her later years. I can see the two of them sharing an intuitive sense that art must show us something about both unity and difference. The power of Mallarmé’s poetry is in the degree to which he allowed sense and meaning to dissolve almost completely. And yet, not completely. Mallarmé was always aware that individual words carry meaning. He arranged his poetry on the page with a great respect for blank spaces, and for the way that one single word sometimes seems to demand the respect of an entire page. He also understood that individual words get swallowed up by all the words around them, by the syntax and grammar of a sentence. He knew that language was fluid, flowing like a stream or a river in which all combinations of words are possible. But he was also fascinated with the rocks in the stream, the islands and the less movable bits of stuff that resist the flow or, perhaps better said, that give the flow of any body of water its specific shape and contour.

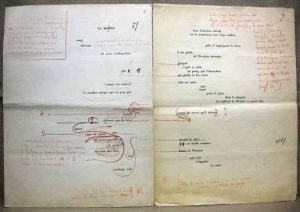

Here, for example, is a page from the first proof of Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés from 1897.

You can look at the page as a drawing, a visual sketch of how language works. And it has a graphic quality not unlike the later paintings of Morisot.

Berthe Morisot, Julie Daydreaming (1894)

It is moving to realise that Morisot’s later style had, as subject matter, a consistent preoccupation with her daughter, Julie. The 1894 painting Julie Daydreaming comes to mind. Here we have a picture of a woman caught in a moment of introspection and reverie, as in so many of Morisot’s pictures. And yet, in this case, the daydreaming of Julie seems not to dissolve her boundaries or to lessen her sense of self. In fact, the opposite has happened. In daydreaming, Julie has become ever more distinctly who she is. There is respect here of mother for daughter, even something I would call awe. It is the awe that one can often witness in parents as they gaze upon their own progeny. Morisot always painted her daughter with reverence for that strange mystery by which someone can be yours, literally created by you, and not yours at all.

In her notebooks at the end of her life, Morisot wrote:

With what resignation we arrive at the end of life, resigned to all its failures on the one hand, all its uncertainties on the other, for so long I have hoped for nothing, and the desire for glorification after death seems to me an overblown ambition; my own ambition has been confined to a desire to fix something of all that passes, oh! Something, the least little thing, well! that ambition, too, is overblown.

Berthe Morisot died in 1895 at the age of fifty-four from pneumonia, which she caught from her own daughter. She died, as she put it, with no regrets. Perhaps it was an overblown ambition, but I would say that she did, indeed, fix a little something of all that passes.