Color is Meaning

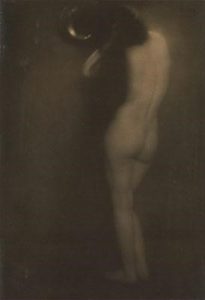

It is said that the great Luxembourgish-American photographer Edward Steichen once took a thousand pictures of the same white teacup. This was in the days before digital photography, mind you, so the commitment of time and expense was considerable. Steichen photographed the teacup against different variations of white and black backgrounds. He was studying his art, trying to get the nuances of light and contrast just right. The result of such studies is a photo like The Little Round Mirror (1901, printed 1905), which is a classic work of early Modernism in photography. The posing is sculptural. The print has so many painterly qualities that it might possibly be taken for one (a painting, that is).

Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art (33.43.32)

Now fast forward seventy years or so. It is 1976 and John Szarkowski (the incredibly influential Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art from 1962 to 1991) exhibits the photographs of a man named William Eggleston. The show includes a shot (titled, simply, ‘Algiers, Louisiana’) of an aging dog lapping up water from a brown puddle in front of a parked car and a suburban home. There is nothing sculptural about the shot, nothing painterly either. It has none of the studied artiness of a Steichen photograph. Given the short length of time dogs generally spend lapping water, Eggleston couldn’t have had more than minute or so to compose and execute the shot, if that.

Image: Eggleston Artist Trust

The exhibition of Eggleston’s photographs at Museum of Modern Art therefore caused something of a stir among people interested in art photography. ‘Serious photography’, from roughly its inception in the mid-nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century, was supposed to be deeply studied in terms of framing and composition. It was supposed to contain ‘important’ subject matter (be that other works of art, social commentary, serious portraiture, etc.). And it was supposed to be in black and white.

“Perfectly bad … perfectly boring”

William Eggleston’s photographs were none of those things. Eggleston even let it be known that he sometimes “composed” shots without even looking through the viewfinder. That’s to say, he was (and remains) deeply uninterested in the traditional painterly or photographic notions of composition. This creates photographs that can look, at first glance, almost indifferent. The fearsome New York Times critic Hilton Kramer, reviewing Eggleston’s show in 1976, wrote that it was, “perfectly bad, perhaps… perfectly boring, certainly.” One can understand Kramer’s exasperation. Who cares about a snapshot an old dog satisfying her thirst in a suburban mud puddle?

There were, however, a few critics who immediately saw that William Eggleston was doing something fresh—and potentially exciting. Janet Malcolm wrote a piece about Eggleston’s photography for The New Yorker in 1977 entitled “Color.” It was later collected in her now canonical book Diana and Nikon: Essays on Photography. Malcolm sensed that Eggleston’s photographs could not be so easily dismissed. She realized that, in Eggleston’s photographs, she was being confronted with genuine art, though art that seemed to come from a photographic sensibility distinctly different from that of Steichen or Stieglitz or any of the other great photographic Modernists. Eggleston was breaking that mold.

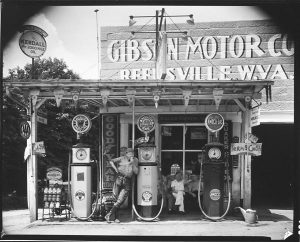

Not that Eggleston’s aesthetic sensibility rose up ex nihilo. Eggleston (Malcolm and others argued) belongs in the ‘vernacular’ tradition of photography, a tradition developed by people like Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. Look, for instance, at Walker Evans’ photo of a gas station:

Or Dorothea Lange’s picture of men sitting on a bench in Depression-era San Francisco:

This American vernacular style continued into the 1960s ‘street photography’ of photographers like Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand.

Janet Malcolm calls this “Photo-Realism.” She writes in her “Color” essay that Eggleston takes us deep into Photo-Realist country and that such country “is defined by the presence of recently made structures, machines, and objects; by people dressed in clothes of the cheap, synthetic, democratic sort; by the signs and the leavings of fast food, fast gas, fast obsolescence; by the inclusion of the very parts of the landscape that photographers used to try to eliminate, edging the bridal couple away from the parked cars, angling the lens to exclude the Laundromat sign encroaching on the quiet tree-lined street.”

Working within this Photo-Realist tradition, Eggleston’s special contribution was his decision to abandon black and white and shoot his photos in color. The decision was bold for one specific reason. If you look at the street shot of a pregnant woman hailing a cab by Garry Winogrand, you’ll notice that there is very little to distinguish the picture from any number of snapshots taken by any number of amateur photographers. You might have a box of such pictures in your own basement somewhere. How, then, is a fine art photographer shooting in the vernacular style to distinguish her work from just another snapshot? Keeping to black and white, especially after the emergence of cheap color photography for the masses, was one approach to this problem. The most serious art photographers always shot their pictures in black and white and generally paid close attention to matters of composition, framing and contrasts between light and dark.

Look – color!

Shooting in color, as an art photographer, was therefore a potentially dangerous muddying of the waters, a blurring of the boundaries between highbrow and lowbrow photography. But William Eggleston seemed not to care about such boundaries and distinctions. He wanted his pictures to be in color, and that was that.

In her “Color” essay, Malcolm brings up a compelling practical reason for Eggleston’s preference. She makes the following observation about a photograph from “William Eggleston’s Guide” (the book published alongside Eggleston’s 1976 show at MoMA) of an aged woman smoking a cigarette while sitting outside on a chaise.

The woman is sitting on and against cushions printed with a riotous pattern of yellow and orange and green flowers; her dress is another bold floral print, in magenta, blue, and red; above her head is a pattern of sun-dappled green leaves seen through the grid of a white lattice; and, finally, at her feet is yet another pattern, of dead leaves on flagstone. In black and white, these patterns—and, so to speak, the woman, the chaise, the leaves, the flagstone—would cease to exist.

Image: Eggleston Artist Trust

My copy of Diana and Nikon proves Malcolm’s point; the book is not in color. So, I’ve seen the shot in black and white and the various colors and patterns do indeed merge into an indecipherable mass. The woman disappears. You wouldn’t look at the picture twice in black and white. But in color, it is something else entirely. In color, “an atmosphere of romantic melancholy wafts out of [the] commonplace subject matter.”

Colors, according to Malcolm, compliment and add “atmosphere” to what she calls the “commonplace subject matter” of Eggleston’s photography. The net result of this combination between a street photographer’s American vernacular style and the use of color created pictures that were once described, rather lyrically, by John Szarkowski, as:

… fascinating partly because they contradict our expectations. We have been told so often of the bland, synthetic smoothness of exemplary American life, of its comfortable, vacant insentience, its extruded, stamped, and molded sameness, in a word its irredeemable dullness, that we have come half to believe it, and thus are startled and perhaps exhilarated to see these pictures of prototypically normal types on their familiar ground, grandchildren of Penrod, who seem to live surrounded by spirits, not all of them benign.

Such is the critical consensus around Eggleston today. Szarkowski and Malcolm created it. Eudora Welty enhanced it with her influential introduction to The Democratic Forest (a book of photographs published by Eggleston in 1989). To date, a version of this argument has been taken up by numberless critics and journalists in articles and essays written all over the world. Two core thoughts predominate about Eggleston, that he shoots mundane subject matter and that he uses color to add fascination to the mundane. These have been repeated, in one variation or another, more times than can be counted.

__

It isn’t wrong, exactly. But perhaps it is time, forty years after Eggleston’s big debut at MoMA in 1976, to question a few of the basic assumptions that, for so long, have been the animating force behind this story.

First, I’m not so sure that the subjects of Eggleston’s photographs are as commonplace as people take them to be. Yes, Eggleston mostly does his work along the byways of the America South. But the streets of Memphis and the back roads of Mississippi and Alabama are not commonplace to most people. It is a world, even for most Americans, as exotic as a foreign land. The great population centers of America are urban areas that bare little resemblance to the southern landscapes Eggleston has consistently sought to portray. This was already true in the 1970s, when Eggleston took up his work in earnest. It has only become truer in subsequent years.

So, Eggleston is not primarily in the business of taking photographs of objects, people, and scenes that anyone and everyone can see. He’s in the business of capturing scenes that only he can see, that he is in a privileged position, as a lifelong southerner, to notice, to view and, therefore, to bring to our attention.

Then, there is the question of color. Repeating, again and again, that Eggleston helped pioneer a move toward color in ‘serious photography’ doesn’t say much – well nothing, really – about what Eggleston actually does with color in his photographs. According to Szarkowski and Malcolm, all we need understand about Eggleston and color is that he faithfully records it. In her essay on Eggleston, for example, Malcolm quotes a line from John Szarkowski. Szarkowski writes that photographers using color (like Eggleston) have, “a more confident, more natural, and yet more ambitious spirit, working not as though color were a separate issue, a problem to be solved in isolation (not thinking of color as photographers seventy years ago thought about composition), but rather as though the world itself existed in color, as though the blue and the sky were one thing.”

This thought could be restated as the following: Eggleston shoots in color because that’s how we see the world—nothing more, nothing less. According to Malcolm and Szarkowski, Eggleston uses photography as a tool of realism. As a photographer, you show the world as it is. Color is one important part of ‘how the world is’. That’s more or less the basis for the argument that Eggleston’s vernacular style and his use of color go hand in hand.

But let’s look at a picture by William Eggleston and try to figure out if his use of color is really so “vernacular.”

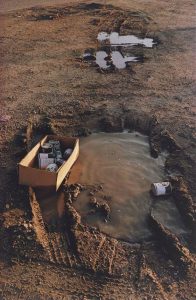

In 1973, Eggleston shot a picture titled Mississippi. He made a print of the picture in 1980, which now belongs to the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum. The picture is a shot of the ground, taken from about ten or fifteen yards away. We see dirt, mud, tire tracks, and a couple of puddles. The largest puddle, in the foreground of the shot, contains, on one side, a box filled with empty cans. One can lies outside the box on the other side of the puddle, lonely and half submerged in the muddy water. Most of the cans are Quaker State oilcans, though if you look closely, you’ll notice that two smaller cans of Schlitz beer nestle amid the larger cans of Quaker State.

Image: Eggleston Artist Trust

Not the Obvious

It’s a bleak scene that Eggleston has captured somewhere, presumably, by the side of the road in rural Mississippi. Yet the photograph is lovely. The photograph would not be quite so lovely in black and white (run it through Photoshop if you don’t believe me). Color is crucial to the shot. The long shadows and the warmth of the light suggest that this shot was taken either in the early morning or in the later evening. I suspect it is an evening shot, mellowed with that specific light that is a favorite of film director Terrence Malick, and that has sometimes been described as light of ‘the magic hour’. This magic light illuminates the dirt and the mud and the cardboard box filled with empty cans.

The light does not suppress or deny the inherent sadness, the disturbing aspects of the scene. The oilcans are a blight on this little patch of pathetic earth. The tracks made from the truck tires in the mud have created the vague sense of a wound. The scene is unpleasant. But the color of the light, the golden tone it brings to the brown of the dirt and the mud—this effect is transformative. It is not entirely unlike what I suspect Bellini was trying to achieve in his painting of Christ’s Transfiguration. This scene of oilcans and dirt has been transfigured; the light and the color are doing that work of transfiguration.

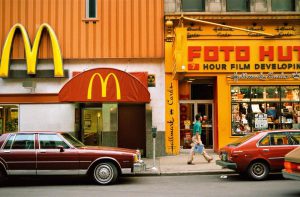

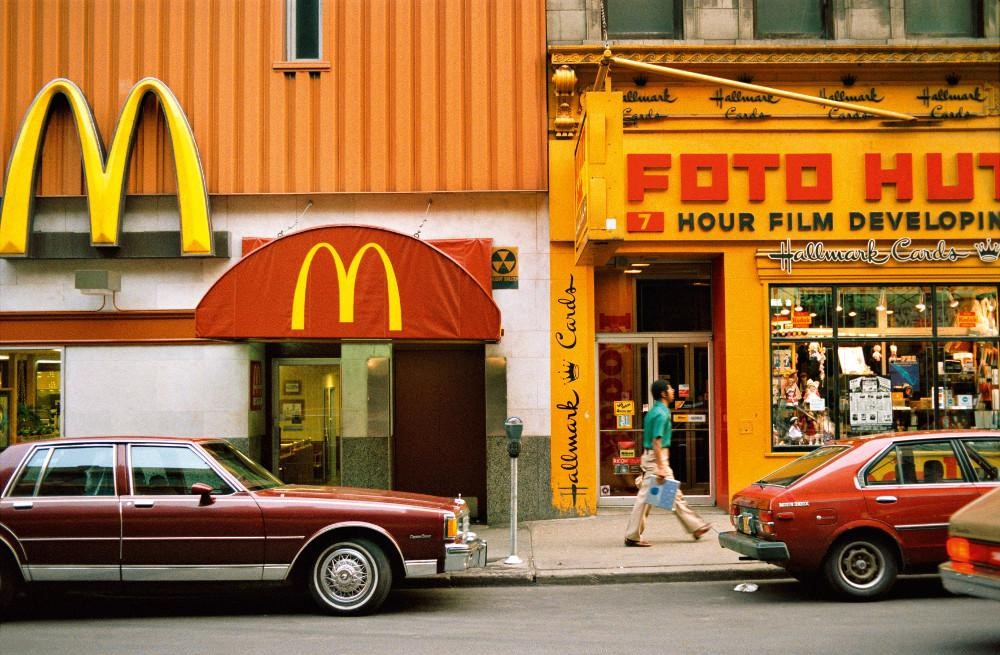

Let’s look at another shot, this one a street scene. The picture features a McDonald’s, a Foto Hut, two cars parked on the street, and a pedestrian walking by in a green shirt. The colors red, orange, and yellow dominate the photograph. Otherwise, the street scene is deeply uninteresting, even squalid. Here’s the trash and the muck of contemporary consumer culture with its fast food and Hallmark Cards and 7-hour film developing. If Malcolm was right that Eggleston is all about Photo-Realism, here it is, wall to wall.

Image: Eggleston Artist Trust

But the real power of the photograph is in the color. There is so much orange. A dark, red-hued, rusty orange, and a lighter, more electric, artificial orange that blends into the dazzling yellow of the Golden Arches. The hint of green, in the shirt of the man walking by and reflected in several of the glass surfaces (the car, the McDonald’s entrance, the Foto Hut windows), heightens the droning hum of the orange. Looking at this photo, it becomes clear that Eggleston has been doing something with color photography not dissimilar to what the important German Expressionist painter Franz Marc was doing in a painting like Yellow Cow (1911).

Marc, like Eggleston, was interested in looking deeply into the vernacular of everyday experience. But Marc was also aware that the world deeply gazed upon transforms from the thing we thought we were seeing into a more intense experience. Color, for Marc, is the key to this transformation. Yellow, red, blue, green; the experiencing of color was not, for Marc, a byproduct of our interactions with our immediate environment. Our experience of color, instead, is what makes the world ‘our own’. It’s what gives a particular place at a particular time it’s special flavor, mood, inflection. Color, in short, is meaning.

Here, Eggleston has always been, if secretly, an artist closer in spirit to someone like Franz Marc than to any street photographer. Eggleston works hard on color. He wants his colors to look a certain way. Commentators often throw out as an aside that Eggleston, throughout his career, has created most of his prints through a “dye transfer” process. This process tends to have a heightening effect when it comes to color. Then, the discussion usually returns to the matter of Eggleston’s ‘mundane’ style and his ‘snapshot’ approach. But wait a second! How can you be both detached, indifferent, committed to the mundane as mundane, and print your work through a laborious, expensive method that enhances, alters, and ultimately transforms and transfigures the image found on the negative?

Eggleston’s dye transfer printing process seems to contradict much of what Szarkowski and Malcolm have tried to tell us about Eggleston. We’re forced to see that Eggleston is actually a wily agent. He is manipulating his pictures in order to create something, via color, that has little to do with the images of the actual world we encounter on a daily basis. This, I think, is what Eggleston was trying to tell us in his oft-repeated, though rarely understood saying, “I’m at war with the obvious.”

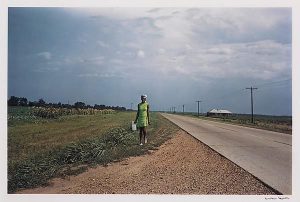

Let’s look at another shot from the Guide. The shot is labeled Near Minter City and Glendora, Mississippi. It shows a country road, a big open sky, a field full of crops off to the left, and a woman walking toward us along the side of the paved road. She is carrying a small bag. The woman is African American. She is wearing a hairnet and a green dress.

Image: Eggleston Artist Trust

If this picture were taken in black and white, it would not be an especially interesting picture. The color does nearly everything to make this picture extraordinary. But why is it extraordinary? It’s just a snapshot of a young black woman walking down the road in rural Mississippi.

It’s the dress. The green dress pulls the picture from the realm of cliché into something much harder to define. The green of the woman’s dress is too spectacular. It is not the dress, nor the green, of a farm worker or a rural black woman of our clichés. A natural green, tattered dress is what we might expect of a ‘documentary style’ photograph that, say, aims to record the conditions of African Americans in the rural Deep South. That would be the ‘obvious’ picture, the expected shot (especially as taken by someone not from the South, but going there to ‘document its ways’).

Instead, Eggelston captured the dress of someone going to a party. It is the green of someone showing off. The dress is not the natural green of the grass and plants off to the left of the photo. It is the green of unnatural dying and textile techniques. That’s to say, this young black woman walking down the road in rural Mississippi is a modern American woman wearing a dress, with its two rows of large buttons, right from the pages of a fashion magazine.

This study in green is therefore a study of a color at war with itself. Green is the color of nature here. But it is also the color of anti-nature. Green is a rural color. But it’s also the color of artifice, a link to the urbanity that hovers, unexpectedly, just outside the frame of this photograph.

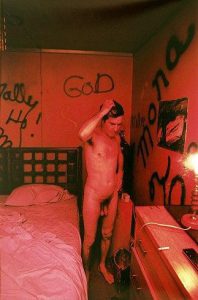

If Eggleston’s bold photographs say anything about color itself, they certainly do not claim that color is simple. Eggleston is constantly aware, for instance, of the fact that we tend to associate the color red with danger. But he is also aware that red works best as a danger color when it is an accent, when it jumps out against other colors. Too much red in one scene creates a sense almost of impotence, of exhaustion. Eggleston’s best ‘red’ photographs capture both of these qualities at once.

Image: Eggleston Artist Trust

The poet Christian Wiman once wrote of, “color slowly aching into things, the world becoming brilliantly, abradingly alive.” It is a sentence one ought to keep in mind when looking at the pictures of William Eggleston. In the year 2017, as mobile devices have made ‘street photography’ ubiquitous, as we’re flooded with images of daily life on a daily basis, it is more important than ever, I think, to reflect upon what has made the photography of William Eggleston different. The mundane, as such, was never the key. It is his transfiguration of the mundane that makes Eggleston’s pictures truly works of art.

Color is the key to that transfiguration. It is the green of the young woman’s dress that tells us a story about aspiration, about the expression of personal ambition. It is the orange of the Foto-Mat store that reminds us about the visual decibels of street life. And it is Eggleston’s red that communicates the feeling of “I am here now but I am not sure it’s where I want to be”.

Eggleston’s sensitivity to color, his laborious printing process, his desire to create prints that heighten and augment the colors in his photographs, all of this brings his artwork into a tradition that goes back to Venice in the days of Titian. This is a tradition that unites Turner and Van Gogh, Delacroix and Matisse, everyone for whom color is the central mystery of visual art, the centripetal force of power and meaning in a picture. To look at Eggleston’s pictures as one would look at a snapshot or as an example of the “vernacular” style of Photo-Realism would be to miss the importance of his singular achievement in the history of photography. Eggleston brought color to life.