Armor for contemporary living

There’s a woman standing against a white background. Doll make-up has been applied to her face, big round areas of red rouge on her cheeks, exaggerated mascara, the works. She’s bent over to her right but looking forward with a bemused expression. Perhaps this is because she is struggling under the weight of what I can only describe as a shag rug with polka dots. Also, she’s topped off with, I don’t know, a tuft of round bark serving as a hat and covered in dried flowers and lichen.

Another person, gender unknown. They are wearing an oversized pair of white button-down long underwear. Really oversized. The person is pulling the material out from the hips with both hands and the result is a giant trapezoid. The long underwear trapezoid, or maybe we should call it a onesie, is tucked into baggy leg warmers. Also, they’ve donned a dirty beat-up prospector hat possibly stolen from the costume closet of the 1974 feature film, The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams.

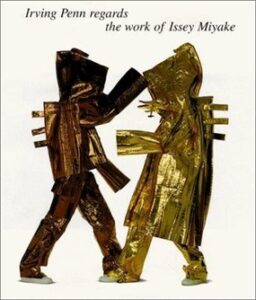

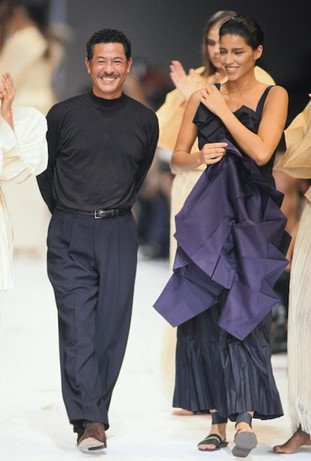

These are but two examples of what can be discovered flipping through the pages of a book titled Irving Penn regards the work of Issey Miyake (1988). Irving Penn was one of the great fashion photographers of the 20th century. He worked at Vogue for many years and also did his share of portraits and still lifes. Issey Miyake, who died in August, was one of the great fashion designers of the 20th century. So, the book is a rather extraordinary collaboration.

It is said that Miyake gave Penn full license to make his clothes look however Penn wanted the clothes to look. Penn would sometimes do odd things, like having the models wear the clothes backwards. Though, to be fair, it is not often clear which way is which with much of this clothing. Miyake didn’t care. He found the pictures inspiring and always loved Penn’s fresh take on his designs.

I don’t remember exactly where or when I came across the book. I know it was in New York City sometime in the 1990s. I know that the book made a visual impact because I’ve remembered it ever since. When I heard that Miyake died, it was the first thing that came to my mind.

But I bring up the crazy and sometimes hilarious shapes and designs in the book for a more specific reason, and it is not to poke fun at haute couture, a tired exercise that was already boring more than a century ago. I bring up the book because Miyake was a fashion designer whose work demanded to be taken seriously as both fine art and popular culture. His ready to wear designs were, and remain, hugely successful. He was also the sort of fashion designer whose designs the editors of Artforum had no qualms about featuring on the cover of the magazine. Given his recent death, it seems a worthy endeavor to say a few loosely related things about what made Miyake so special.

Miyake’s unique fashion sensibility is undoubtedly related to Issey Miyake the person. He was, by all accounts, an exceptional individual. His biography begins in the Second World War. Miyake was seven years old and living in Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped. His mother died of radiation poisoning weeks later. In a remembrance of Miyake published recently at n+1, Miyake is quoted as saying, “I seem to be present at occasions of great social change, Paris in May ’68, Beijing at Tiananmen, New York on 9/11. Like a witness to history.”

What’s remarkable, though, is that for a person who witnessed and reflected upon so much historical trauma and upheaval, Miyake managed to make clothing that was always generous and kind. These are words that one doesn’t often associate with high fashion. Karl Lagerfeld, for instance, once said, famously, “Sweatpants are a sign of defeat. You lost control of your life, so you bought some sweatpants.” True perhaps but mean. Vivienne Westwood has also been known to spend the greater part of a day insulting people. “Everybody looks like clones,” she said recently, “and the only people you notice are my age. I don’t notice anybody unless they look great, and every now and again they do, and they are usually 70.”

Contrast this with Issey Miyake, who once said of his fashions, “the clothes are for people to dance and laugh.”

Miyake’s death inspired an outpouring of gratitude and verging-on-sentimental memorializing even from outlets (like the just-mentioned n+1) that don’t normally go for such soft-hearted stuff. A consistent theme in all these tributes is summed up by Jane Hu, who wrote in her n+1 piece that, “His were designs of and for the living.”

I suppose it would have been odd for a fashion designer to make designs of and for the dying (though Alexander McQueen sometimes came close). But the comment is not to be taken literally. By “living,” Hu means something more than the physical fact of being alive. She means that Miyake’s designs could be worn by actual people in the real world. Wearable. Normally in the fashion world, wearable is a fighting word, an insult. Think, again, of Lagerfeld’s comment about sweatpants. Sweatpants are wearable. High fashion, by contrast, is generally aiming for something loftier, more profound. High fashion, in short, is a form of high art.

But Issey Miyake managed to be interested in real life, real bodies, wearable clothes, and still maintain his high-fashion credibility. Maybe his greatest accomplishment was, therefore, to have tackled polyester. Polyester is not high fashion. Polyester is embarrassing. The people pitied by Karl Lagerfeld, the ones who’ve given up, are the sorts of people who wear polyester clothing.

When Issey Miyake launched a diffusion line (a secondary and lower-cost line) in 1993 he called it Pleats Please. I’m certain I do not understand all the science and engineering behind the garments. Suffice it to say that Miyake and his team somehow managed to mess around with polyester enough (cut it, bunch it, steam it, run other fibers through it) to create items of clothing that have permanent pleats. The pleats create a sense of elegance and structure to the garments. But because it is polyester, it doesn’t wrinkle and is easy to clean. It is durable and long lasting. You can put Pleats Please garments in your luggage and they come out again looking great. You have to take care of Pleats Please garments, don’t get me wrong. But for designer fashion, even of a diffusion line, the stuff is remarkably unfussy. Perhaps most astoundingly, the official instructions for Pleats Please recommend that you place the garment “in a washing net bag and machine-wash on short cycle or hand wash at a maximum temperature of 30 degrees Celsius.” Putting it in a washing machine? That is downright sacrilegious for a fashion line.

The effect of these garments—Pleats Please, but also many of the other clothes Miyake made in the last forty or so years of his life—is to make the people who wear them, particularly women, feel like they’ve been cared for. Witness the writer Haley Mlotek on Miyake: “His clothes exist almost out of hierarchy, unmistakable to see and yet blending entirely into the wearer’s personality—when the owner of the gallery wears them on the same day as the curatorial assistant, and even though there is certainly a formula to these fits, they both look like they’re dressed like themselves.” It is notable that in comments like these, again, especially from women, there is little talk of looking sexy or attractive or alluring. Not that such things cannot happen in Miyake clothing. But that’s not their primary purpose.

What the clothes do instead is convey a feeling of freedom. Or that, at least, is what so many people who love them constantly say. Here is how Elaine Louie and Elizabeth Paton describe this feeling of freedom in their New York Times obit for Miyake:

To wear a Pleats Please piece was to discover a lack of bodily constraint and, with that, Mr. Miyake hoped, a lack of emotional and creative inhibition.

Most Pleats Please clothes had no buttons, zippers or snaps. There were no tight armholes, or delineated waistlines. They slipped onto the body and were opaque enough to require only minimal underpinnings — say, a bra and panties. Necklines weren’t so deep as to be revealing. Often Mr. Miyake used solid colors — blues, greens, crimson — or fabrics printed with flowers or tattoos.

Reading commentary like this, one could be forgiven for thinking that Miyake made something more like costumes, or even armor for contemporary living. Mark Holborn, in his somewhat rambling introduction to Irving Penn regards the work of Issey Miyake, writes, “As a scream becomes the dominant expression, one longs for a place where the shouting ceases. Now everything is shouting–not least the world of fashion. One could turn away to, say, the language of the Heian court or the nuance of the Noh stage in a fantastic Japan of one’s imagination. However, on the cusp of an exceptional moment in the calendar, one has to look to the future and draw from the diversity of a truly global culture which the future promises.”

I don’t think this is too far from the truth. And I would say that this comes directly from Miyake’s 20th century biography. That’s to say, the traumas and dislocations of recent history have made even seemingly simple choices, like what kind of clothes to wear, ever more complicated. Miyake understood this quite well. He came from a city, Hiroshima, that had been essentially vaporized by the most terrifying weapon of the modern age. The rest of his life was peripatetic. He was Japanese, but also to some degree French, having apprenticed with Guy Laroche and worked with Hubert de Givenchy in the 1960s. And then he was off to New York, working for Geoffrey Beene, but also hanging out in the downtown art scene and palling around with people like Robert Rauschenberg. He continued to bounce around the planet for the rest of his life.

The bewildering possibilities, the fragmentation of history, the patchwork of different identities that constituted Miyake’s life are tacitly acknowledged in the clothes photographed in the Irving Penn book. Some of the clothes look super-futuristic, with lots of silver and metallic-looking surfaces. A few could be described as outfits for robots. Other pieces have a folksy vibe and seem to be made with lots of twine and burlap. One outfit seems to reference Japanese traditional wear: kimonos and Noh theater. Another looks like it’s meant to be worn by clowns on a mission to outer space.

Issey Miyake managed, in short, to take the jumbled up and fragmented sartorial history of the recent past, mix it up with wild fantasies and dark forebodings of the future, smash new synthetics together with organic fibers, invent completely new processes for making clothing, face, head on, the inherent absurdity of wearing clothes at all, and then make all of this somehow feel cozy and comforting.

The secret behind all this madness was that Miyake didn’t really care how you looked, he cared how you felt. Obviously, the two things are related. It is hard to feel good if you look like crap, or more importantly, think that you look like crap. But Miyake was able to make clothing that made the people inside the clothing feel so confident they almost always looked good. He managed to create a kind of soft and gentle armature against the uncertainties of contemporary life and, especially for women, against the constant pressure of bodily perfection.

Accomplishing this was trickier than it might seem. To me, some of Miyake’s less successful designs fail precisely because they look and feel too much like armor. Take, for instance, some of the dresses that resemble lampshades or paper lanterns. The clothes have lost any meaningful contact with the bodies inside.

But most of the time, Miyake got it right. And in getting it right, he probed the inner contradiction that exists at the very essence of wearing clothes. Because to wear clothing at all is to become both more yourself and less yourself at the same time. What’s more intimately our own than clothing, after all? We wear clothes every day. It is the most immediate and direct expression of who we are. I would wager that most human beings, if asked to picture themselves, do so wearing some particular outfit. Many of us feel more awkward naked than we do clothed.

Covering ourselves, dealing with the essential fact of our nakedness, is at the very heart of self-consciousness in many folk and religious traditions. The first event to transpire after Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit is that they no longer tolerate their own nakedness. They become, in those moments, the first fashion designers. From that moment on, metaphorically speaking, a central human question becomes, “What to put on?” How should one appear? And what is the relationship between this appearance and the person who appears?”

Miyake has no final answer to these philosophical questions. There are no final answers. But perhaps Su Wu best sums up Miyake’s respect for the dilemmas inherent in the pressures of being clothed in her tribute to Miyake in the aforementioned n+1 piece.

“Style—no matter how subjective the vagaries of taste—is almost always an act of communication, a bid for approval…. I want you to think I am beautiful, or failing that, I want you to think I am rich, or even worse, I don’t care what I look like, which no one believes anyway.

Issey Miyake helped me try to reconcile the hypocrisy and compromise that forms around caring how you look. His designs allowed me to love clothes, and love them to a fault, but to keep from them what I wanted and not have to give them up completely, for having nothing really to say. Miyake’s clothes, in other words, do not make your butt look good.”

Maybe the popular art of Issey Miyake is best described as the art of not making your butt look good. But in saying that, we are also saying that it is the art of accepting the madness and pressure of contemporary life with a comfort and ease that moves and flows with the suppleness of a Pleats Please blouse. Miyake, let us never forget, is the fashion designer who made it possible to love and to cherish polyester. Actually, he always balked at being called a fashion designer. Fashion is something fleeting and exclusive. For all his refinement, Miyake was a Romantic and a populist at heart. He wanted to make art that could be worn by everyone and anyone, and that therefore contained an element of timelessness. “I don’t make fashion,” he’d always say, “I make clothes.”