Ancient or modern? The perplexing case of indigenous art

There’s an unexpectedly amusing passage in the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment. Kant is deliberating upon lofty issues like how and why we consider something beautiful. In the course of his complicated philosophical maneuverings he pauses to mention, by way of example, a number of pleasing designs to be found in nature. And then, in a twist, he muses briefly on how the eye and mind delight in the incredible shapes and forms of… wallpaper. Yes, wallpaper.

Kant likes wallpaper, and thinks the rest of us like it too, because the shapes to be found on a well-designed piece “mean nothing on their own, they represent nothing … and are free beauties.” That’s to say, we delight in the beautiful forms and shapes of wallpaper precisely because we don’t relate them to anything else. The very fact that the mind doesn’t really know what to do with the shapes or how to categorize them means that we can appreciate them on their own terms.

To me, this is one of the crucial moments in the history of modern art. This essay is not the right place to get into all the twists and turns that take us from Kant’s aside about the wonders of wallpaper to, I don’t know, Morris Louis pouring paint down a tilted canvas in the late 1950s. There is a connection so deep that I sometimes (usually be late at night) convince myself that the entire history of Modernism in art is nothing but an elaboration of a bunch of things Kant wrote about the faculty of judgement, which were later plucked out of context in the early 20th century and which Kant himself was never too clear on in the first place. That is a story for another day.

The pleasure of looking

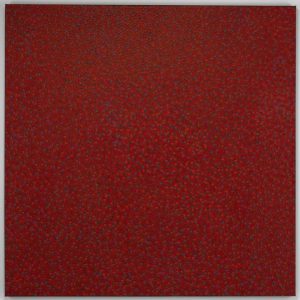

I bring up the history of Kantian aesthetic reflection for a more specific reason. Aboriginal Australians have, for a long time – thousands of years we think, though no one knows exactly how long – been making art that would surely have been pleasing to the eye of Immanuel Kant. This is not to make the potentially insulting claim that Aboriginal art is like wallpaper, though, in a sense that is exactly what I am saying. A person can appreciate many works of Aboriginal art for the very same reason that Kant appreciated wallpaper, which is to say, one can be delighted by the more or less abstract play of shapes and line and color. Personally, I have never seen wallpaper as fundamentally pleasing to look at as, say, Bush Hen Dreaming — Bush Leaves (2003) by Abie Loy Kemarre, a work that presents the viewer with a wonderful display of forms undulating across the canvas in a myriad of tiny strokes of paint.

Abie Loy Kemarre Bush Hen Dreaming – Bush Leaves, 2003. Acrylic on canvas, 71 5/8 x 71 5/8 in. (182 x 182 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Robert Kaplan and Margaret Levi, 2017 (2017.251.1). © Abie Loy Kemarre. Photo by Spike Mafford © 2014

There is beauty here in exactly the way that Kant meant the word, a beauty that comes from the pleasure of looking at designs that “mean nothing on their own.” The mind labors to decide whether the shapes and forms coalesce into a specific and identifiable object or not. The fact that they do not, but instead hover just at the cusp of categorization, results in what Kant called the “play of the imagination.” The longer you stare at Bush Hen Dreaming — Bush Leaves, the more this joyful cognitive-perceptual play emerges as daubs of darker color seem to shift from the foreground to the background of the painting.

Aboriginals first painted this way on their bodies and by making designs in the sand and sometimes on strips of bark. More recently, they’ve been transferring those patterns and designs onto canvases in a nod to the international art market (some works of Aboriginal art are now selling for big money). The works are sought after and collected because they are beautiful in the way that Abstract Expressionist works are beautiful: the play of light and color and shape and form delights us visually. We could easily conclude from this that Aboriginal Australians “discovered” abstract art long before any European or American artist ever hit upon the idea.

The problem is that Aboriginal Australians do not, as a rule, look at their own art in the way I have described above. Aboriginal artists aren’t working with anything like a Kantian conception of a free play of the faculties and they have, in the vast majority of cases, no interest in the idea of abstraction as that idea emerged in European and then American painting in the 20th century. Aboriginal artists have (up until very recently) no conception of art as something to hang on a wall, to enjoy visually and with non-specific cognitive delight. Indeed, many if not most Aboriginal artists are bemused by the idea of “keeping” works of art at all, since their practice is to wash off the body paint or muss-up the designs in the sand after the ceremony is over. Art, for the Aboriginal artist, is less about having and keeping, and more about using and doing. Aboriginal artists make their designs in order to map out sacred sites in the landscape, or to tell important stories, or as an aid to various specific forms of ritual and worship. The idea of putting the work on canvas and selling it to outsiders only came about as recently as the 1970s, and as a way for Aboriginal communities to make some extra money.

Abie Loy Kemarre, for instance, was thinking not about Kandinsky, but about hens and seeds when she made Bush Hen Dreaming — Bush Leaves. The work, for all its abstract beauty, is a map of sorts, a map of sacred sites around Artenya, Kemarre’s ancestral homeland. It also tracks the movements of the bush hen in its search for bush tomatoes, a quest that is mythologized in the ritual tales that Aboriginals call “The Dreaming,” the central narratives that frame Aboriginal life. In short, there is quite a lot going on in Bush Hen Dreaming that someone who purchased the painting and hung it over their couch in the living room might know nothing about. The question, I suppose, is whether this matters. Can we like her painting simply for the ways it pleases the eye? Are we required to understand the painting in the way that Abie Loy Kemarre does?

Bush Hen Dreaming was recently in a small show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The curator of the show, Maia Nuku, chose to exhibit the works not on the first floor, in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas department, but on the second floor, in a “quiet area,” as Nuku put it, of the Modern and Contemporary Galleries. That’s to say, Nuku felt that Bush Hen Dreaming makes more sense, to us, as a work of contemporary abstraction than as something to look at in the collections of cultural artifacts on the first floor.

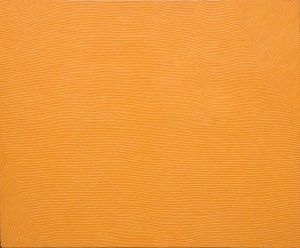

Nuku’s reasoning behind exhibiting the paintings in the Modern and Contemporary art section makes perfect sense. Just look at Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming — Sand-Hill Country (after Hailstorm) by Kathleen Petyarre, which was painted in 2000. The painting is large, more than five feet by five feet. It was made with the careful application of gold and blue dots of acrylic paint on a white canvas. Some of the gold dots coalesce into lines that make their way from one side of the painting to the other. The overall composition is minimalistic. The painting evokes a sense of slow and deliberate time, of something unfolding in an act of meditation or deep reflection.

Mountain Devil Lizard Dreaming – Sandhill Country (after Hailstorm), 2000, Kathleen Petyarre, Gift of Robert Kaplan and Margaret Levi, Spike Mafford Photography © 2014, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS)

I could easily be describing a painting by Agnes Martin. But that’s the point, I’m not. I’m describing a painting by an Aboriginal artist who did not come to abstraction by way of 20th century Western painting. Petyarre came to this kind of (post) Abstract Expressionist painting by way of her own culture, her own practices, her own historical references, which have nothing to do with Jackson Pollock or Franz Kline or Helen Frankenthaler or Agnes Martin. And yet, the paintings in “On Country: Australian Aboriginal Art from the Kaplan-Levi Gift” do seem to be in direct dialogue with all the American and European works of abstraction that can be found in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection.

In an interesting discussion between Michael Cirigliano and Maia Nuku published on the Metropolitan Museum’s website, Nuku tries valiantly to square the circle between the Aboriginal way of making art and the reception of that art in a place like New York City. Cirigliano asks Nuku what the mechanisms are by which a (non-Aboriginal) viewer can understand the storylines of the paintings. Nuku responds:

Well, it’s tricky! These paintings are really accessible on one level because of their formal qualities, and people talk a lot about abstraction, expressionism, the gestural quality of the work, and obviously these interpretations do allow for one vein of understanding the work. What we’ve tried to do in the exhibition is to acknowledge the formal aesthetics of the paintings but at the same time contextualize them in terms of story, and how—and even why—they are made.

There are different ambitions embedded within the art I look after from Oceania. On one level the art is about what things look like, but with indigenous art we want to help people also understand the agency of these things. What is it that the art is doing? What kinds of effects do the works generate? They’re optically fertile and dynamic, so I think people are drawn to them. But then I think we have to help the visitor a bit further into a fuller understanding of the artwork itself.

Modernity and loss

In trying to understand better how to look at Australian Aboriginal art, I spent a few days in Seattle with Robert Kaplan. Kaplan and his wife Margaret Levi (who was out of town) donated the paintings to the Met that were in the Nuku exhibition. Bob and I looked at dozens of Aboriginal paintings hanging all over the walls of their loft in central Seattle. Then we went downstairs, where many more paintings (along with other art objects like carved sculptures) sit in a storage space on the ground floor. We climbed over wooden racks and metal carts and pulled out painting after painting, works that he and Margaret have collected over the last thirty years. One thing became clear as we looked at the work: It is visually stunning. I never got tired of looking at the paintings as we moved around the space, and I had the feeling that Bob felt the same way. He loves any chance to root around in that storage space, just looking for the sake of looking.

But along with the pure visual joy came a sense of sadness. The thought kept returning to my mind that Bob and I were not participating in these works of art in the way that an Aboriginal artist would participate in them. The stories of The Dreaming don’t have any personal resonance for me, or for Bob, even though we are interested and intrigued by them. I should say that Bob knows a great deal about Aboriginal creation stories, and about the specific history of the paintings he’s acquired. But there is a difference between knowing and “knowing” and the time spent exploring that storage space made this abundantly clear. Bob Kaplan is realistic about this fact. He has great sympathy for the lives and stories of Aboriginal Australians, but he likes the paintings because he likes the way they look. In the end, contrary to what Nuku proposes, there is no easy way to get from a pure aesthetic appreciation to any real understanding of what the paintings mean in their traditional context. Being told that a painting of lines and dots is actually a map of sacred sites and a set of secret codes for rituals in which you will never participate is,for me, background information and nothing more.

To be fair, Nuku is well aware of this too. That’s why she begins the quote above with the phrase, “Well, it’s tricky!” It is tricky. Possibly worse than tricky. It may in fact be the case that looking at Aboriginal art is an act of gazing across a cultural-civilization divide that simply cannot be bridged.

This evokes the thought that Modernity is, in some sense, a loss, a loss of a way of being in the world. This loss cannot be reversed. Once you are in the Modern world, you are in the Modern world. There is no going back. A Modern person can travel to the lands of Aboriginal Australia and be told that various sites are sacred and that the sacredness comes from centuries, even millennia, of living on that land. But is a Modern person going to be able actually to experience that sense of the sacred? Not just to hear about it, but actually to experience it?

The obvious response is to point out that Modernity is more gain than loss, so dwelling on the loss is counterproductive. Perhaps this is true. Robert Kaplan mentioned to me, for instance, his admiration for modern plumbing, something not to be encountered in the traditional Aboriginal lifestyle. But to compare pre-Modern life (in whatever variant) with Modern life along the lines of technology and convenience is already to have stacked the deck. The effect of looking at Aboriginal art is to get a glimpse, if only a glimpse, of the fact that we have also genuinely lost something by becoming Modern. Here, for instance, is how the celebrated Australian anthropologist and writer W. E. H. Stanner once tried to explain aspects of traditional Aboriginal life in an essay called “The Dreaming.”

The true leisure-time activities – social entertaining, great ceremonial gatherings, even much of the ritual and artistic life – impressed observers even from the beginning. The notion of aboriginal life as always preoccupied with the risk of starvation, as always a hair’s breadth from disaster, is as great a caricature as Hobbes’ notion of savage life as ‘poor, nasty, brutish, and short’. The best corrective of any such notion is to spend a few nights in an aboriginal camp, and experience directly the unique joy in life which can be attained by a people of few wants, an other-worldly cast of mind and a simple scheme of life which so shapes a day that it ends with communal singing and dancing in the firelight.

I do not think it is possible to read those words without experiencing some pang in the heart, however small that pang may be. Stanner was not unduly romantic about Aboriginal life. He did not cast off the trappings of Modernity and disappear into the bush. But he understood the painful sense of distance and loss by which we Moderns can contemplate a scheme of life in which a day ends in communal singing and dancing in the firelight.

This sense of longing for a form of life that is distinctly un-modern brings us to a second route (the first being formal, purely visual appreciation) by which the overlap between Western abstract art and Aboriginal abstract art can be explored. Contemporary critics, curators, and theorists talk a lot about the formal properties of art, about brushstrokes and mark-making, about the deep interrogation of medium and the self-reflection necessary for making art in the Modern and then Post-Modern era. Much less discussed in serious criticism are the spiritual yearnings, the reflections on Modernity and loss that obsessed many practitioners of Western abstraction from the beginning. Take a look at the written musings of Malevich, Kandinsky, or Mondrian (just to name a few) if you do not believe me. These and many other artists of early abstraction were overwhelmingly occupied with “embarrassing” issues like Spirit, God, the Absolute, the Transcendent, the Soul, the Beyond. Many, if not most, of the “heroes” of Modernism in art, from Picasso to Barnett Newman to Joseph Beuys, were shamelessly at war with Modernity, to greater and lesser degrees. Here, for instance, is Picasso thinking about the importance of what he called “Negro” art.

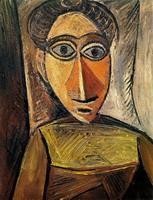

When I became interested, forty years ago, in Negro art and I made what they refer to as the Negro Period in my painting, it was because at that time, I was against what was called beauty in the museums. At that time, for most people a Negro mask was an ethnographic object. When I went for the first time, at Derain’s urging, to the Trocadéro museum, the smell of dampness and rot there stuck in my throat. It depressed me so much I wanted to get out fast, but I stayed and studied. Men had made those masks and other objects for a sacred purpose, a magic purpose, as a kind of mediation between themselves and the unknown hostile forces that surrounded them, in order to overcome their fear and horror by giving it a form and an image. At that moment I realized that this was what painting was all about. Painting isn’t an aesthetic operation; it’s a form of magic designed to be a mediator between this strange, hostile world and us, a way of seizing the power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires. When I came to that realization, I knew I had found my way.

Picasso Pablo, Female Bust (1907)

Now, if you ask your everyday person on the streets of Los Angeles or Chicago or London or Berlin what their definition of art is, “magic” will probably not figure in the answer. This goes doubly for any contemporary critic or curator. We are concerned, popularly and critically, with a rather different question, which is whether we like a work of art or not. There will be different answers to this question. A serious critic will like a work mostly on the basis of how much they think the work is itself asking deep questions about the nature and purpose of art. A normal museum-goer will register “like” in different levels of sensual delight, or “dislike” as annoyance. A politically-minded art enthusiast will like a work dependent on how much it expresses the desired political standpoint or raises the important issues of the day. But the idea that a work of art is not inert, not there to be liked or disliked, not made to be judged or observed, but to be used in a way that can only be described as “magical” -this is an entirely disconcerting and, for most of us, counter-intuitive way to approach art. It amounts, to most people who look at art, I would think, to an affront against our sense of our own modernness. Nevertheless, the fact remains – a great many of the artists who are celebrated in the galleries and museums of Modern art were utterly discontented with the boundaries of “the Modern,” of which they are often considered the exemplars. Along with Picasso, they rejected the Modern idea of aesthetics. Fascinatingly, for our purposes, they would replace the Modern idea of art with something more akin to what the Aboriginal artist has been doing all along: making sacred and ritual objects that mediate between human being and cosmos.

But part of being Modern is, supposedly, to have closed the door on magic altogether. We do not exist within a world in which special objects have special sorts of powers. Thus the general befuddlement experienced by many, if not most people in the presence of works of art. The usual response is to snap pictures of that which is supposed to be important (art) with the help of that which we know is important (our phones). The vague and, I would even go so far as to say, poignantly desperate hope in this act verges itself upon the magical.

Getting an image of the “important art” onto your phone is a way of capturing and thereby taking some share in the impossible-to-define significance of this object, which both does and doesn’t have special status. Our confusion is understandable since works of Modern and contemporary art are, in a sense, documents of the historical process by which art has been divested, though not completely, of all previous purposes and powers. What, really, is one supposed to do in the presence of, say, Barnett Newman’s ocean of transcendent and vibrating blue known as Cathedra?

Cathedra Barnett Newman 1951, oil on canvas, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

The phone might be one’s only defense against a rising tide of deep disquiet. An exactly similar mix of desire and distress is created by senior Aboriginal artist George Tjungurrayi’s untitled (2007) with its pulsating lines that Tjungurrayi once described as capturing the essence of a wooden spear as it vibrates and quivers in flight.

George Tjungurrayi, untitled, 153 x 122 cm, acrylic on linen; image courtesy Utopia Art Sydney

Exultation

A potentially exciting, though also deeply unsettling thought begins to emerge as one reflects upon Australian Aboriginal art and its relationship to Western abstraction. The question becomes less “How can we relate to Aboriginal art?” and more “How can we relate to any art?” Because in many ways, Barnett Newman was trying to make art that functions more like the art of George Tjungurrayi and not the other way around. Newman, for instance, was famous for saying and writing things like, “We have lost contact with man’s natural desire for the exalted, for a concern with our relation to absolute emotions.” Whatever Newman meant, exactly, by “absolute emotions” (and he was the first to admit that too much talk about works of art often leads to incoherence), he nevertheless tapped into something we can all more or less understand, if not fully define. That lost sense of exaltation seems to be precisely the sort of thing expressed by the art of George Tjungurrayi and Abie Loy Kemarre and plenty of other Aboriginal artists.

What is interesting is that those of us who are not Aboriginal Australians still seem to receive something meaningful in our confrontation with the paintings of Aboriginal artists, something close to Newman’s lost exaltation. This comes first from the undeniably stunning visual presence of so many of these works. Christopher Hodges, an artist and art dealer in Sydney who has done much to promote Aboriginal art over the last few decades, described to me his first experience seeing a painting by then unknown artist Emily Kngwarreye (who later became one of the most highly celebrated and collected Aboriginal artists). Hodges said he just knew he was standing in front of a great painting, by a great artist.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, untitled (Alhalkere), 1993, 173 x 200 cm, acrylic on polyester, image courtesy Utopia Art Sydney

But what do we make of this greatness? Kngwarreye (1910 – 1996) only started painting when she was close to eighty years old. She did not go to art school. Her only connection to visual culture was to the ancient traditions of Aboriginal art. But according to Hodges, she immediately began playing with those traditions on her canvases, innovating new styles with just as much boldness as a Kandinsky or Picasso. At the same time, her work never lost its sense of connection to the particularities of her land and her stories. The balance between particularity and universality somehow carries through to the rest of us. Christopher Hodges often downplays the background stories of the Aboriginal art he sells precisely to highlight the fact that the work is valid on its own terms, great simply by virtue of what the eye is confronted with on the canvas. But he is also the first to acknowledge that the works are the carriers of an embedded depth of meaning that transcends their purely formal qualities. The paintings wouldn’t be so visually stunning if this greater meaning were not present.

Kngwarreye was a woman of few words. Like so many other artists, she preferred making the art to talking about it. When Christopher Hodges asked her about the meaning in her paintings, she simply patted one of the canvases gently and said, “You know.”

One of the last paintings Kngwarreye painted just before she died in 1996 would be hard to identify as an Aboriginal work at first glance. It looks, actually, a lot like a Lee Krasner (Jackson Pollock’s wife). It’s a canvas covered in red and orange and brown and a pink that has settled somewhere in the middle. But then you notice a few of those characteristic dots. Maybe the dots are the tracks of the bush hen or the devil lizard, the marks made by the haunches of a woman squatting in the desert sand, the precise location of a waterhole in the desert landscape. No matter. Kngwarreye knew the importance of those dots across her abstract landscape.

Do we, somehow, know too?