“How to See the World Properly”: An Interview About Jasper Johns

Roberta Bernstein is professor emeritus of art history at the University of Albany, State University of New York. She is also the author and director of the catalogue raisonné for Jasper Johns. Most recently, she co-curated (with Edith Devaney) a retrospective of Johns’s work at the Royal Art Museum in London entitled “Something Resembling Truth” (for which I contributed a catalogue essay). The show runs through to December 10 and then travels to The Broad in Los Angeles from February to March, 2018.

Morgan Meis: Let me start out by asking how you first got interested in the work of Johns…. what drew you in?”

Roberta Bernstein: When I was a college student at the University of Massachusetts, I attended a John Cage concert. When afterwards I asked him where I could hear another concert of his work, he told me he was next at a college in Connecticut performing with Merce Cunningham. He also mentioned that I should see Jasper Johns’s art–there was a show in New York. I attended both the Cunningham performance and went to NYC to see the Johns retrospective at the Jewish Museum (this was spring of 1964). I was deeply affected by Jasper Johns’s art–it confronted me with a new way of seeing and thinking and it challenged my eye and mind to perceive art and the world in a new way. When I moved to New York to attend graduate school in art history at Columbia I met Jasper Johns (at the Leo Castelli Gallery). He invited me to visit him at his Riverside Drive apartment near Columbia and then worked for him part-time during my graduate studies. I was determined to do a PhD thesis on a contemporary artist (which had never been done at Columbia) and ended up doing it on Johns who, for me, has remained the most compelling of current artists.

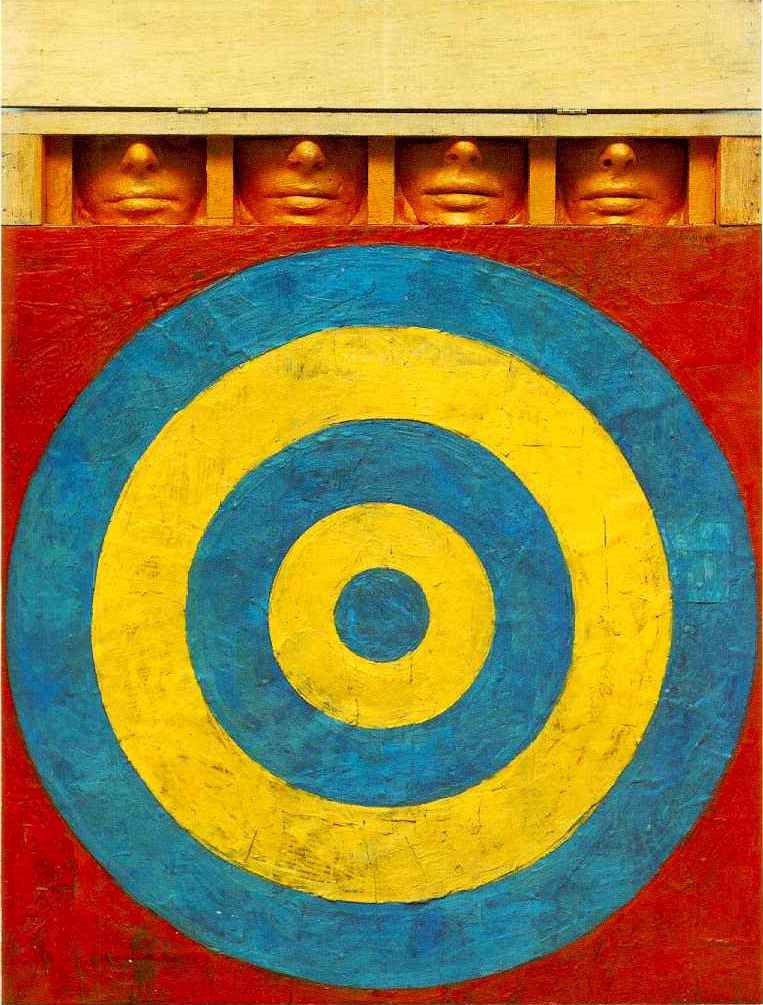

Morgan Meis: When you say that Johns’s work confronted you with a new way of seeing and thinking, are you talking about things like the target and flag paintings and the way that, say, one of his targets is both an object (a target) and a painting of that object? Or was there something else?

Roberta Bernstein: My trust in my perceptions was shaken up. This happened with the flags and targets that initially looked like the objects themselves and then became something else when looking at their surfaces, and also with the sculpture. I remember looking at a Sculp-metal light bulb and finding it hard to see it as anything other than a light bulb, and this especially happened with the Painted Bronzes of ale cans and brushes in a coffee can. What I remember being most struck by was Painting with Two Balls (1960) with its panels pried open by two small balls revealing the wall behind it.

The understanding of a painting as a real object occupying space was so vividly conveyed and made me think about art in a new way. It also made me question how I perceived the world–was I really looking, how was my mind affecting what I was experiencing? I was challenged to see and think in a new way. This quality of Johns’s work has remained for me a central aspect of my engagement with it.

Morgan Meis: That’s the philosophical side of Johns’s work, which it seems to me is especially prominent in the earlier decades of his career. Do you think something significant changed about his work after the iconic days of the flags, targets, beer can sculptures, etc.?

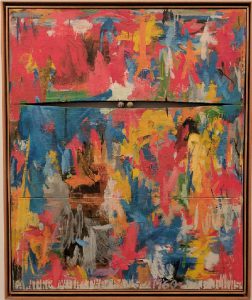

Roberta Bernstein: Johns’s concerns with perception remain at the core of his work. In 1961, the year of his break-up with Rauschenberg, the work changes. Ambiguity encompasses emotional states (In Memory of My Feelings, No, Painting Bitten by a Man). Imagery is no longer only singular or serial like the earlier iconic works, space is more expressive. Things break down and are cropped at the borders, objects and imprints, and then casts of body parts are combined in works with multiple elements. From the sixties on, Johns seeks new directions (as in the crosshatching abstractions), the layered ‘trompe l’oeil’ spaces (Racing Thoughts), the Catenaries (Bridge) and the later tracings (Regrets).

Morgan Meis: It makes sense to me that you say perception is still at the core of Johns’s work. But it used to be the fashion to think of Johns and the “perceptual challenges” in his work to be either a form of Neo-Dada (basically anti-art) or as an especially philosophical form of Pop (taking up everyday imagery into “high art”). I’ve always suspected that his work since the 60’s shows that neither of those labels really capture what he’s been doing. I wonder what your take is, especially in relation to Dada and Pop.

Roberta Bernstein: I agree that it is not about Neo-Dada or Pop. Johns’s interest in perception has to do with psychological issues. He is fascinated by the way the mind works (in relation to life and art, and it is this aspect of Duchamp’s work that he is most interested in) and the way meaning is formed. How do the senses interpret the world and make meaning of it. Ambiguity and uncertainty are inherent in this process for Johns.

Morgan Meis: I’m struck that you say Johns is fascinated by how the mind works in relation to “life and art.” Looking at the earlier works, a person could be forgiven for thinking that it was a mostly cerebral exercise, that Johns was playing different kinds of philosophical games about what makes an object a piece of art and what kinds of objects (numbers, letters, etc.) can be works of art. But somehow, with the later work, it seems that Johns was always after something more, that he was trying to figure out basic questions about how to be a person, how to see the world properly, even how to live life. Do you have that same impression, or am I going too far?

Roberta Bernstein: I agree. I don’t think you’re going too far. It is never strictly about a cerebral exercise for Johns. Seeing that a painting is made of pieces of wood with a canvas stretched over it and covered in paint and collage (as in Canvas) is about how to see without assumptions and habits getting in the way. Opening the mind to change. Also always concerned with how to “awaken the senses” and make a painting that engages the eye and mind.

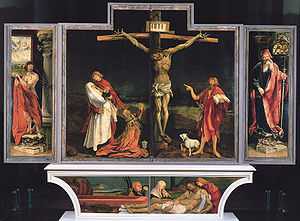

MM: I know that Johns started playing around with images from the history of painting at least since the 1980s. He’s made a number of works that reference Matthias Grunewald’s Altarpiece, for instance. I’m sure you know many more examples. Is this Johns being playful with images from the history of art, or is there something of actual religious/spiritual significance going on here?

RB: I think Johns was first and foremost struck by the Isenheim Altarpiece as a brilliant painting, but when it came to choosing to incorporate tracings of details, I believe he was very purposely selective of which ones to use – both their visual power and meaning, including religious/spiritual meaning. The theme of the Resurrection panel–transcendence, life after death–as well as the imagery of the outstretched arms of Jesus in a target-like circle of color and light must have caught his eye because of the similarity to his arms in circles. The soldier figure in the lower left corner is an amazing image–Johns described this soldier as having “collapsed in awe.”

He has said that by tracing, he was searching for the structure beneath the imagery to see how much meaning it could still convey. Johns’s art always explores how images create meaning. In this case, he was using religious imagery. Johns is not religious, as in practicing religion, but rather is grappling with the large questions about life and death that religions try to answer. The religious imagery that he adapts from Grunewald–it is found in the Seasons prints and drawings as well–is one way for him to incorporate those issues into his work.

MM: I get what you’re saying. I think the idea of playing with the relationship between image and meaning is pretty easy to grasp with images as intense as those found in the Isenheim Altarpiece. But what about more seemingly mundane, inherently “un-meaningful” images like the flagstone patterns Johns has been using for many decades now. Do you have a sense for what the relationship between image and meaning is there?

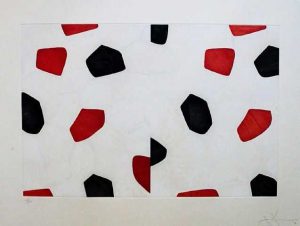

RB: Johns sometimes chose “unmeaningful” images purposely. The flagstones fit somewhat into this category. He saw them as a kind of street art that had no real meaning except in the idea of the simulation of something (i.e., that the painting of stones he saw on a wall in Harlem driving by was a painting of a wall on a wall). This applies too to the crosshatchings which he saw painted on a car–how can a meaningless “design” contain meaning. He then manipulates the image and attaches words (titles) and interjects marks and imprints that invite interpretation.

MM: So, is Johns interested in making paintings and other works of art that show us how meaning works, that catch meaning “in the act,” as it were, or more in deconstructing meaning? I guess the question is whether Johns believes in meaning or not. Is he pulling the rug out from under us or just showing us exactly how the rug is situated?

RB: I would say, the latter. I don’t think of his art as deconstructing meaning or not believing in meaning. He is, I think, struggling with (and also fascinated by) the impossibility of fixing meaning or meanings. He’s more interested in how the mind (and most specifically, given that he’s a painter, through seeing) constructs meaning. He read many books on the psychology of perception and articles when he read Scientific American regularly earlier in his career.

MM: Okay, last question. You’ve spent a fair portion of your life studying Johns, thinking about and looking at his work. Do you think this has actually made your life different than it would have been otherwise. I’m wondering, I guess, whether there is a specific character or mood or flavor to a life lived with the art of Jasper Johns.

RB: It’s a life lived with Jasper Johns, the person, as well as with Jasper Johns’s art. I haven’t thought about this before. I think both knowing him and my involvement with his art has enriched my life, given it a kind of focus too, which is deeply part of my identity. He is a complex man and his art is challenging–certainly it has been challenging for me to write about it. I have widened my own knowledge by pursuing the wide range of cultural allusions in his work (artists, writers, poets, Freud, Zen, Cage, Cunningham, etc.). I don’t know if I can pin down a mood or flavor. I have a very different personality–he would say I’m optimistic and he is pessimistic. I’m an open person, he’s defended. Because I have the sense that you are a Motown person (and now live in Motown), I will end with the reference to a Four Tops song: “Loving him has made my life sweeter than ever…”