Alexander Calder in Public and Private

Jed Perl in conversation with Morgan Meis

The two-volume biography of Alexander Calder, by Jed Perl, is an important art world event. Calder’s earlier career was covered in Calder: The Conquest of Time: The Early Years: 1898-1940 – and was the subject of an earlier discussion in The Easel between Jed Perl and Morgan Meis (here).

Perl’s second volume – Calder: The Conquest of Space: The Later Years: 1940-1976 – has been described by Atlantic magazine as a “passionate, erudite, and scrupulously researched reckoning with one of the 20th century’s most exciting artists.” It tracks a shift in Calder’s art away from his famous mobiles toward much larger works – the stabiles. These are mostly in metal and often were designed for public locations. A key challenge for Perl in Volume 2 was to arrive at an overall assessment of Calder’s work, its influence on other important artists of the 20th century, and where Calder sits – if at all – in the Modernist tradition.

Alexander Calder, Portrait (1964)

Morgan Meis: Reading your second volume, I got a feeling that sometimes you struggled – as I think everyone has struggled – with where to place Calder in art history. Do you feel you reached a conclusion on that?

Jed Perl: Calder isn’t easy to place. Ultimately that’s the measure of his greatness. Many people have struggled with the question of Calder’s relationship with Surrealism. Calder and some close friends, like Miró and Masson, all insisted that they were at odds with Surrealism. What was important for them, and certainly for Calder, was being in an atmosphere and ambience of ideas, theories and experiments — people doing this or that. Calder, like Miró and Masson, was nourished by the Surrealist environment; sometimes, they contributed to it, at other times they opposed it. There was a complex and dynamic process going on. Neither Miró, Masson nor Calder wanted to be pinned down or labelled by André Breton, the ringleader of the Surrealists. Geniuses are nurtured in very mysterious ways. There are so many influences that were more important to Calder than whatever he absorbed from the Surrealists. Calder was deeply influenced by Bosch’s great triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights. He was immensely interested in architecture and architectural forms, both ancient and modern.

MM I want to get to architecture but let’s stay for a minute with this issue you are describing. As much as someone like Miró (for instance) is more complex as an artist than the term Surrealism can ever fully do justice to, I don’t feel especially nervous calling Miró a Surrealist.

JP: There are letters written by Miró in which he is very, very skeptical about the Surrealists.

MM: OK, but you could say that part of the definition of being a Surrealist is claiming that you’re not a Surrealist!

JP: Well yes, it is complicated.

MM: Let me ask it a different way. Is there a way that Calder is a worse fit for the Surrealism category than other artists you have mentioned? And, if you think Surrealism is an especially poor tag for Calder, why?

JP: There is a psychological dimension to Calder’s relationship with Surrealism and some of the other “isms” of modern art. Calder came from a family of artists. Both his parents were artists – Calder’s father was a well-known sculptor who specialized in public monuments – and as a young man and a young artist he was used to having his artist parents tell he what he should and shouldn’t do. Perhaps this led him, as a mature artist, to elude anybody else’s definition of what he was doing. His parents were incredibly nurturing, though. They gave him his strength and his energy – and that strength became for him a spirit of resistance. Calder didn’t ever want to be constrained by any dogma. You see that in the later work. He knows by then that he’s been typecast as an abstract artist, whatever that may be, so he returns to a more explicit embrace of images of men, women, and animals.

It’s worth remembering that one of the artists he admired most was Paul Klee. Whenever he would list his favourite artists, Klee was always there. Klee is, like Calder, a difficult-to-categorize figure. Some people say he’s a figurative artist, and in some ways he is, but there are many, many works by Klee that would be called purely abstract.

The chapter in the second volume, where I talk about symbolism, is very important. In the last few years I have come to believe that what we call Modernism may be more usefully called Symbolism – the movement that began with figures like Baudelaire, Gauguin, and Redon in the nineteenth century. Renaissance artists and theorists spoke of a painting or a sculpture as a mirror of the world or a window onto the world. The Symbolists rejected that idea. They believed that the work of art is a personal symbolic construction, which can have representational elements or abstract elements – or a combination of the two. I think this helps to explain why artists including Picasso or Matisse felt free to move back and forth between greater or lesser degrees of representation. Whatever they created was a kind of symbolic image. The same is true of Calder. My feeling is that Modernism, at least as defined by Clement Greenberg as a purification of a medium, has very little to do with the achievements of Brancusi, Picasso, Matisse, Miró, or Calder. As for Surrealism, I see it as a form of Symbolism.

MM: I like that thought. Reading your book, I started to think that to understand Calder’s work in this Symbolist way you’re talking about, it’s less important to categorize him and more important just to get a sense of his approach to life in general, his life-world, his attitude, his mood, his feeling. Those are the kind of words that Baudelaire, for example, loved to use when doing art criticism. For Calder, can we understand the mood he was trying to create in his art by understanding more about the world he lived in?

JP: Let’s stay with his art for a minute. I think that whenever he went into the studio he wanted to make something that would hold you in some way – an object, as he said, that would be new in the world, that would be unexpected, that would beguile and bewilder in some way.

How does that connect with some broader feeling for life? I do think there is something to the idea that both he and his wife, Louisa, were creatures of the 1920s, of that time before the Depression, when there was still a spirit of optimism in the world, when people still believed in the freedom of the imagination.

The two World Wars were a kind of one-two punch. There are memoirs by people who were already adults before World War I, and they speak about the pre-World War I period as if it were a kind of paradise. The period between the two World Wars was a time when people were somewhat disabused of such notions but not as disabused as they would be after Hitler. I think in that interwar period there’s something of a beguiling quality to the world – the world still seems to be at play. You feel that in everything from a wonderful new dance step to some idea about the fourth or fifth dimension. Sandy and Louisa carried that worldview into the postwar years – and really to the end of their lives. I do think you feel in Calder’s work that sense of possibility. Unlike Miró or Picasso, he’s not committed to the rectangle, to the flat, two-dimensional surface. It’s not that his work doesn’t have limits, but he doesn’t have those kinds of limits.

MM: You called the first volume The Conquest of Time, which relates more to this period in the 1920s that you’re saying really shaped him. Then in the second volume we get to The Conquest of Space. Does this move from ‘time’ to ‘space’ reflect a settling down? Is that why Calder transitions from the mobiles to the stabiles?

Alexander Calder, Spirale (1958)

JP: Initially, I resisted publishing a biography in two volumes. (Eventually it became obvious that there would be too many words and images to be contained in one volume!) I originally wanted readers to experience the entire story as a single arc. A lot of what Calder does in the second volume, a lot of the monumental sculptures, are works he dreamed of in the 1930s. He’d always had the ambition to do very large objects. I believe that the insistent simplification that you encounter in a lot of the stabiles is the result of a process of trial and error. An early example is Spirale at UNESCO in Paris. I don’t think it’s a complete success; he was trying to incorporate in a big outdoors work forms of movement that don’t work on a monumental public scale.

In the 1960s he focused on a fulcrum with a ball bearing mechanism; this enabled him to generate a single big circular movement in some of the larger works. Some of those are very effective. I think over time Calder realized that certain kinds of subtle movement – that kind of floating, sneaky, graceful movement that we associate with the classic mobile – doesn’t work outside. If there’s a strong wind outside overly complex forms can get all tangled up; the work will lack the kind of direct graphic eloquence that you need.

So, I think some of the shift in the later years is just problem solving with these larger works. There are some very small tabletop mobiles that he does into the 1960’s that have a lot of the almost rococo intricacy of earlier stuff. Those late Crags – those strange hilly things – are pretty rococo. They have a kind of delicacy and the mobile elements aren’t actually attached; they just rest, casually, on the stable elements. You couldn’t have them in a public place – people would pick them up and walk off with them! So, the work always involves transformations but also a kind of flow-through – a kind of consistency.

Alexander Calder, Crag with white flower and white discs (1974)

One of the things I love about Calder is the variety of the work that he does. I adore Morandi, but I can’t imagine writing a couple of hundred pages about Morandi. I’m not saying anything against Morandi, but there’s too little variation in his life or his art to sustain a book of some length. He lived in one place his whole life, with his sisters in an apartment. There are variations in his work but I couldn’t write more than a certain amount about it…

MM: Morandi added one brown bottle to the still lifes he painted in 1932. I will now discuss this brown bottle for the next twenty-five pages!

JP: Yeah, so part of what made Calder a great biographical project is the variety – the big projects, and the friendships. Calder loved the communal nature of a lot of this work. You have a friend like Mathias Goeritz in Mexico, who had big ideas and was getting people involved in Calder’s projects. Calder absolutely wanted to be the director and make the decisions, but he loved the circle of people with whom he engaged. There’s Giovanni Carandente in Italy; Carandente, a curator and critic and a very close friend, instigated two very important projects, the stabile Teodelapio in Spoleto and what Calder called his “ballet without dancers,” Work in Progress, mounted at the Rome Opera House in 1968. Many of the major late works are grounded in a place, an occasion, a community. Any artist who does public projects that have a lasting impact feels that sense of community. Calder had many close friends who were architects and they, like he, understood that the best projects and commissions involved a meaningful connection with the people who were going to live with those works.

MM: That leads to another question. You could say that as he moves to a grander scale there is more of a dialogue with architecture, since so many of the big sculptures are placed next to buildings. Is the dialogue with architecture the main thrust of the later work?

Alexander Calder, La Grande Vitesse (1969)

JP: Well, that’s the reason I opened Volume 2 with a story about how Calder managed to get La Grande vitesse mounted in a public plaza in Grand Rapids in 1969. One of the things that people have forgotten is that while today it is a cliché to have pieces of modern art in front of every big public building, there was a struggle for this kind of stuff back then. For example, take the Lincoln Center stabile – the Parks Commissioner in New York absolutely did not want an abstract sculpture at Lincoln Center in the 1960’s. It’s now half a century later and I think we’ve forgotten that there were these struggles.

Calder had an extraordinary sense of size and scale – not just literal size and scale – but the imaginative possibilities that could be generated by a particular size and scale. He realized that a certain kind of funkiness or craziness or delicacy was possible at a certain scale but wouldn’t necessarily work on a larger scale. But then he still manages to throw these curve balls in this biggest works. Two good examples are the enigmatic forms of Flamingo in Chicago and Stegosaurus in Hartford. These works are part anthropomorphic, part architectural – and the tension between those dissonant forces gives the work its mysterious power. Calder is always keeping you actively engaged.

Alexander Calder, Flamingo (1974)

MM: That reminds me of a feeling I had regarding Flamingo. The one that’s in Chicago …

JP: … which is surrounded by the three buildings by Mies van der Rohe…

MM: What’s Calder doing there? I mean, you could say that Calder’s Flamingo is making fun of Mies’s buildings. Do you see it that way at all?

JP: No. I would compare it to a piano concerto. Flamingo is the soloist engaged in a dynamic relationship with the orchestra. Have you been there?

MM: Yes. My initial feeling was that Calder didn’t like the Mies buildings and was trying to fix them a bit with Flamingo. But perhaps that’s just me.

JP: I would return to my analogy of the concerto form. The orchestra – Mies’s buildings – is doing one thing while the piano does another. I think Calder was thrilled by the possibility of that kind of dialogue. In terms of the idea of a large object in an urban space, I think that Federal Center in Chicago is the one place where, for him, everything came together. These plazas in urban places so often become dead spaces. Urban planners talk about that a lot – people go there and eat a sandwich at lunch, but it’s not dynamically a part of the city. That’s true of the Picasso sculpture that’s a few blocks away. I would say that the Picasso is more interesting in person than it looks in reproduction, but nevertheless it’s pretty much just stuck in front of a building. There’s something deadening about the Picasso’s relationship with the city.

One of the amazing things about Flamingo is that it’s set in a plaza that people are crisscrossing throughout the day, so that men and women are moving around it, coming at it from different angles, in morning, noon, and night. What you might call this urban dance helps to bring Flamingo alive. I think it’s a soloist, you know, dancing with Mies’s three massive “orchestral” blocks. There’s the post office, which is one story, the building next to it and the building across the street. Flamingo knits them all together. The Mies buildings are an incredible group of buildings – dark, saturnine, ceremonial — and Flamingo, with its lighter spirit, brings the whole ensemble to life. It’s an absolutely wonderful work.

MM: If that’s one example of Calder’s approach to dealing with big public spaces and moving his work into dialogue with Modernist architecture, can you think of an example where he fails to do that successfully? You mentioned some more and less successful works. What comes to mind?

Alexander Calder, Teodelapio (1962)

JP: Well, some of the early ones – Spirale at UNESCO, which I don’t think works. There’s a kind of delicacy about Spirale and the mobile elements, but you’re unable to home in on what Calder’s doing. The gesture that the forms in Spirale make is too delicate to register in a big, urban space. It might register in a rural space, like a clearing with trees or something, but it doesn’t register with the hardness of the urban environment. (It should be added that Spirale is no longer situated in the spot for which Calder designed it.) Stegosaurus in Hartford is a wonderful sculpture done precisely for that place. It’s next to a more traditional building and it doesn’t come to life. Teodelapio in Spoleto is wonderful. But what’s around it – the train station – isn’t up to it.

When you’re dealing with large public works, it’s like talking about the movies or Broadway productions. There are so many things that have to come together for a piece like this to work. Calder was disappointed by the size of Le Guichet at Lincoln Center; he thought it was too small. I guess he was thinking about it against the side of the Opera House; but when you’re approaching the Vivian Beaumont Theater, I think Le Guichet works quite well. But he felt it wasn’t big enough.

Alexander Calder, Le Guichet (1963)

So, you know, there are all these crazy considerations. It’s like the problem with architecture, the landscape around changes. You can put something in an area that’s less developed and then it becomes more developed in a way that doesn’t really do the architecture justice.

So, large public things don’t work out all that well all the time. One I reproduced in the book is called Horizontal. It’s now in front of the Pompidou Center in Paris and works very well there. It’s a very communal space where there’s always a lot of action. With its horizontal bar with colored elements hanging off it, Horizontal has a kind of festive quality. It also has a stalwart power that I think holds the space.

Alexander Calder, Horizontal (1974)

MM: We’re talking a lot about these monumental stabiles and other later works. Nonetheless, Calder will always be associated in the public imagination with the mobiles. Is this fair?

JP: I see Calder as a very large figure. It’s always the case with such figures that you can choose to perceive them from a certain angle at a certain time. You have just written a book about Rubens (Morgan Meis’ new book, The Drunken Silenus – Ed.) that emphasizes aspects of Rubens that are probably not what people associate with Rubens. Or take Michelangelo. I’ve heard people say that it’s the architecture that is the very greatest aspect of Michelangelo. But for most people that’s not what comes to mind; they would think of a painting or a sculpture.

The mobile is the signal contribution that Calder made to the art of his century. But artists are seen in different ways at different times. One of the things that I found interesting when I was working on volume two was that when younger artists were looking at him in the 1960s, it was the stabiles that excited them. So, what you’re talking about is really the history of taste and the history of ideas. Look at a figure like James Joyce. What aspects of Joyce are people interested in now? Are they interested in Finnegans Wake? – I don’t know. Things shift. There’s a lot in Calder and I think people may see different things at different times.

MM: Okay, but is it fair to associate the word “play” more with the mobiles and the word “serious” more with the stabiles?

JP: Well, I think play is serious and true seriousness is a form of play. And there are different kinds of play – there are mobiles where Calder is saying ‘let’s just be crazy today, you know, I’m just gonna put in things you never thought I could put in a mobile’.

He’s an artist of many moods, which is one of the things I like about him. I can find something rather grinding and grim about the repetitiveness of some of the American Abstract Expressionists. Take Rothko. He did some absolutely beautiful paintings, mostly, I think, between 1948 and 1950 or maybe 1951. But to keep to the same format, year after year, I find that strange and somehow off-putting. One of the things I like about Calder is that he goes in lots of different directions. Sometimes he seems to be saying, ‘what the hell, I’m going to try this.’ Or, after a phase of being a hard-ass abstractionist, he’ll seem to be thinking, ‘Oh, I think I’m going to do something that mixes it up a little more’.

You see this in Picasso – and in Matisse. I think it’s a response to the variety of our experience in the world. There are days when you get up and feel serious, ready to do something serious, but there are other days when you’re in a different kind of mood. Calder was sensitive to those subtleties. At the same time, obviously, a creative person pursues certain lines of thinking.

Alexander Calder, El Sol Rojo (1968)

I comment about El Sol Rojo – the great stabile in Mexico City with a red disk mounted on a tripod – that it feels minimalist; it’s certainly among the most minimalist of the stabiles. Mathias Goeritz, the man who commissioned El Sol Rojo, was a sculptor and an architect and is often described as a kind of proto-minimalist. Calder was familiar with things Goeritz had done. I think in creating the minimalist imagery of El Sol Rojo, Calder was entering into a dialogue with Goeritz, thinking, ‘Oh, okay, I’m going to see how much I can do with how little.’ In contrast, Trois disques, the enormous object he created for Expo 67 in Montreal around the same time – has the elaborate energy of a high Gothic cathedral, with towers and turrets and flying buttresses.

Alexander Calder, Trois disques (1967)

I don’t think it’s impossible that in Trois disques Calder was thinking about Montreal as part of the visual history of France. He was always playing with the possibilities. But you have to understand play in the sense that somebody like Nabokov talked about play – everything is play. Thinking back to the 1920s, when Calder was first living in Paris, Joyce was writing Finnegans Wake, which involves playing with the entire history of language. It’s hard for us to grasp the seriousness of play because, frankly, Hitler and Stalin beat it out of the world. I do believe that. This is one of the problems some of the Abstract Expressionists faced when looking at Calder. Even when they looked at his work closely, they sometimes found it difficult to appreciate. I think part of the issue here is that Calder’s attitudes had been formed before the Depression and World War II, while the Abstract Expressionists were shaped by those terrifying events and their aftermath. In their aftermath, play became a dirty word, but for Calder it was what he did, it was the matter of life.

MM: Yeah, and I think you explain that well over the two volumes. So, is what we are discussing here the oscillation between different forms of play?

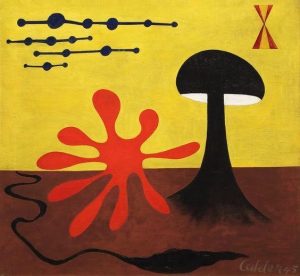

Alexander Calder, Untitled (1945)

JP: Yes, play can be serious. An example is the set design that Calder did for Socrate, a chamber opera by Erik Satie, in the second half of the 1930s. Socrate deals with the death of Socrates, and so Calder gives his work here a very cool, austere quality. In the 1940s Calder did a long series of paintings in which he let loose with his craziest, weirdest fantasies. I’ve sometimes wondered whether if I saw one of those really wacky paintings unsigned in a thrift shop, would I buy it? You know what I mean – they are really bizarre, completely insane paintings. Calder indulges in some of the same over-the-top playfulness in his late Critters. But when it came to the largest public works, he felt that what was required was a different kind of decorum – a different kind of play, if you will.

Alexander Calder, Critter without Arms (1974)

MM: You think he made those later Crags and Critters almost to let that energy out while he was doing his other sorts of heavier public works?

Alexander Calder, Mountains and Clouds (1986)

JP: I think that’s part of it. I also think – and I think this about the late Picasso too – that he was influenced by the youthquake of the late 60s, changes in sexual behavior, the opening up of certain kinds of experience. I think some of what was happening in the 60s reminded Calder and Picasso of some of the craziness of their youth. Like some of the late Picasso lovers and erotic prints, I think that the Critters and Crags are works by an older person feeling that let-loose spirit a little bit.

The last work Calder dealt with, the day before he died, was the Mountains and Clouds in Washington. This is a very austere work, which was done a couple of years after the utterly un-or even anti-austere Critters and Crags. It’s a shame, you know, that the Calder most people see in Washington is the mobile in the National Gallery, which is a failure. It was not fabricated by him according to his own methods and it’s really a dud, I think. The great work in Washington is Mountains and Clouds in the Hart Senate office building. You can just walk in, actually, but not many people see it. And that is an extraordinary late achievement. But again, in a kind of austere mode; it makes you think of Richard Serra.

MM: Here is my closing question. You have worked on these two volumes for a long time – a decade. They are now done and out. Do you feel like this confrontation with Calder has changed you at all, your sense of art, your taste?

JP: I would say it has strengthened the feeling I’ve always had that art is both totally in the world and completely in a world of its own. I’ve been trying to see this man in the round, both as a man totally engaged with the hurly-burly of life and as an individual creator pursuing his own private passions. Working on the biography has increased my sensitivity to all the ways in which the life of art and the life of the world do and do not touch. So yes, I would say it’s magnified those things for me.

I would also say that I’ve been writing this biography over a decade during which we have seen the rise of political correctness and a kind of insistence on constantly situating the arts (not just the visual arts, but the literary arts, every form of art) in a matrix of gender and race and sexual and political concerns. I worry that there’s less and less willingness to see creative individuals as independent agents and works of art as having a freestanding value. Part of what I admire about Calder is that he lived very much in the world even as he pursued a creative life that ran parallel to the world.

I don’t know if you noticed, but there’s a long endnote in this volume about a young art historian who has written a lot about Calder and insists on seeing him – almost burying him – in this kind of socio-political matrix. I agree that it’s important to situate artists in their time and place. But it’s also important to remember that an artistic vocation has its own life and logic. Calder was probably happiest when he was working alone in his studio. It was only by going deep into his own thoughts and feelings that he was able to show the wide world what he wanted men and women to see.

Calder: The Conquest of Space: The Later Years: 1940-1976 is published by Alfred A. Knopf.