Irving Penn: Photographism @Pace

Richard Woodward | Collector Daily | 2nd February 2021

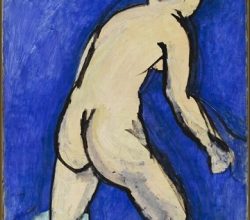

From quite early, Penn showed that commercial photography could merge into art. Clearly, his early training to be a painter shaped his modernist aesthetic. But what magic did he bring to photography? An ability to balance “allurement with revulsion”? The graphic quality of many of his images? Perhaps the timelessness of his images reflects the lessons he derived from great painting and sculpture – “simplicity, rigor, wit, elegance”.