Night Swimmers

From a Renaissance Madonna to an Indian abstractionist, Rachel Spence takes a voyage through geometry, mysticism and the female figure

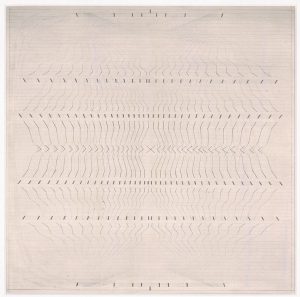

Nasreen Mohamedi untitled (1975) Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

Rachel Spence, March 7, 2017

If you love art, the possibility of revelation is always present. In 2007, while I was living in Italy, I was rocked to my core when I came upon Antonello da Messina’s “L’Annunziata” in the Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo. A solemn face, shrouded in a lapis-blue cloak, one hand raised above her wooden lectern as she gazes at the angel only she can see. Behind her, a vault of black space.

Although she was painted in 1476, she is radically different from most of the Annunciation scenes of that era. This is no demure maid humbled by divine presence. Rather she seems to be asking the Archangel to give her a moment to consider her response to his proposition. Is this a woman about to say “no”?

When does a life bend towards freedom. grasp its direction?[1]

L’Annunziata: Antonella da Messina, Galleria Regionale della Sicilia

Antonello’s Madonna whispered that all of us can shape our own destiny. You think she became the mother of Christ? Wept over her Son’s corpse beneath the Cross? Perhaps. But somewhere, that painting also hints at a woman who chose a different path. Celibacy over motherhood. Solitude over family. Presence over absence. Most importantly, abstraction as a truth more resonant than the figure. Few Madonnas in history have been painted with such pared-down simplicity of form as L’Annunziata. If you narrow your eyes, she is as uncluttered as a geometric painting by Ellsworth Kelly.

I listened to the message she was whispering. Within a few years, I left Italy and returned to the UK. I started to write poetry again. Curiously, for all that I was confused, frail, and uncertain, my commissions grew more interesting. And so it was that, on a humid January evening in 2013, I found myself in the Kiran Nadar museum in New Delhi standing in front of the work of Nasreen Mohamedi.

The inauguration of Mohamedi’s exhibition is a buoyant affair. Throngs of revellers nibble at canapes and sip from wine glasses. So vibrant is the party, I am barely aware of the art. Furthermore, the exhibition seems designed not to call attention to itself. Weary of the hubbub, I drift over to the gallery. Let my eye wander over work so reticent it is barely present. Drawings and photographs whose diminutive size belies the grandiosity of so much contemporary art. A monochrome palette of black, white and grey. Slowly, the images start to call to me like music heard beyond a closed door. Abstract lines are sketched in ink and pencil with such meticulous control their density thins and thickens as if mapping waves of sound. Whisper-quiet rhythms.

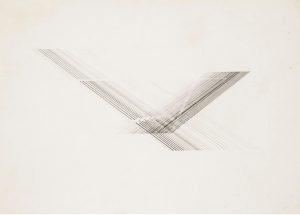

N Mohamedi untitled (1970) Glenbarra Art Museum

There are two hundred works in all and after twenty of them I am hypnotised. These are images that shift your world on its axis. Never again will I look at moonlight hitting water in an ellipse or a grid of scaffolding on an urban tenement, without thinking Nasreen.

Why has nobody told me about Nasreen Mohamedi? Modern art in India, I had believed, was chiefly a narrative about painting. At its centre were those who had founded the Progressive Artists Group in 1947. Based in Bombay, these painters – who included figures such as FN Souza and MF Husain – had very different styles but as well as drawing on Indian origins they also shared an inspiration from international figurative modern painting movements such as Expressionism, Cubism and Surrealism.

Mohamedi came from somewhere else. A place that was essentially invisible, inward, profoundly mystical. Her images whispered of the latent structures that underpinned the material world; uncanny frequencies into which only the most sensitive ears could tune.

N Mohamedi untitled (1975) Sonia Ballaney / Vadehra Art Gallery

Nature is so true.

Such truth in her silence.

If only we would listen to her intricacies.

Then there is no difference in sound and vision[2]

“If this is where I must look for you, this is where I’ll find you.” [3]

And so I embarked on the beginning of a journey into the eye and mind of an artist who would change my way of looking, and being, in the world.

Nasreen Mohamedi emerged from a lineage that both fed into and departed from that of the Indian figurative school. Born in Karachi – then part of British India later to become part of Pakistan – in 1937, she grew up in an affluent Muslim family. With ancestors in the Arab world, they were part of a Shiite community that championed female education. As a young woman, she was a cosmpolitan, studying at St Martin’s School of Art in London and then at a print atelier in Paris as well as travelling to Turkey, Iran and Bahrain. In 1958, she settled in Bombay with a community of artists whose creative hub was the Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute.

Here, she met the painter Vasudeo Santu Gaitonde (V.S.) who, like Mohamedi, would pursue an abstract path that set him apart from mainstream Indian modernism. Mohamedi’s early works show an affinity with Gaitonde’s paintings. His canvases used veils of paint, often scumbled and scuffed so that they took on the faint, rubbed quality of faded wall paintings or resembled the traces of form and colour left after a painting had been laid down and peeled away.

Mohamedi’s images too gestured at some unseen, unknowable origin. Soft splashes of black ink, often laid over thin grey washes, then sharpened with stronger, more calligraphic marks, her images from the early 1960s speak of an artist struggling to break through to a reality that eluded orthodox ways of seeing.

For her, as with Gaitonde, painting was a response to interiority. Or rather, to exteriority once it had been processed through an inner sensibility. This process was elaborated by Wassily Kandinsky in his landmark text Concerning the Spiritual in Art. The Russian divided paintings into three stages: impressions, improvisations and compositions. The first was the artist’s subjective response to an external image such as the landscape. As he or she processed it through the unconscious, it transformed into an improvisation and then took its final form as a composition. Kandinsky was a powerful influence on Mohamedi who noted in her diary: “Again I am reassured by Kandinsky – the need to take from an outer environment and bring it an inner necessity.” [4]

Acute observation of the natural world is a central tenet of Zen Buddhism, to which both Gaitonde and Mohamedi were drawn. Gaitonde once wrote that his study of Zen helped him to “to understand nature, and my paintings are nothing else but the reflection of nature”[5]. Both he and Mohamedi loved to contemplate the sea. He was often to be found sitting alone staring at the waterfront in Bombay, contemplating the shimmering matrix of the waves. Mohamedi would visit her family home in Kihim, near Bombay, and walk by the ocean for hours. After once such stroll, she wrote: “Lines, subtle, winding tremors/Orange shapes/Crystal sparks/An illuminated dark expanse/Notes on water”.[6]

By 1972, Mohamedi had settled in Baroda, Gujurat, where she taught drawing at the Faculty of Fine Art at the Maharaja Sayajirao University. All realism had been evacuated from her own images. Paint, canvas and easel had also been left behind. Driven by what she described in her diaries as the need to extract “the maximum out of the minimum”, she worked in pen, ink and pencil on sheets of paper. Drawings from the 1970s show how she maintained a breathtaking command of line and tone. Sheet after sheet of impeccable matrices assembled from diagonals, chevrons, horizontals and verticals that march, swoop, glide and zig-zag across the surface as if they are musical scores for mystical symphonies, or the patterns made by the wind on desert sands and ocean prairies. There, gone, then, now. Transient and eternal in their endless erasure and repetition.

Certainly, she was aided by her precision tools which included a technical drawing pen with changeable nibs, ruler, set square, T square, protractor and compass. But only a mind devoted to the internal gaze could conjure Mohamedi’s intensity of practice.

That gaze drew its energy from both east and western influences. Mohamedi absorbed the lessons of western abstractionists such as Kandinsky, Klee, Mondrian and Malevich, all of whom worked out of a spiritual impulse towards expressing truths that transcended the material world. Yet, as I’ve said, Zen Buddhism was also a constant teacher. As was Sufism. The mystical strand of Islam, Sufism enjoins its followers to pare down their lives and empty their minds. In the words of the Sufi poet Yunus Emre: “Being destitute I become affluent: the universe became mine”.[7]

Mohamedi was renowned for her personal austerity. Roobina Karode, who was her student and friend and who curated a retrospective devoted to Mohamedi at Madrid’s Reina Sofia museum in 2015, recalls Mohamedi’s apartment at Baroda. “Uncluttered and sparse, the studio had the ambience of a Sufi haven, the only furnishings a low drafting table and a low hanging lamp in the centre of the room.” Mohamedi was exceptionally clean and tidy, mopping her floor several times a day. “The daily rituals of cleansing before sitting down to work were as mandatory for her as rituals of ablution before the offering of prayers,” continues Karode.[8] The act of decluttering her surroundings prepared her to receive the illumination she needed in order to draw.

The empty mind receives/drain it, squeeze the dirt… hard/so that it receives the sun with a flash [9]

Solitude and silence were necessities. “Solitude + strength / without compromise /A freedom.”[10] Sitting cross-legged on a low stool, Mohamedi would work through the night. Although she had close relationships, the impression given by Karode, and others who knew her, is of an essentially solitary, almost ascetic figure, devoted to her practice.

Always, she scribbled lists of numbers and geometric diagrams, interspersed with poetic phrases to herself, as if tracking her way towards a clarity that was mathematical, literary and imaginary. Grounded in a quest for a reason so pure it tipped over into the inexplicable and uncanny. To look at some of her drawings, one pattern of pristine lines drawing the eye one way, another tugging our gaze in the other direction, light and shade balanced like opposite poles on a dynamic spectrum, is to think of the quantum physics that leaves scientists baffled by a particle’s capacity, for example, to be in two places at once.

Mohamedi died tragically young, at the age of 53. Since youth, she had been afflicted with Huntington’s disease, a cruel neuro-muscular condition which affected control of her movements yet left her able to employ her drawing hand. Works from her last decade show her leave more space empty; her geometric forms shrink and intensify, often repeating each other as they expand and contract in sequences that seem barely anchored to the centre of the page. The whites adopt a diaphanous glare; the blacks possess an inky velvetiness; the grey pencil takes on an evanescent flicker.

To look at these drawings is to feel you are witnessing a world, or a cosmos, in a state of both becoming and departure. These are visual testaments to a holy order. In the beginning, they murmur, was the Line.

Introspective, Abstract, Unwitnessed

When I left the Delhi museum on that January night back in 2013, Nasreen Mohamedi had stitched herself into the warp and weft of my interior world as tightly as the Madonna of Antonello da Messina. Both artists seemed to gesture at a different way of making art, using an economy of line and shape to conjure forms at once secular and sacred, internal and external.

Both also revealed different ways of being a woman. Mohamedi – in the way she made her art and lived her life – and the Madonna, with her ambiguous, possibly negative, gesture, suggested that a woman might renounce stereotypes of femininity. They were oblique, opaque, essentially hermetic. As if they had turned their back on the whole circus.

Without being aware of it, I started to live differently. Dressing in black and grey. Listening obsessively to Bach’s spartan suites and sonatas for violin and cello – long, linear, puritan notes which felt like sonic expressions of Mohamedi’s drawings and the Madonna’s austere lines.

For years I had had a regular meditation practice. Increasingly, I supplemented it with yoga. When I practised, the shapes my limbs made chimed with the music and images in my head. In Sanskrit, yoga means, literally, to yoke. The first unity is that between breath and movement. Then body and mind. Finally between the self and world beyond. Mohamedi, always, was involved in a search for unity. “All the forces of nature are interlinked”[11] she once wrote.

I was writing poetry with more focus than ever before. Sitting on floor cushions in my apartment, a copy of a catalogue about Mohamedi on the low table in front of me. A reproduction of Antonello’s Mary on the wall above my head. The images whispered to me of stillness. Of silence and solitude. Of an introspective gaze, abstract, unwitnessed.

“I could write of […],

of you as woman, solo

but you gesture to a faith in love and work

Reduce. Reduce. Reduce.” [12]

Antonello da Messina and Nasreen Mohamedi are separated by gender, geography and history. And yet, to me, they are linked, their work blinking out cryptic, metaphysical codes across chasms of time, distance and understanding.

“Madonna of triangles.

Pyramid of cloak carving a perfect V

out of the vowel of black. At a time, when

geometry was God’s own arithmetic,

perspective set you free as a night swimmer”. [13]

The Ground Beneath My Feet

You cannot live in Italy and write about art for nearly a decade, as I did, without becoming aware of the power of geometry.

My home town was Venice. Although there are Renaissance and Baroque buildings, the city’s architectural imprint is medieval. What this means, on an architectural level, is that its builders and stonemasons did not work according to the classical Greek principles.

Instead, they constructed more informally. Forget equilibrium, symmetry, complex declensions of Greek columns, echoing spaces, pale, unadorned skins of marble. Venetian architecture is a hymn to the dainty, exotic and decorative. Her creators loved nothing more than to carve a gargoyle or chisel a spiral, paint a fresco, add a disc of coloured porphry, lay a façade of striped pink and white bricks, or mould a window frame into the shape of a petal.

Photo: Wolfgang Moroder.

That jewel-bright radiance, allied to a unique topography where water and sunlight are as active and present as the stones of the streets and houses, give Venetians a sensation of permanent, sparkling, diaphanous movement. It is bewitching, delectable, architectural soul food.

But sometimes, I would awake desperate for firm ground beneath my feet. Then I would go to Florence. The city that was the template for the Italian Renaissance, home to a clutch of palaces, churches and squares constructed by Filippo Brunelleschi. The first person, or so it is said, to discover linear perspective, Brunelleschi was the heir to Plato, Euclid and Archimedes. Classical thinkers whose philosophical, mathematical, and engineering knowledge are crucially bound up with the balanced orderly spaces of ancient Greece and Rome. This was a discipline of simplicity. Minimalist, innately calm, based on mathematical ratios. It was the architecture of an age of reason.

Brunelleschi is most famous for building the majestic dome that guards Florence cathedral. But for me, his most valuable gift is the Piazza della Santissima Annunziata, the square overlooked by the eponymous church. An austere, virtually empty space flanked by raised arcades, the piazza greeted me on the first morning I woke in Italy – long before I went to Venice. I was barely 20, young, in love, and clueless about the country in which I found myself. I threw open the window of our hotel room and peered out. Breathed. Experienced for the first time the joy of nothingness. Does emptiness signify loss? Or possibility?

“Let nothing be inside of you.

Be empty: […]

When like a reed you fill with His breath,

then you’ll taste sweetness.” [14]

Venice was light, water, colour and movement. Dazzling, unpredictable – in topography, architecture and anima – wayward as a wild cat, dissonant as atonal music. Florence was the sturdy older sister. Colder, plainer, a place of open squares and rhythmic arcades. A place where you could feel your mind root into the ground of logic rather than fluctuate along rivers of emotion, grow still as the golden light creeping over the Tuscan hills. In Florence, the light stayed put. In Venice, it fractured into a mosaic of glittering splinters at the merest thread of sun.

If Venice took you to giddy, perilous heights, Florence brought you back to earth. Yet they were equally necessary for a sense of the Divine.

“I was born in harbour light,

porous, transient.

No wonder Venice spoke to me.

But I had changed by then,

in Tuscany I met Piero,

his Mary’s face blank as her pregnant belly,

an inland light made for the plainsong

of the Tuscan hills, depth not ruled

but sung, form made and unmade

until the eye learns to

let go, find unity

in anklebone and column, brow

and archivolt. [15]

Out of Chaos – Form – Silence[16]

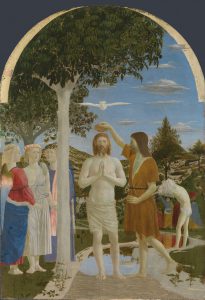

It’s possible that Antonello painted L’Annunziata in Venice. He visited the lagoon city in the mid-1470s, before returning to his birthplace, the Sicilian port city of Messina, where he died around 1479. But before reaching Venice, he almost certainly passed through Tuscany, and there saw the work of Piero della Francesca. Piero was not only an extraordinarily gifted painter he was also an accomplished mathematician who, as well as writing his own treatises, also illustrated the works of the Greek mathematician Archimedes.

More than any other paintings of the Renaissance, it was Piero’s cool, impeccable harmonies of line and curve that could make the viewer believe that Plato was right: geometric shapes were the nearest men would ever get to seeing God’s work on earth.

When Antonello painted his Virgin, he had the teaching of Piero and Brunelleschi at his fingertips. Consequently, he could set his model into deep, recessed space. Open the angle between her finger and the lectern so that you felt you could reach into the painting and grasp her hand. This is a painting in which space speaks as eloquently as solid. The air around the woman as expressive as her gaze. As tangible as her flesh. It is her painter’s understanding of geometry that gives L’Annunziata substance. It gives her three dimensions. Allowing her to literally defy her one-dimensional reality on a flat surface, it rescues her from the taint of all that is metaphorically superficial. It is the source of her dignity and grace. Wait, says that raised hand. Give me a moment. I will decide what I do with my womb.

Nasreen Mohamedi sits at her drawing table. A woman wedded to silence and solitude. She fingers her tools. Lays a set square on a sheet of paper. Reaches for her pencil. She has absorbed an expertise stretching back to Euclid and travelling on through the centuries when Islamic geometricians expanded it into a body of knowledge fit for the creation of mosques, carpets and ceramics. Abstract, repetitive, immaculate in their detail, the diagrams and designs elaborated by Islamic mathematicians acted as celebrations of God. In Islam, the Divine One cannot be shown. But he can be honoured through shapes and patterns whose perfection is itself a sign of His unerring hand.

“Thought and geometry, geometry and thought […]

thin threads into space… a pure vision of non-physical space” [17]

“To find … a unity between people” [18]

It’s often said that the measure of a great work of art is that it stands the test of time. But perhaps another criteria is that it stands the test of space. Not just then and now but also here and there. Would it be too estoric to say that Nasreen Mohamedi and Antonello da Messina are not only products of their time and place but also of each other’s? That this is the territory which Nasreen was seeking when she once enjoined herself to “See and feel primeval order”? [19]

She came from the east, he from the west, yet the geometry they share is universal. When the Roman Empire fell, so much of its knowledge would have been crushed in the rubble had not certain key classical texts been preserved in the Islamic world. For example, the great 10th- century mathematician from Baghdad, Ibrahim Ibn Sinan, translated Archimedes. Travelling through North Africa in the 12th century, the Italian mathematician Fibonacci discovered the Arabic numerals which he then introduced to the western world. Start to investigate and a myriad east-west synergies come to light; for example, the revolutionary cycle of numbers known now as the Fibonacci sequence actually originated in 6th century India.

Let’s recall too that Euclid lived and died in Alexandria, Egypt and Archimedes may have been educated there. The North African territory was part of the Greek and then Roman empires. How often do we find the borders between east and west so frail as to complicate such identities until they are barely holding?

As for me, I am still sitting on the floor. Looking. Writing. Outside my window is a world where women are still enjoined either turn themselves into objects of the gaze, or to retreat from sight as if exposure equals dishonour. Caught between the Scylla of Make Yourself Beautiful and the Charybdis of Cover Yourself Up. Still, too often, we are situated between the rock of motherhood and the hard places of spinsterhood or whoredom. But here in my room, Nasreen and Antonello – or the figure he created – quietly urge me to continue that inward turn.

“I cannot seek from without. It has to come from within.” [20]

That self-reflexive curve is, essentially, a non-objective gesture. Detaching itself from the figure – which is so often bonded with its historical and geographical moment – abstraction can take us to that state of origin which is close to rebirth. Or as Nasreen Mohamedi put it so acutely. “Out of chaos – form – silence.’ [21]

[1] Inscriptions/ Two: Movement, Dark Fields of the Republic, Adrienne Rich, WW Norton, 1995

[2]‘Diaries’, Nasreen Mohamedi, 1980?, quoted in Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved, Geeta Kapur, The Grid, Unplugged (Talwar Gallery, 2008) p.19

[3] ‘Modotti’, Midnight Salvage, Adrienne Rich, WW Norton, 1999

[4]Diaries, NM, quoted in Kapur /Reina Sofia op.cit. p12.

[5]V S Gaitonde, quoted in Polyphonic Modernisms and Gaitonde’s Interiorised Worldview, Sandhini Poddar in V S Gaitonde, Painting as Process, Painting as Life, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 2016, p28

[6] Diaries, NM, quoted in Waiting is an Intense Part of Living, Roobina Karode in Nasreen Mohamedi: Waiting is an Intense Part of Living, Museo Nacional Centro De Arte Reina Sofia, 2015.

[7] Diaries, NM, quoted in Kapur/Grid Unplugged. op cit. p8

[8] Karode /Reina Sofia, op cit p31

[9] Diaries, NM, quoted in Karode/Reina Sofia, op cit. p31

[10] Ibid p32.

[11] Diaries, NM, quoted by Rachel Spence in Less is More/Financial Times, 30 June, 2014

[12] From “For Nasreen”, in Furies, Rachel Spence, Templar Poetry 2016

[13] From “Right to Choose,” Furies Ibid

[14] From Ramadan, The Pocket Rumi. ed. Kabir Helminski, Shambhala, 2011

[15] From Antonello’s Song I Furies, Ibid

[16] Diaries NM, quoted in Kapur/Reina Sofia, op cit. p171

[17] Diaries N M Quoted in Karode/Reina Sofia op cit p43

[18] Diaries NM ibid. p44

[19] Diaries NM (ref to come)

[20] Diaries NM quoted in Karode/Reina Sofia op.cit p25

[21] ibid.