Now you’re over the sticker shock, what about the art?

In 1500, Leonardo was an artist working for hire. One of his clients was Louis XII of France. The painting he had just completed was a portrait of Jesus Christ, quite possibly a commission from the French monarch. History does not record whether the completed work met with approval but, once painted, Salvator Mundi began a rather improbable journey in and out of oblivion. A couple of decades after it was completed (and by way of royal marriages) Salvator Mundi ended up on the British Isles. For the next hundred and fifty years, the painting was in the possession of various English courts and palaces. Then, in the late 18th century, the painting disappeared from the historical record. That’s the oblivion part of the story.

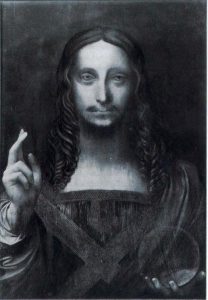

During the oblivion years, Leonardo’s painting fell on hard times. It was damaged and – in an attempt at restoration – painted over in such a way as to make Christ look like one of the dopier members of the Manson Family. The painting, no longer recognizable as a Leonardo, was sold at auction in 1904 – mentioned in a long CNN video on the piece that is here. It appeared at auction again in 1958, selling for the modest sum of forty-five British pounds (the image below is dated to that year).

It was sold again in the US in 2005 to a consortium of dealers led by Robert Simon. They got it for around $10,000. Simon, a New York fine art dealer specializing in Renaissance works, suspected it was worth much more than that, though he dared not yet dream it might be the lost Leonardo. Years of restoration work brought out the Leonardo concealed beneath the third-rate overpainting. It then sold for $75 million in 2013 and right away again for $127.5 million. Finally, just last October, Salvator Mundi was purchased by a Saudi prince (on behalf of the Louvre Abu Dhabi) for $450.3 million dollars, making it the most expensive artwork ever sold.

Salvator Mundi has proven itself to be a painting that generates one surprise after another. The latest, after the record-breaking sale, has to do with its next home. That’s to say, Salvator Mundi is a painting of Jesus Christ that will soon be on display in the UAE, a country in which the spreading of Christianity among Muslims is forbidden by law.

I, for one, find it intriguing that Salvator Mundi will spend perhaps a considerable amount of time in a Muslim country. In the ongoing debates between Muslims and Christians, the doctrine of the Trinity has always been a sticking point. Muslims hold a straightforward and laudable position. God, they say, is one and indivisible. So, let’s cut out all the nonsense about God as a Father and a Spirit and a Son. Muslims never tried to deify their prophet. Mohammed is great, but he is a man. Christians have a trickier circle to square. Christ is man. But he is also God. There is a logic to this doctrine, but it’s a logic that threatens to fall apart every time one tries to think it through too much.

What has all of this to do with Salvator Mundi, you ask. Well, in Salvator Mundi, Leonardo was making a painting, but he was also trying his hand at theology. Painting Christ as a man is easy. You just paint a man. Sure, you have to decide what color his eyes are and whether he wears a beard or not. But the theological stakes are pretty low. Not so when you paint Jesus Christ as the savior of the world. Then, you are moving your way up the Trinity, so to speak. The Christ of Salvator Mundi is Christ fully divine. He stands outside of creation, holding the earth – or at least a representation of it – in his hand.

This raises some serious painterly problems. How do you paint a man as more than a man? Plenty of painters other than Leonardo have put their hands and minds to the problem. The result, often enough, is Christ hovering in the sky or shooting cosmic rays out of his head. Even as great an artist as Raphael was flummoxed by the challenge of representing Christ in his aspect of the divine. His Transfiguration turns the episode into a levitation scene seemingly out of a second-rate Broadway musical. Amusing in a kitchy sort of way but otherwise embarrassing as a work of art or theology. Christ was, alas, regularly transformed by Leonardo’s contemporaries into a rather ridiculous Renaissance-era superhero. So much for putting difficult theology into the hands of artists.

In his much-praised recent biography of Leonardo, Walter Isaacson discusses Salvator Mundi. He argues that the most intriguing element of the painting is to be found in the crystal orb that Jesus holds in his left hand. “Leonardo,” Isaacson points out, “failed to paint the distortion that would occur when looking through a solid clear orb at objects that are not touching the orb.” Since Leonardo was engaged in numerous studies of light and refraction, and was generally fascinated with optics, Isaacson reasonably concludes that Leonardo must have specifically chosen to paint the orb “incorrectly.” Isaacson speculates that Leonardo may have done so “because he was subtly trying to impart a miraculous quality to Christ and his orb.”

It’s quite possible that Isaacson is correct in his speculations; we will never know, of course, exactly what was in Leonardo’s mind at the time. But it does seem a rather understated and esoteric expression of Christ’s ‘miraculous’ qualities to suggest that orbs don’t reflect normally in his presence. If Raphael wildly overshot the mark in his Transfiguration, Leonardo (if we follow Isaacson’s interpretation) wildly undershot that same mark. The point of Salvator Mundi, after all, is to show Christ as the Savior of the World, as the very incarnation of God, and therefore, as the author of the laws of the universe. This theological thought is at the heart of Christianity at its boldest: an otherwise normal man is also proposed to be God. Complicated and confusing the doctrine may very well be, but subtle it is not. Leonardo’s painting says it in unmistakable fashion: “Here is a man who is also God.” But if Isaacson is right, then Leonardo’s proof that Jesus is God can be found in the fact that he sometimes goofs around with the way light passes through crystal orbs.

More fruitful as a path toward interpreting Leonardo’s painting is a comparison Isaacson makes between Salvator Mundi and the Mona Lisa. “The misty aura,” Isaacson writes, “and blurred sfumato lines, especially of the lips, produces a psychological mystery and an ambiguous smile that seems to change slightly with each new look. Is there a hint of a smile? Look again. Is Jesus staring at us or into the distance?” If you are not already familiar with it, the wonderful word ‘sfumato’ has become more or less synonymous with the art of Leonardo. It connotes the ‘smokey’ effect produced by the smudging of border lines and the softening of contrasts between colors and tones.

In the Mona Lisa, for instance, the aforementioned “blurred sfumato lines” and “misty aura” give the painting an oft-acknowledged allure. It is largely due to sfumato that Walter Pater was driven to write the following immortal, if slightly breathless lines about Mona Lisa: “She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas, and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants: and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy, and, as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary; and all this has been to her but as the sound of lyres and flutes, and lives only in the delicacy with which it has moulded the changing lineaments, and tinged the eyelids and the hands.”

That’s the greatness of Mona Lisa. But how often do we balance talk about the achievements of this most famous of paintings with observations about its shortcomings? The central failing of Mona Lisa is that it presents mystery simply for the sake of mystery. As Walter Pater also once pointed out about Leonardo’s art, “His problem was the transmutation of ideas into images.” If the Mona Lisa lacks a certain tension that can be found in other of Leonardo’s works, perhaps it is because there is much in the way of deep feeling but no great idea struggling to find physical expression. Google up an image of the Mona Lisa right now and ask yourself a simple question. Why did Leonardo paint this picture? If you’re honest with yourself, the answer has to be that you don’t know. This makes the painting intriguing, of course, but it’s an intrigue accomplished on the cheap, since it relies so much on our ignorance about the circumstances around the portrait.

Salvator Mundi, by contrast, is nothing but tension and great ideas. This is a work that tackles one of painting’s central dilemmas: How do you represent the unrepresentable? How do you make visual that which is beyond the visual? This problem tends to get thorniest when it comes to spiritual matters. And the problem vexes all forms of art, not just the visual. How do you describe in words that which is beyond the limits of language to describe? The Gospel of John resorts to a kind of allusive poetry in order to get its most complicated theological ideas across. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God.” Perhaps we can see Salvator Mundi as Leonardo’s attempt to produce in paint something of what John’s Gospel produces in words.

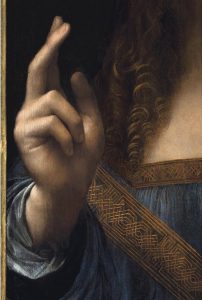

“He was in the world, and the world was made by him, and the world knew him not.” How do you paint that idea? Well, perhaps, at the very least, you show the face of Christ as enveloped in a “misty aura” and “blurred sfumato lines” and with the hint of a smile that is also not a smile. You give it a face that is hard to pin down, that is hard to see at all. You do this because it is a human face that is also and simultaneously the face of God, which cannot be looked upon. And then you put the focus not on the face but on the hand of Jesus, which is simultaneously the hand of God. That hand, the right hand of Jesus coming forth from the painting, emerges from the canvas clear and distinct. The hand is in the gesture of a blessing … but it is the emergence of a fleshy reality out of the indeterminate murk of the indescribably divine.

So, whatever the flaws of the restoration of Salvator Mundi (and I leave that debate to the art historians), whatever the lingering doubts about authenticity (which, again, I leave to the experts), the painting that we now have before us is, I am arguing, more classically a Leonardo painting than the Mona Lisa. There is magic in the painting and there is mystery, just as in the Mona Lisa. But there is also something more. There is a context, the duality of Christ, that puts Leonardo’s painterly skill to a more determinate purpose. This is not sfumato for the sake of sfumato. It’s sfumato at the service of the profound.

Perhaps we can say, then, that with Mona Lisa, Leonardo created a painting as illusive as beauty and the human heart; with Salvator Mundi, Leonardo created a painting as allusive as the Gospel of John. The allusive painting has also proved, often enough, to be quite elusive. It is on its way to Abu Dhabi now. One wonders what further tricks are up its sleeve.