Nicole Eisenman and the Resurrection of Figuration

The contemporary painter Nicole Eisenman tells a rather moving story about winning a MacArthur “genius” grant in the late summer of 2015. She went to a quiet place and wept. Similar experiences have, no doubt, beset many MacArthur recipients. The grant is a crowning glory to an artist’s career, conveying recognition at the highest level along with no small amount of legal tender ($625,000 as of last year). You too would probably cry.

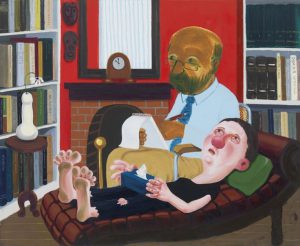

It should also be said that, for Eisenman, the tears were related to art, and to painting in particular. That’s because Eisenman has, for many years now, been making paintings that you wouldn’t necessarily expect to meet the favor of critics, curators, and academics. Since those are the sorts of folk who act as judges at the MacArthur Foundation, it seemed a safe bet that Nicole Eisenman wasn’t going to be in the running. Why is this? Mostly, it is because Eisenman adopts a cartoony painting style and a light, joking attitude on many of her canvases (though by no means all). Take, for instance, a painting called The Session, from 2008.

Stylistically, the painting verges on being a panel from a cartoon strip. A figure resembling Eisenman herself reclines on a couch at her analyst’s office. She has dirty bare feet and a hole in her pants. She clutches desperately at a box of tissues as she weepingly shares tales of woe to her analyst, who jots down notes in a chair nearby. A vase near a bookcase at the left side of the painting is shaped like a phallus. It is a cute and gently self-mocking painting, but not obviously the stuff to put the contemporary art world on notice.

On second glance, however, even a relatively “light” painting like The Session is making a strong argument about what painting can and should be. The painting represents real things in the real world (books, chairs, vases, clocks, etc.). It is figurative (Eisenman likes to paint the human form). It is narrative (the painting shows an experience of misadventures on the analyst’s couch to which plenty of people can relate). Representational, figurative, narrative painting has existed ever since the dawn of painting as an art. But it has been out of critical favor for quite some time now. Only recently has the tide begun to turn. So, the story of Eisenman’s success is tied to a larger story. That story is the journey of painting over the last hundred and fifty years.

The Challenge of Photography

To talk about Nicole Eisenman in 2016, then, it helps to go back to the year 1829. We are in France. We are looking over the shoulders of two Frenchmen, one by the name of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, and the other by the name of Nicéphore Niépce. The two men were messing around with silver plates, nitric acid, halogen fumes, and mercury, among other substances and could easily have been confused for medieval alchemists. In fact, they were trying to figure out how to capture images projected through a lens. The result of this process would come to be known as the daguerreotype. (If Niépce hadn’t died suddenly of a stroke in 1833, it might have been known—even less euphonically—as the niépcotype.) The era of modern photography had begun.

Artists had been using mirrors, lenses, camera obscuras, and other devices for projecting images onto canvas (which they used as painting aids) for ages—back at least to the 16th century, if not earlier. The “realism” of paintings by artists like Caravaggio, Vermeer, Canaletto, and Reynolds is due, at least in part, to such devices. But the daguerreotype brought something quite new to the table. With the daguerreotype, the hand of the artist could be removed completely from the process of creating images. By clicking a button, images could be transferred from a lens directly onto a metal plate (photographic paper would come later). These images were convincing, true-to-life, and stunningly accurate in terms of detail and single-point perspective. More than that, they were beautiful. The images were like magic.

There are a few wonderful examples of early daguerreotypes reproduced in this article by Alan Taylor at The Atlantic. I draw your attention to image #4, taken by Mathew Brady sometime between 1851 and 1860. It is a portrait of an unidentified young woman. Though we do not know her name, the daguerreotype captures the woman in such stark “thereness” that the heart skips a beat. Glancing at the picture, the nameless and long-dead woman is suddenly present. How can this be? A quote from Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida comes to mind. “The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being, as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star.” No painting, however realistic, seems quite able to do that.

Image: Atlantic Magazine

Once people started to look at those first daguerreotype plates, painting could never be the same.

The daguerreotype (and Fox Talbot’s similar process, invented around the same time in England) plunged painting into a crisis of confidence from which it is still, nearly two hundred years later, trying to recover. You have to feel a little sad for the painters of the early 19th century. Here they were, heirs to a tradition that had been perfecting its realist techniques for centuries. Painters had mastered the ability to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. They’d worked out the mathematics of linear perspective. They’d played with oils and varnishes, brushes and canvases to the point where looking at a painting created by a competent painter was like looking through a window and seeing an exact replica of the real world on the other side. Then, with the splash of a few chemicals on a metal plate, all this technique was rendered moot.

Painters who decided to persevere even after the advent of the daguerreotype were thus forced to do quite a bit of soul searching. They had a corpse to revive. They asked themselves: Is there anything about the painted image that is vital and irreducible, that cannot be replaced by photography? The answer seemed to be yes. Paul Cézanne, for example, once said, “Painting from nature is not copying the object; it is realizing one’s sensations.” That’s to say, painters in the mid to late 19th century began to realize that painting could address not “what we see in the world” in some mirror-like objective sense of the term, but “what it’s like to see in the world.” This shift opened up the possibility of Impressionism, the more radical Post-Impressionist movements, and all the 20th century experiments in non-representational art that followed.

First Responses

By the early decades of the 20th century, many painters had begun to focus less on what’s “out there” in the world and more on what is often called “pictorial space.” They painted geometric shapes and experimented with color and surface. Or they tried to paint the unseen—the numinous aura of things, the wisp of the transcendental that hovers in an objectless netherworld. Or they painted paintings that were “about” painting. They raised and then “solved” formal problems about surface and about edges and marks. Or, to give just one more example, they indulged in the expressive freedom, the liberating activity, of slapping colored pigments onto a flat surface. They reveled in the sensuousness of painting. And so it went, decade after decade.

Painters explored, beautifully and often with incredible results, the non-representational dimensions of the painterly art. But had they really escaped their ‘near death’ experience with photography? Ever so persistently, a question continued to gnaw at the edges of the painterly mind. The question was this: “Is it safe to come back to the real world yet?” Put another way, many painters wondered whether painting had learned enough about its true soul and nature to take on aspects of the representational that had been ceded to photography and then film.

It’s worth noting, then, that when Nicole Eisenman won her MacArthur “Genius Grant” last year, the committee specifically addressed the centuries long history of painting and its retreat from representational and figurative work. Eisenman was praised for having “restored to the representation of the human form a cultural significance that had waned during the ascendancy of abstraction in the 20th century.” With this success, she and other figurative contemporary painters over the last decade have opened the representational door in earnest. Of course, there were, we should note, plenty of painters still painting the human form during the 20th century. Plenty of these painters were major figures. Picasso painted people throughout his career. Francis Bacon did as well. Frida Kahlo. But then again, the importance of Picasso’s work has largely to do with the ways he broke down, deconstructed, and reimagined the human form. Bacon reduced the human body to a meat machine. Kahlo poked around the human body looking for symbolic messages. Rarely was figurative painting taken up for the sheer love of figuration and without ulterior motive.

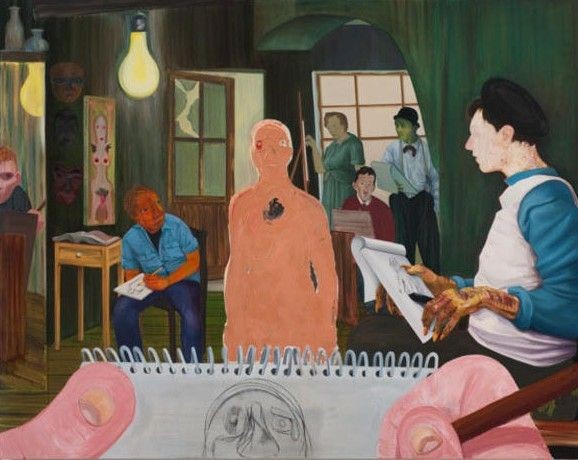

Nicole Eisenman, by contrast, isn’t deconstructing the human form. She is perfectly happy to paint scenes showing people doing real things in the real world (cartoony style notwithstanding). She paints the human body without ulterior motives. She doesn’t look at the history of painting as something to reject or overcome. Quite the opposite. She’ll paint in a style that is reminiscent of German Expressionism one day and of, say, Botticelli the next. Eisenman seems comfortable with all the ways that past artists have sought to render likenesses of the real world. That she does so with wit and sophistication and with an edgy lefty politics (her work has been described as “deeply lesbian,” a point that Eisenman accepts while, at the same time, keeping her distance from) helps the figurative pill go down for those who like to think of their artists as “radicals.”

“I’m Really Into Narrative”

But the significance of Eisenman’s work isn’t just that she’s an unashamed figurative painter. What she does with those figures is key. Often, she puts her figures in relationship to one another within social space. That’s to say, Eisenman isn’t just a figurative painter, she’s a narrative painter. Can a painting tell an honest-to-goodness story? This possibility was thought to have been abandoned with the demise, in the 19th century, of the “historical painters” (painters who recreated notable scenes in history, like Socrates drinking from his poison cup). Even if a painting can tell stories, don’t we now have other, better forms of visual art for telling stories—films, most notably, but also comic books and graphic novels?

In a conversation between Nicole Eisenman and painter David Humphrey, published in BOMB Magazine (Summer 2015), Eisenman said the following about her work: “My thing is that I’m really into narrative. It’s not about the figure—it’s the storytelling that I’m stuck on. The meat and bones in my practice is somewhere between texture and storytelling.” A little bit later in the conversation, she said, “I want stories that happen outside of the self, outside of art practice.”

This may not sound like the most audacious of statements. Put her words in the context of art history, however, and it’s pretty damn bold. That’s because of the “Why” questions. Why painting? Didn’t photography and then film already steal this job from the painters? Most of all, why force a static medium, one that cannot account for the dimension of time, into the role of conveying narrative?

For Eisenman, there seems to be something that painting can do with narrative that no other art form can replicate. In thinking this through, let’s admit one thing right off the bat. Painting is a terrible medium for telling a straight, linear narrative. If you want to tell a story in time (this happened, then this happened, then this happened, etc.), you are better off choosing almost any other medium.

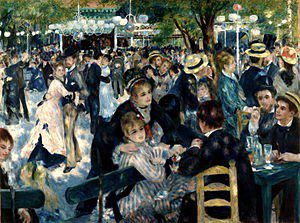

What, then, is the special relationship between painting and narrative? Let’s go back in time again to search for a possible answer. We’ve returned to France, to Montmartre, the famous neighborhood on the north side of Paris. It is a Sunday afternoon in 1876 and people are gathered at an outdoor café known as the Moulin de la Galette. A painter is present. His name is Pierre-Auguste Renoir. He is in the process of painting one of the most recognizable paintings of the last two hundred years. It’s an Impressionist masterpiece, what with the dappled light and the swirling figures, the bright colors, the sense of life caught in the moment of its unfolding.

This painting is a masterpiece of narrative because it holds within its frame so many stories. The stories don’t proceed from left to right. They don’t emerge as a plot progressing through time. Instead, the stories have to be picked out from the chaos of social life. There is the story of youthful flirtation as two young girls turn their attentions toward a fellow (we see him from the back) at the foreground of the painting. There is a story of stress and strife in the far-left background of the painting. A woman sits on a bench as her male companion desperately attempts to address whatever wrong has been committed. There are stories in the couples dancing, each couple nuzzled together in their respective cocoons of physical embrace. There is also a story of individual isolation within the crowd: a boy’s face staring out from the canvas in his lonely distress; a young man smoking a pipe, lost in the interiority of his own mind.

Finally, there is a more general story. This is a story of Parisian life at a specific moment in history. It is a story of people trying to take their pleasure as they can. There is a melancholy aspect to this pleasure. That’s because Paris, and the neighborhood of Montmartre in particular, was emerging from the battles of the Paris Commune, which happened just five years before this painting was made. Hundreds of locals in armed revolt were executed by firing squads not far from the Moulin de la Galette. The presence of life and gaiety in Renoir’s picture is thus made more poignant by the implied absence of those who so recently died.

A photograph has great difficulty packing in this many narratives for the simple reason that a photograph tells the literal truth of the moment, right there on the surface. A photograph says “this is how it looks at the Moulin de la Galette right now.” The immediacy of the photograph is what astounds. Renoir’s painting, by contrast, is full of artifice. The painter has the luxury of combining moments, taking one scene from earlier in the day and combining it with another from later, or adding elements that never happened at all. Renoir wants to multiply narratives, both across the surface of the canvas and in the historical sense.

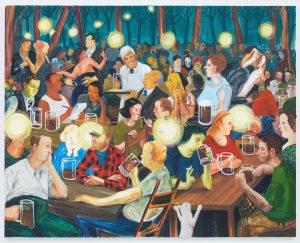

In 2008, Nicole Eisenman painted her own version of Renoir’s Bal du moulin de la Galette. It’s called Brooklyn Biergarten II. Eisenman’s painting is quite consciously modeled after Renoir’s picture. The glowing bulbs of incandescence from the string lighting in Eisenman’s painting reference the hanging lamps and the bursts of sunlight in the Renoir. Figures are grouped similarly, with dancers to the middle-left of both paintings and flirting couples in the foreground. As in Renoir’s painting, the social gathering in Brooklyn Biergarten II sets the scene for dozens of individual stories.

In the aforementioned BOMB Magazine discussion, David Humphrey makes an insightful comment about Eisenman’s work. “Something we share,” Humphrey notes of Eisenman, “but that you really dig into, has to do with the relationship between individuals and groups. The psychological space between people is like the space between a painting and a spectator, but then you expand that space to constitute collectives, tribes. Sometimes they’re waiting for the subway, as in that painting over there (points to a work), or they’re at a biergarten, or hanging out around the privacy of a table. This is a really interesting subject that doesn’t get a lot of play in contemporary art—the resonance of an individual person within the pack.” As a painter, Eisenman is in complete control of the social scene that she depicts. This allows her to achieve a density of narrative that a photographer might have to wait a lifetime to see and faithfully record.

This also gets to the crux of how a single painting can be narrative without needing to show the development of a story through time. There is no development. Instead, there are many interactions going on all at once. In a painting, you get to study those interactions for as long as you like. The interactions get richer in the studying. You can toggle back and forth, as it were, between looking at the individual actors in the scene and looking at the group dynamics.

Part of the lure of Renoir’s famous painting is how it makes visible that peculiar phenomenon, so endemic to modern life, of loneliness within a group. It also explores the sense in which it is only in a crowd that individual human beings can find the freedom to be themselves. These are contrary forces. But urban life is what it is because of the constant interplay between these two forces. The power of Renoir’s painting comes from the fact that both forces are right there on the canvas. You can feel the simultaneous punch of loneliness and freedom, togetherness and alienation, as your eye drifts around the scene.

The same is true of Eisenman’s take on Renoir in the Brooklyn biergarten. Are the three men hefting beer steins at the foreground of the painting sharing an experience or not? It is hard to say. They are sitting together. They are even, perhaps, in the midst of a conversation. Or maybe they are simply thrown together at the same table with little to say. The indeterminacy is part of the point. Eisenman’s picture, like Renoir’s before it, is neither, exactly, a critique of contemporary life nor, exactly, a celebration of it. Think of it, rather, as a study; a study of a social group by means of its individual stories and by Eisenman’s painterly skill in highlighting those stories. This was something that the MacArthur judges specifically cited in Eisenman’s work, noting that, “Eisenman’s skill as a painter of imaginative compositions is evidenced not only through the array of social types represented but also through the bold contrasts of color that inject the work with emotional and psychological intensity.”

The beauty of a painting, as opposed to a photograph, is that you can put anything onto the canvas as long as helps fill out the narrative. Eisenman makes full use of this freedom. Look again at the Biergarten image above. There is a skull, a death’s head, staring out at us from the top-right center of the scene. It is a startling moment when you’re gazing unaware at Eisenman’s painting and then finally notice the skull.

I think the death’s head plays the same role as the little boy’s disturbed face staring out in Renoir’s earlier picture. Social gatherings are places of pleasure, frolicking, sexual tension, animated discussion, alienation, and solidarity. But doesn’t all this intermingling always carry with it a distinct, if unnamable, sense of unease? This unease, commingled with desire and the compulsion to find ourselves in others, has been a characteristic of city life for a long time now. Indeed, the unease has been with human kind for much longer than that. Call it the affliction of self-consciousness. The dread of being trapped inside one’s own head, cursed to play out the drama of being this specific person, day after day, year after year, knowing, with the terror that flashes up now and again, that this specific consciousness we’re each doomed to perform is but a fleeting thing. It dies. It vanishes into nothing. We seek out social gatherings partly so that we might lose ourselves, for however long, within them. But this only works for so long. Eisenman’s death’s head is a reminder that we can never escape the dilemma of the self entirely.

That’s a deep story, a story that goes back tens, maybe hundreds of thousands of years. It started when a specific species, homo sapiens, became aware of itself and developed cultural tools—language, art, rituals—in order to express that awareness. Nicole Eisenman paints canvases that have room for such deep stories alongside the stories that skim across the surface—stories about a boy trying to talk to a girl or about a lonely old woman taking another drink or a couple engaged in a dance. One of the strengths of the medium of painting, Eisenman has reminded us, is that it can hold all these different strands and layers of narrative together all at once.

The great painters of old discovered this fact long ago, artists like Peter Paul Rubens, with his giant canvases packed full of human bodies in complicated, many-layered levels of interaction. These lessons were set aside when painting, traumatized by photography, engaged in a non-representational journey of self-discovery that lasted for much of the last century. Today, the paintings of Nicole Eisenman serve notice; figurative painting with a narrative thrust is back in earnest. The curse of Daguerre, finally, has been lifted.