Jeff Koons: Or, Who’s Liberating Whom?

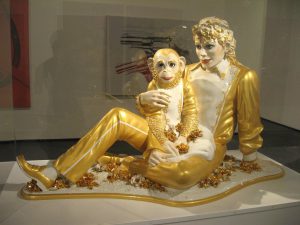

In 1988, Jeff Koons created the work of art known as Michael Jackson and Bubbles. It’s a life-sized porcelain sculpture–actually the largest handmade porcelain sculpture ever made. It depicts Michael Jackson leaning back on a field of flowers as he cradles his famous chimpanzee. Both the monkey and the man are clad in golden outfits. The sculpture is extremely shiny.

Michael Jackson and Bubbles is part of a series of sculptures known, collectively, as the Banality series. The series includes a sculpture depicting a topless Jayne Mansfield holding a stuffed Pink Panther (Pink Panther) and another life-sized porcelain sculpture depicting a smiling brown bear in a T-shirt hugging a policeman (Bear and Policeman).

Koons has his defenders, but with works like Pink Panther and Michael Jackson and Bubbles, he has driven many in the art-critical establishment into what can only be called paroxysms of outrage. Jeff Koons’ recent retrospective at the Whitney Museum (2014) was another chance for the critics and academics to take their whacks. Jed Perl, in a piece for the New York Review of Books, summed up the feelings of many. Perl titled his piece, “The Cult of Jeff Koons.” Here’s the opening paragraph:

“Imagine the Jeff Koons retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art as the perfect storm. And at the center of the perfect storm there is a perfect vacuum. The storm is everything going on around Jeff Koons: the multimillion-dollar auction prices, the blue chip dealers, the hyperbolic claims of the critics, the adulation and the controversy and the public that quite naturally wants to know what all the fuss is about. The vacuum is the work itself, displayed on five of the six floors of the Whitney, a succession of pop culture trophies so emotionally dead that museumgoers appear a little dazed as they dutifully take out their iPhones and produce their selfies.”

“You Can’t Like This”

If Jed Perl is right (and he may well be) the only thing that is really interesting about Jeff Koons is the magnitude of the boondoggle. The question is how we square Perl’s contempt with, for instance, the following claim to be found at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s website: “Jeff Koons is widely regarded as one of the most important, influential, popular, and controversial artists of the postwar era.” There are, moreover, a number of important critics who have held this view, the best and most intelligent being philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto.

Arthur Danto wrote a piece about Koons in 2004 titled “Banality and Celebration: The Art of Jeff Koons.” Here’s how Danto described the sorts of objects and experiences that inspired Koons in his work:

“Cute figurines in thruway gift shops; the plaster trophies one wins for knocking bottles over in street carnivals; marzipan mice; the dwarves and reindeer that appear at Christmastime on suburban malls or the créche before firehouses in Patchogue and Mastic; bath toys; porcelain or plastic saints; what goes in Easter baskets; ornaments in fish bowls; comic heads attached to bottle stoppers in home bars.”

Koons, Danto claimed, takes up this common imagery of middle-class (and middle-brow) America for a purpose. That purpose is to be the great defender, even the great liberator, of everyday taste. Whatever you like, Koons is telling us, is okay. Walking into a highbrow place of culture like an art museum or a gallery can be an intimidating affair, especially for the uninitiated. But Koons fills those highbrow spaces with artwork that would, for the most part, look at home in the aisles of Walmart. Koons’ work therefore seems to carry with it the following whispered words of encouragement: “Don’t be ashamed that you take comfort and joy in these everyday objects and images.” With Koons, we are liberated from the shame we might normally feel in liking the kitsch we are otherwise told is deplorable. According to Arthur Danto, Koons’ works, “portray, as if from within, the sensibility of the lumpen middle class, and Koons showed himself to be the Cellini to this taste. The art world wants to say to Koons, You can’t like this! To which Koons must reply, I can and I do. And so, in your heart of hearts, do you.”

And thus the battle is enjoined. On one side, Koons and his vast army of middle brows who want to like what they like. On the other, the critics and intellectuals who aren’t inclined to like anything unless it is difficult and unlikeable. Sometimes, amusingly, critics and intellectuals attempt to recruit Koons to their own position. An example of this phenomenon is captured in the following quote by the illustrious Robert Storr, former Dean of the Yale School of Art. “[Koons’] mating of Jayne Mansfield and the eponymous cartoon character in Pink Panther is a thoroughly enjoyable send-up of heterosexual rapture and celebrity romance.”

But if Danto is right-and if Koons can be believed-the sculpture is not a send-up at all. Koons is being thoroughly sincere. Koons’ point in the work is that we ought to get over our shame and acknowledge two simple truths: A) that Jayne Mansfield is sexy and, B) that the image of Jayne Mansfield cuddling a pink toy is erotically satisfying (Koons has likened the pink stuffed animal in the sculpture to a sex toy). Robert Storr can only appreciate the work by seeing it as a critique of heterosexual rapture and celebrity culture. What Storr cannot see is that the person Koons wants to liberate is Robert Storr, or anyone else who cannot allow him or herself to enjoy Pink Panther exactly for what it is: a kitschy erotic thrill. Pink Panther is, in short, a celebration of the very things Storr thinks Koons is “sending-up.”

According to Arthur Danto, the imperative of all Koons’ work is the following: “Be yourself and don’t pretend to be someone else whom you believe superior to yourself. Your tastes are all right as they are.” Arthur Danto quotes Koons’ own explanation of the works he created for the Banality series: “I was telling the bourgeois to embrace the thing that it likes, the things it responds to: For example, when you were a young child and you went to your grandmother’s place and she had this little knickknack, that’s inside you, and that’s part of you. … Don’t divorce yourself from your true being, embrace it.”

The dilemma for so many of the critics and interpreters of Koons’ work, even those who think they are sympathetic to Koons, is that they don’t want to do what Koons asks of them. They don’t want to embrace what he calls their “true being.” And the critics are not crazy to resist Koons, since his art demands that we surrender our critical distance. You could even say that Koons’ work is a radical attack on the very idea of criticism in the first place. To approach Pink Panther the way Koons wants us to approach it would be simply to shut up and give in to the pleasure.

The anger toward the art of Jeff Koons is therefore the anger of people (critics and intellectuals, mostly) who feel themselves, not unreasonably, to be under assault.

That Arthur Danto taught himself more or less to like and celebrate the work of Jeff Koons is a testament to the degree to which he took seriously the task of transforming the work of the critic in a post-critical age. Danto believed that in an age of pluralism, the critic no longer puts forth an agenda for art, nor tries to establish a criterion for making judgments about works of art. Instead, a critic tries to take each work seriously on its own terms, to understand it from within. That’s what Danto tried to do with Koons.

The question, them, is whether the art of Jeff Koons genuinely liberates us from our shame and allows us to like what we really want to like. Can we, along with Danto, view Koons’ work as an utterly sincere celebration of shiny things and alluring objects?

There’s Something Wrong Here

The immediate problem in doing so is that the experience of looking at the art of Jeff Koons is never quite the uncomplicated pleasure Koons, and Danto, promise. The artwork is weird, even disturbing (as, we might note, is the man himself). Even an otherwise innocuous work like Bear and Policeman is simply and undeniably creepy. Maybe the creepiness, in this case, comes from the size (it is life-sized). And why, exactly, is the giant bear hugging the rapturous policeman? What’s really going on here? If this is supposed to be fun and liberating, it ends up being ominous and discomfiting. That’s to say, the liberation that we are supposed to achieve from enjoying Koons’ work ends up fizzling out somewhere after the first glance. From certain angles, the look on Jayne Mansfield’s face in Pink Panther strikes me as a look of fear. Her centerfold smile doesn’t hold up. There is something wrong here.

There is an utterly unforgettable scene in an episode of Robert Hughes’ television documentary “The New Shock of the New,” where Hughes and Koons discuss Koons’ sculpture Woman in Tub.

The porcelain sculpture (also part of the Banality series) shows a naked woman in a bathtub holding her breasts in her hands, shocked at the appearance of a snorkeler beneath her. The sculpture, Koons carefully explains to Hughes, tells us something about the shame children feel around masturbation. Hughes, playing along, encourages Koons to say more. Well, Koons tells Hughes, the sculpture is also about how the woman is being victimized and about how we, as the viewers, want to victimize the woman too. Hughes takes this comment more or less in stride as he strokes the right leg of the woman in the tub.

Clearly, with Woman in Tub, we’ve passed beyond simple pleasures. We’ve moved into the realm of something dark, creepy, and unpleasant. An important question is whether Koons fully realizes that he has taken us into this territory. Having looked at much art and read many interviews by Jeff Koons over several decades, I don’t think he does. In this sense, Danto is correct. Koons is fully committed to the view that his art liberates us from our bad, shame-driven, critical selves and opens us up to the simple pleasures all around us. Since Danto takes Koons seriously in this regard, he is not very comfortable with the dark and creepy aspect of Koons’ art. He senses that the uncanniness of Koons doesn’t sit well with the artists’ promise of liberation. About this aspect of Koons’ work, Danto opined, “I feel he has lost touch with the surface of ordinary life, which his concept of morality presupposes.”

But that’s the very thing with Koons. His work always loses touch with the “surface of ordinary life.” One even begins to suspect that Koons has stumbled, unintentionally, upon a deep metaphysical truth here. That’s to say, every time you try to stick to the surface of ordinary life, something deeper, and potentially more disturbing, manages to get in the way.

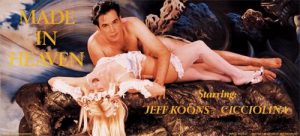

This tension between Koons’ love of surface and his (unconscious) fascination with something darker is to be found in almost every work of art he’s created. The darkness permeates his personal life as well; and Koons’ has frequently merged his private life and his art. Back in the 1980s, for instance, Koons became obsessed with the Italian porn actress (and part-time politician) Cicciolina (Ilona Staller). Koons based some of the images of the Banality series on pictures of Cicciolina he’d found in magazines. He went so far as to track her down in person. They married in 1991. Koons and Cicciolina made artwork together, including a series of giant photographs under the title Made in Heaven that graphically depict the couple in various sexual acts. Large sculptures of Koons and Cicciolina coupling were also produced.

Koons and Cicciolina had a son and then, a few years later, divorced. The divorce was painful and acrimonious, featuring a drawn-out custody battle over their son (which Koons lost).

During testimony, Cicciolina described a miserable marriage in which Koons paid her no attention and spent most of his time watching “videos.” Koons, for his part, has described the great suffering caused by being separated from his son.

The point here is that the joyful celebration of unencumbered sexuality that was Koons’ and Cicciolina’s marriage turned out to be the opposite. You could call this highly unsurprising, but it seems to have come as a great shock to Koons himself. Cicciolina has, we might note, described her own sexual awakening as coming about when she worked at a hotel in Hungary (she is originally Hungarian). According to her, the Hungarian secret police asked her to seduce foreign guests and then take pictures of whatever documents they might be carrying. So let’s just say there are complications here that take us far beyond the territory of unencumbered pleasures and bourgeois liberation. Whatever Koons thought he was getting with his perfect porn star, it turned out there was a fully complex (and troubled) human being under the gloss. Examining Koons’ marriage is therefore a bit like looking at Pink Panther and suddenly noticing the (unintended?) fear in Jayne Mansfield’s smile. Every time Koons reaches for liberation, his hands grasp something else entirely.

These sorts of unintentional complications pop up everywhere in Koons’ life and art. And yet Koons himself seems strangely unaware of (or indifferent to) the jarring disjunctions within the work he creates. In interviews, the contradictions between intention and reality are manifested physically. Koons comes off as a nervous and repressed person explaining to us, in complete earnestness, how he has triumphed over nervousness and repression. Many of his explanations of his own art simply make no sense. Here are a couple of things Koons has said about the Made in Heaven series in an interview at The Guardian:

“When I made it, I was just thinking about the ideas around me, I was involved with banal images. I realized that people respond to banal things; they don’t accept their own history; not participating in acceptance within their own being. I started then to take that into the body. Where do people start to feel guilt and shame and rejection of the self? … I think of Boucher, domesticated, un-domesticated. I think of all the polarities of the baroque and the rococo…My ex-wife and I were standing in there as Everyman and Everywoman. I wanted to present this Jungian, Dionysian way of looking.”

But wait – the message of Jungian analysis is that we are inherently complicated creatures, that we cannot simply, as Koons would have it, “accept” our bodies or easily get rid of guilt and shame. Here, for instance, is a typical quote from Carl Jung: “Knowing your own darkness is the best method for dealing with the darknesses of other people.” This is something like the direct opposite of what Danto calls the Koons “morality,” which denies that there is really such a thing as darkness in the first place! That’s to say, Koons’ work denies darkness and depth while simultaneously ushering it in. For all the shininess, for all the supposedly uncomplicated enjoyment that Koons’ work is meant to deliver, it is difficult to be in a room with his art without feeling an overriding sense of unease.

Koons therefore makes art (seemingly despite himself) that reveals the troubles lurking just beneath the surfaces we are never meant to penetrate. Or are we? That’s the trouble and the excitement of Koons’ work. It is all so much fun! But wait, why I am not having any fun? Was it really meant to be such fun in the first place?

Interestingly, the work wouldn’t be so weird, so troubling, and so uncanny without its surface sheen of naive sincerity, without its bland insistence that our desires would be simple and uncomplicated if we just gave in to them. Everything that is compelling, everything that is, frankly, hateful in Koons’ work hinges on that attitude, an attitude Koons inherited from the late phase of Andy Warhol, and that he has taken as far, maybe, as it can go.

The more you look at the art of Koons, the more you feel a creeping sense of discomfort, the more Danto’s defense falls apart. If the work of Jeff Koons is worthy of being called “important art” it’s not because it cures us of our shame, it’s because it forces us to confront that shame and to stew in it. This is also why Jed Perl’s blanket dismissal of Koons is just as unsatisfying as Danto’s blanket acceptance. To dismiss Koons as completely vapid means taking the vapidness of his art at face value. But that’s exactly what it is impossible to do in looking at, for instance, Bear and Policeman. A sculpture that strange cannot, by definition, be called vapid. It’s very strangeness forces us to take it more seriously.

So, perhaps there is another argument to be made for the importance of Jeff Koons. It is to argue that he makes troubling art for troubling times. To put it more precisely, Koons makes artwork that takes up the specific troubles of our times, the specific dilemmas of a commodity culture utterly obsessed with surface, utterly committed to the metaphysical claim that all depth is an illusion. He makes work that is like a test case for this thesis. Koons himself does not understand this aspect of his work. But in the end, it doesn’t matter what he thinks. His work is a death struggle between surface and depth, a duel between claims of happy liberation and the persistence of darkness and the uncanny.

To defend or to attack Koons’ for what he claims his art to be is therefore beside the point. The art of Jeff Koons is both utterly indefensible and utterly compelling. Koons’ total embrace of emptiness creates work that is accidently profound, precisely because of all its internal contradictions. Koons’ work, no matter how hard he tries, always ends up being deeper than he wants it to be. The surfaces can’t hold the darkness at bay. And for that, we are surprisingly grateful.