For love or money? The merits of investing in art

In November 2017, in a packed auction room in New York, da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi sold for $US450m. That spectacular transaction says many things about our age. One of them, surely, is that at that moment the idea of art as an asset went mainstream. You don’t pay $US450m for wall decoration.

Over the last decade or so, supporters of the art market have been arguing that art should be viewed as an asset. Are they right? An asset is simply a “store of value”, something that can be purchased today and will hold value over time. Art undoubtedly satisfies that definition.

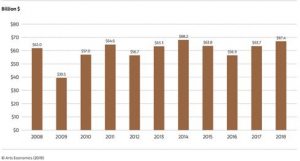

Art’s credentials as an asset have strengthened greatly with the growth of the market. Global art sales were $US10bn in 1990. Last year, according to the 2019 Art Basel UBS Art Market report, released a few weeks ago, the market topped $US67bn.

Galleries account for just over half the market – $37bn in sales with auctions comprising $29bn. The US is easily the biggest market, with Britain second and China a close third. In something of a lengthy digression, the report investigates gender discrimination in art. It reveals that artworks by women sell, on average, for a whopping 38% less than works by men.

Amidst the hoopla about the market’s size, few have paid attention to flatter growth since 2008. As seen in the chart above, this decade has seen sales grow by only 9%, not even keeping pace with inflation. Art Basel break this down by the price bracket of the works sold. The “low” end ($50k and below) accounts for the vast bulk of transactions but prices in many cases have fallen. Mid-market sales ($50k up to $1m) cover just over a quarter of transaction. These works have held their value over the last decade. Works valued at over $US1m – less than 1% by volume of sales but over 60% of sales by value – appear to have enjoyed price growth stronger than artworks at lower price points.

It’s not possible to infer from this data to the likely price movement of individual artworks – they are just average market trends. Just as uncertain is the relationship of the art market to other asset markets. Were we considering stocks or bonds, the relationship to interest rates, economic activity and so on would be deeply analysed. In the case of art these relationships remain little understood.

Let’s not blame the Art Basel report – it is actually a high-quality effort. The problem is that the art market diverges from the ideal efficient market in just about every possible way. There is no “standard” art work, transactions are difficult and costly, and market information is chronically poor. It’s about as opaque a market as you can find.

Looking at this market through the eyes of an investor, what can art offer? Like, say, real estate, it boasts strong capital gains over the longer term. Of the 600% growth in turnover since 1990, price escalation has been a major contributor, albeit skewed toward higher priced works. Advocates say that returns on art investments are uncorrelated with the returns from other asset classes, making it attractive for inclusion in a diversified portfolio. Art is both durable and highly mobile. Various airports in Europe and elsewhere host tax free storage zones where valuable artworks can be held. If a painting quietly changes hands and moves from one storage suite to another, who is to know? Individuals unhappy with their tax bills or nervous about their spouse’s divorce lawyers have been known to exploit these characteristics to great effect. And, of course, art emphatically offers aesthetic returns – it looks great on the living room walls while you await the capital gains.

But art has an Achilles heel – it is difficult to buy and sell. Identifying reputable current artists, knowing what a “fair” price is and who might pay it, understanding a work’s provenance, the risk of forgery, the list goes on and on.

Transaction problems are often referred to as “information asymmetries” – a few people know a great deal and lots of people don’t know very much. Little wonder that the market relies so heavily on intermediaries like galleries and auction houses. Intermediary services come at a cost, one that broadly reflects their contribution to “market making”. As you would expect, the higher the risk the higher the fees.

These intermediaries warrant a closer look. The business of most local galleries is selling new work by their roster of artists – this is the so-called “primary market”. The primary market bears the highest risks in the art market because it deals with artists who may not have a strong market for their work. To compensate for this risk, these galleries charge high margins – commonly 50% and sometimes more. In some industries a 50% margin is the stuff of dreams – and indeed galleries are sometimes criticized for taking money out of the hands of needy artists.

For the most part, this criticism is misplaced. Not only do galleries provide nice premises for displaying art and develop a network of potential buyers but they also provide artists (especially emerging artists) with lots of ancillary support. This is costly and risky – not every artist finds a market for their work. One famous example is the London based dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who supported the Impressionists. He eventually became wealthy from selling their art, but only after 20 years of financial peril supporting those artists in the face of almost non-existent demand. Press coverage of the struggles of small galleries suggests that even a 50% margin may not provide adequate compensation for these kinds of risks.

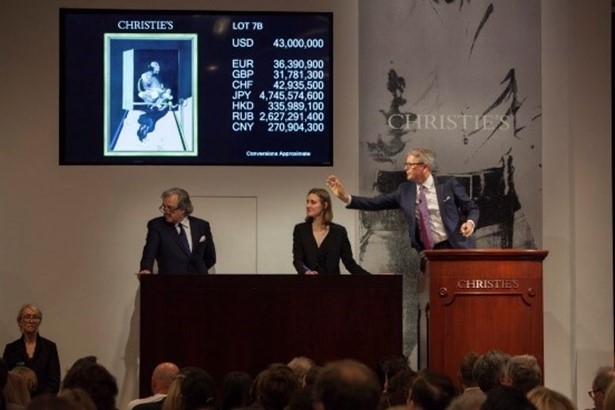

Another important group of intermediaries is auction houses that handle nationally known artists. They charge a “buyer’s premium” of around 22% (but negotiable) on works they sell. Dealing in known artists is less risky than creating a market so margins in this “secondary market” are lower than for galleries.

Most prominent of all art intermediaries are the global auction houses that sell globally recognized artists. Christie’s and Sotheby’s are the biggest, between them accounting for 40% of the entire global auction market. For a work valued at, say, $US1m the buyer’s premium would be around 14%. This is less than nationally focused auction houses but still yields a hefty commission for works valued in the millions.

Essential though these intermediaries are, their fees eat into art investment returns. It’s not encouraging to buy some carefully chosen art, only to see hard-won gains being swallowed up by transaction fees. Having said that, these intermediaries collectively offer a comprehensive menu of risk-reward combinations to art buyers. Unknown, higher risk artists are typically priced lower, increasing the prospect of strong returns. Well-known artists sell for much higher prices, meaning lower but less risky expected returns. The market knows how to price risk.

The Art Basel report estimates that about 40m items sold at auction in 2018. That makes the market sound more liquid than it really is. In 2008 – 9 sales declined by a huge 40% as supply contracted in response to the global financial crisis. (It recovered thereafter.) A lack of liquidity can sometimes impact a specific area. European Old Masters seems to be a current example. Turnover in this market segment has been declining steadily and in 2018 reached its lowest level in 10 years.

Asset markets like art also sometimes surprise on the upside. The economist Robert Shiller won a Nobel Prize for his work on asset markets and, in particular, the idea of “irrational exuberance”. He argues that price spikes can be expected in markets like real estate (and art) when sensible investors are confronted with poor information and shifting psychology among other investors.

One way to think about Schiller’s argument is that asset markets like art are prone to making price “mistakes”. Prices at auction are, of course, correct at the moment the gavel falls. If those price levels hold up, fine. But if prices are not maintained in later trading, perhaps a mistake has occurred. Perhaps Salvator Mundi was a mistake in the sense that it was a price spike, an expression of exuberance that is followed by buyers regret. Price mistakes can also appear in the form of bargains. Perhaps low prices for art by women artists are a mistake. The New York Times recently noted the frequency with which price records are being set for female artists. Price overshoots and undershoots usually get corrected but as to when – sadly, that is unknowable.

The hard-nosed conclusion is that art is an asset, but an inefficient asset. It doesn’t offer what we value in financial assets – a regular income stream, a known risk profile, market liquidity. Investors, if rational, should favour financial assets. It’s just that they don’t look nearly so pretty on your walls.